From the Summer 2015 Artforum.(This version is slightly different.) — J.R.

Doctor (off): Has this happened to you before?

Ventura: It will happen again, yes it will.

Trying to rationalize Pedro Costa’s Horse Money in terms of a synopsis is ultimately a fool’s game, but connecting it to recent Portuguese history is a necessity. The April 25, 1974 military coup known today as the Carnation Revolution, led by the leftwing MFA and ending the Estado Novo dictatorship that lasted almost half a century, took place when Costa was in his early teens. Ventura, Costa’s slightly older principal protagonist in practically all of his other recent films — a Cape Verdean immigrant and construction worker, always playing himself and scripting his own dialogue — was around in Lisbon too. But as Costa told Mark Peranson in an interview in Cinema Scope, Ventura’s experience of the same events was radically different:

I was very lucky to have been a young man in a revolution, really lucky….And I was discovering a lot of things, music and politics and film and girls, everything at the same time, and I was happy and anarchist and shouting in the streets and occupying factories and things like that — I was 13 so I was a bit blind. It took me 30 years to discover that Ventura had been at the same place, at the same time, crying, very afraid, of what I was doing, and what the soldiers were trying to do. So this is an interesting thing. I was shouting the slogans, the common revolutionary words with the banners and the stuff, and he was hiding in the bushes with his comrades, the black immigrants, that had started coming in 1968 from all the Portuguese ex-colonies.

Even for a filmmaker as radically transgressive as Costa, Horse Money represents a sharp departure from the long takes of In Vanda’s Room (2000) and Colossal Youth (2006) in its privileging of traumatic memory and consciousness and all the narrative fragmentation this entails over any sustained continuity of space or chronology. Speaking to a packed film festival audience in Hong Kong that I was part of last spring, Costa further noted that in all the photographic records that he’s seen of the Carnation Revolution, the roughly 100,000 black immigrants who were in Portugal at the time are completely absent, and Horse Money is a willful construction of a fantasmatic world devoted to the survivors (and the non-survivors) of that exclusion.

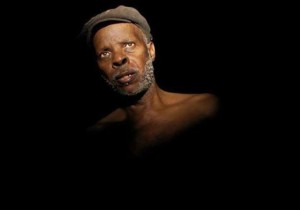

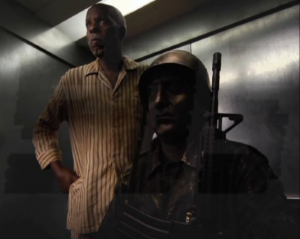

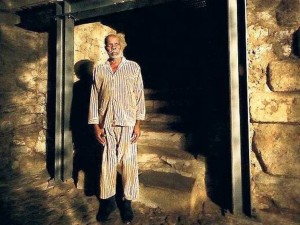

In terms of surface impressions, this 105-minute feature offers mainly a series of institutional spaces, alternately decaying, dark, and prisonlike and tidy but blank and anonymous interiors resembling a hospital through which an ailing and troubled Ventura moves or lingers, his hands often shaking, dressed in pajamas, underwear, or work clothes, as well as ruined work spaces suggesting his former employment in construction (where his godson also appears, saying he’s been there for 20 years awaiting an overdue paycheck). Occasional exterior shots, which also include a forest at night, only extend the Caravaggio-like gloom, as in some of the films of Val Lewton and Jacques Tourneur, intensifying rather than alleviating the overall claustrophobia. A few key painful incidents in Ventura’s past, mostly relating to his own teens, including a knife fight in the forest and an arrest by the MFA, are often recounted or recalled, but almost always as if they were recurring in the present — culminating in a lengthy sequence in which he’s stranded in an elevator with a motionless armed soldier covered in dull silver paint who appears to speak (but without his lips moving) along with many other unseen voices. This scene, the first one shot for the film, appears in a differently edited version as Sweet Exorcism, Costa’s contribution to the 2012 portmanteau feature Centro Histórico, and as this alternate title implies, Ventura’s wrestling with his own demons here is a kind of therapeutic exorcism, both confession and trial. “Some people say they make films to remember,” Costa told Peranson. “I think we make films to forget.”

It’s imperative to note that what Horse Money “says” — or, more precisely, what it sobs or sings — is far less important than what it does. In the same interview with Peranson, Costa acknowledges the direct influence exerted by Jean-Marie Straub and Daniele Huillet’s Not Reconciled (1965) — an adaptation of Heinrich Böll’s novel Billiards at Half-Past Nine, covering several decades in a Cologne family during and after the Nazi era that Straub described at the time of its release as follows: “Far from being a puzzle film (like Citizen Kane or Muriel), Not Reconciled is better described as a ‘lacunary film’, in the same sense that Littré defines a lacunary body: a whole composed of agglomerated crystals with intervals among them, like the interstitial spaces between the cells of an organism”.

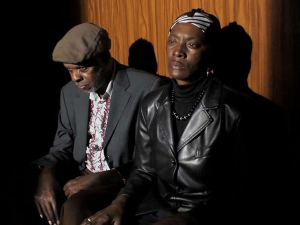

Stated differently, a seeming narrative discontinuity of time, space, and even identity is superseded by an underlying continuity of mood and feeling that belongs to a form of consciousness itself — what might be described somewhat inexactly as public and political consciousness in the case of Not Reconciled and private and personal consciousness in Horse Money. What keeps this description inexact is that it leaves out the more private, even solipsistic manifestations of this consciousness in Not Reconciled as well as the elements of Ventura’s own traumatized consciousness that can be described as shared — shared with a middle-aged woman named Vitalina Varela, another important character in Horse Money, who has returned to Lisbon for the funeral of her husband Joaquin, and shared with Costa himself in the collaborative process of composing/constructing Horse Money with Ventura and a few others.

Vitalina, who has an even more commanding sculptural and vocal presence in the film than Ventura, is often seen and/or heard reciting or reading the contents of official documents relating to the birth and death of her husband, her own birth certificate, and their marriage certificate — most of this delivered in an intense, breathless whisper suggesting her furtive existence as an illegal alien. Ventura periodically tells her that her husband is still alive and in the same hospital, but we don’t believe him — or, rather, we can only believe him in the sense that, as Faulkner put it, the past is never past, that we live only in the present (where the past also continues to live), and when Ventura later gives her a letter that he says her husband wrote to her, we can only surmise that this must be the same letter that we have previously seen Ventura writing, with a pen taken from one of his doctors. When she exchanges her white smock (which makes Ventura wonder if she’s a doctor herself) for black clothing, she gravitates into a ritual with beads accompanying her recitations that suggests voodoo, as if she were in a trance. Identity and ritual are in some ways as fluid and as unstable here as the time frames, and pain is ultimately the only constant. When Ventura, in one of his ruined former work spaces, drags a disconnected phone behind him by its severed cord, which makes a grating sound on the floor, this rhymes plaintively with the sound of Vitalina, newly arrived from Cape Verde, dragging her suitcase across a public square at night.

Since his earliest features, O Sangue (Blood, 1989) and Casa de Lava (1994), made before he arrived at the small-scale and more collaborative methods of his more recent work, Costa has presided over a series of uncanny shotgun marriages between fiction and non-fiction, narrative flow and nonnarrative stasis, the materialism of Straub-Huillet and the immaterial spirituality of haunted, doom-ridden fantasy suggested by Lewton and Tourneur. A hardcore cinephile whose filmmaking taste owes as much to the heroic, sculptural and populist Soviet portraiture of Boris Barnet, Alexander, Dovzhenko, Sergei Eisenstein, and Dziga-Vertov as to the expressive and expressionist lighting and color schemes of such Hollywood artisans as John Ford, Howard Hawks, Nicholas Ray, and Tourneur, Costa has even described Horse Money in commercial, generic terms as a “horror action film,” and the seeming paradox of marrying the blunt realities of a Ventura and a Vitalina with the studio-contrived artifice of a Lewton quickie is central to both his methods and the philosophical suppositions underlying them.

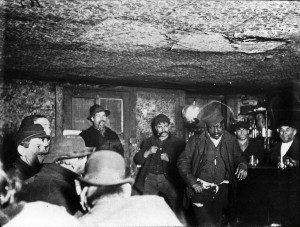

A romantic attempt to bridge the unbridgeable, Costa’s form of alchemy can be contested for its effort to exalt abjection, yet to renounce that endeavor is to deny its tragic poetry and its visionary power. It’s important to recognize that when he begins Horse Money with a display of mostly black and white photographs by Jacob Riis of New York immigrant tenement dwellers in the early 20th century — a disconnected and somewhat awkward overture and prologue matching the heroic portraiture of Cape Verdeans at the start of Casa de Lava, for better and for worse — the tattered condition of the mournful photographs themselves seems as relevant and even as essential to the expressiveness as the dilapidated people and places shown. And there’s an undeniable pleasure as well as pain to be found in the process — most clearly, in a musical montage sequence devoted to lonely ghetto inhabitants that comes midway in the film, offered to us as a kind of gift, a reward to us for waiting. For in effect, the institutional, Kafkaesque nightmares depicted in the film all involve different forms of waiting, and it’s entirely consistent with Costa’s method of sharing that we’re invited to wait endlessly along with his characters, even if this means waiting for some form of deliverance that is unlikely to arrive.