The following is a chapter from my book Film: The Front Line 1983 (Denver, CO: Arden Press) — which I’m sorry to say is only available now at ridiculously inflated prices (one copy at Amazon currently sells for $989.90). It probably remains the least well known of my books. I’m immensely grateful to Jed Rapfogel and Stephanie Gray at New York’s Anthology Film Archives for furnishing me with a document file of this essay so that I could post it here, originally to help promote their Mark Rappaport retrospective in March 2011, prior to the updated version of this held earlier this year. Readers should also consult my separate articles about Rappaport’s Rock Hudson’s Home Movies and From the Journals of Jean Seberg as well as my interview with Rappaport about the latter, all of which are also available on this site, along with a more recent piece about two of his videos. — J.R.

When the critic of a narrative film is feeling desperate, the first place that he or she is likely to turn to is a plot summary. Feeling rather desperate about my capacity to do justice to the last two features of the remarkable Mark Rappaport, I looked up the synopses and reviews of The Scenic Route and Impostors in the usually reliable Monthly Film Bulletin, which appeared precisely three years apart (February 1979 and February 1982), only to discover that each critic, Geoffrey Nowell-Smith and Simon Field, respectively, starts off with the admission that his own synopsis is misleading. “To summarize the ‘story’ of Impostors,” writes Field, “is to misrepresent its structure, to face assumptions of causality and rounded characterization in a film that has no such preoccupations, that loves the red herring, the non sequitur, the scene for its own sake, and in which one person might not be entirely distinguishable from another.”

The fact that Rappaport — a nineteenth-century figure who studied the Victorian novel at Brooklyn College and New York University before abandoning a graduate school scholarship at the latter to become a filmmaker — usually furnishes his features with more plot than one can shake a stick at doesn’t invalidate Field’s point in the slightest. But it does suggest one aspect of the nature of the problem involved in describing his films. And it’s a direct corollary of this problem that Rappaport currently occupies that dreaded no man’s land between the avant-garde and the mainstream that threatens to make non-persons out of most of Rappaport’s European contemporaries as well. (I’m writing this in late February, less than a week after an entertaining black-and-white “art film” clever enough to predict its own doom in this country, Wim Wenders’ well-titled The State of Things — winner of the Golden Lion Award at the last Venice Film Festival, contemptuously rejected by the last New York Film Festival — was brainlessly and pitilessly buried by a New York Times review that couldn’t even tell two of the major characters apart: a movie that obviously commits the grievous error of not catering to the right crowd. In a way, for all their radical — and perhaps even irreconcilable — differences, Wenders and Rappaport share the same handicap in one respect: they make intelligent films in English that ultimately belong to a European as opposed to American frame of reference, despite the central importance of Hollywood to both directors.) And the fact that Rappaport isn’t a European even though he gets treated like one only complicates the injustice.

To keep things manageable and separate, I’ve generally avoided listing work in video by filmmakers in this book (which makes for certain omissions — and major ones in the case of filmmakers like Louis Hock, whose recent work is all in that medium). But having seen and benefited a great deal from Rappaport’s own 28-minute Mark Rappaport: The TV Spinoff (1980), it’s hard to avoid mentioning it here, because it’s the best possible introduction to Rappaport’s film work that I can imagine — and an ideal one or anyone who’s encountering this filmmaker’s original, unsettling work for the first time. As a very witty précis of what watching (and financing and making) his movies can be like, I doubt it could be much improved upon. (Come to think of it, this provides another intriguing point of comparison with Wenders, whose short film Reverse Angle 1: New York, March 1982, initially made for French TV, is equally helpful about Hammett and The State of Things.) At the outset, when Rappaport is trying out different kinds of music with different movie stills — just a formal variation, really, of his subsequent tryouts with different costumes, backdrops, front-projections, plots, characters, clips, and raps about his movies — he’s already setting up the paradoxical parameters of his glamorously homemade cinema. (“All bourgeois dreams end the same way,” snarls a character called Chuckie, played by Charles Ludlam, in Impostors. “Marry royalty and escape.”)

It’s a place where the writer-director and his resourceful actors and crew are all studiously working their asses off to furnish the audience with a kind of do-it-yourself melodrama kit, at once firmly overdetermined and subtly undermined — full of hysteria and intrigue, signifying everything. Rappaport is interested in props and scenic designs, he explains at one point, “not to recreate reality but to suggest a different one.” It’s no wonder that he’s respected more and known better in Europe than in this country, where the zeitgeist often seems like the only game in town.

As suggested earlier, Rappaport fills most of his movies with enough old-fashioned plot to support an entire course in nineteenth-century fiction; there’s also enough bitchy dialogue to stuff Joseph Mankiewicz’s closet (a line from Impostors: “Actually there’s not much difference between being dead and being in Vermont, if you know what I mean.”) He simulates opulence in his studio sets — all established within the confines of his lower Manhattan loft and generally shot by the very able Fred Murphy (who was also responsible for operating the camera in The State of Things) — and class in his talented cast. He then uses these elements in part like filtering screens, each of which emotionally and effectually blocks off a portion of all the others. The results of this elegant, intricately tortured process can be humorous and entertaining as well as creepy and uncomfortable. The dramas turn out to be at once so florid and so private that they can improbably suggest a full-scale opera staged at the bottom of a well, or 2001 seen on a bite-size TV screen. For the first ten minutes of The Scenic Route one might laugh uproariously; for the second ten minutes, one might twitch or flinch — but neither response can comfortably sustain itself indefinitely without some enormous act of repression. Stated differently, Rappaport’s films are bright, impossible objects, motored by obsession and protected by wit, neither of which is effectively allowed to cancel out the other.

For a good bit of its tight, elegant construction, The Scenic Route depends on a European art film staple — the leading character who narrates his/her story off-screen, a direct descendant of the first-person novel, in this case a worrywart heroine named Estelle (Randy Danson). To get her plot out of the way, in standard Monthly Film Bulletin style, let’s turn to Geoffrey Nowell-Smith’s helpful synopsis (to which I’ve appended a couple of actors’ names; others in the cast, one should note, include filmmakers Eric Mitchell and Claudia Weill):

A woman, Estelle, describes in voice-over a painting of Orpheus and Eurydice. She is then seen writing in her diary, and the voice-over continues, now describing events she remembers and is relating in the diary. Various scenes from her life are then accompanied by voice-over or occasionally by sync dialogue. She is assaulted by Jack, her estranged husband; she witnesses a stabbing in the street; she acquires a new lover, Paul [Kevin Wade], and is in his company when another stabbing occurs, this time in a swimming pool. The relationship develops: she gives Paul her ring, he gives her his address book. After the arrival of her sister, Lena [Marilyn Jones], she begins to see Paul less often, preferring to cultivate her relationship with her sister. Lena takes to picking up men in the street and bringing them home; one turns out to be Jack, causing Estelle some embarrassment; another is Paul, which is even worse, since he soon moves in as Lena’s lover. Estelle consoles herself with visions of going on a journey, and with the fond belief that she is Paul’s real beloved — Eurydice to his Orpheus. But more violent thoughts obtrude, including the death of the lovers at the hands of a maniac killer. No resolution to this triangle is found; Estelle returns to her diary, and comments, “In my notebooks it ended like this.” (1)

In keeping with Rappaport’s nineteenth-century-novel preoccupations, one should note in passing both the theme of incest (no less important in Impostors) and the rather absurdly Heathcliffian romantic figure cut by Kevin Wade’s Paul — quite comparable, all things considered, to Barbet Schroeder’s Olivier in Céline et Julie vont en bateau as a figure representing the stiff, charred remnants of that novelistic (and specifically Gothic) tradition.

To Nowell-Smith’s summary we should add some of Rappaport’s own descriptive and analytical comments. The first paragraph is a statement written by him to introduce the film; the last four come from an interview with Tony Rayns in the February 1979 Monthly Film Bulletin:

Love, jealousy and revenge. All standard components of melodrama — but a very “dry” melodrama. Expectations are thwarted and rechanneled. Instead of explanations and motivations, visual counterparts are offered. The film slides back and forth between passion and an irony which redirects it but doesn’t dilute it. A film about myths and myth-making, about the Madame Bovary in each of us, about delusions and romance in a fragile world where violence erupts randomly and unexpectedly. The film was made very cheaply in and around New York, where violence is a way of life and everyone always talks of going away.

The various elements only really fall into place when the narrations are there. The use of narration in low-budget films in general brings us back to finance; it’s cheaper and more accessible than sync-sound dialogue. But I like narration: I like the fact that you can create a discrepancy between what characters say and what you see of them. It’s something that we’ve learned from Melville, via Bresson. I think it’s an incredibly rich technique; it allows you to concentrate on essentials. Plus my mind is always full of ironic double-think … always re-assessing, always re-evaluating.

Movies like Out of the Past and Sunset Boulevard used narration for exposition, as a device for opening the closed door, always from a single character’s point-of-view. I try to use it more centrally: what happens if you use narrations from five points-of-view?

I once described the entire script of The Scenic Route to someone (not the truncated version that I put on the screen), and he thought it was very dry, very dehydrated. But there’s enough material there for five of the melodramas that Warner Brothers used to do! Only with all the melodramatic juices pumped out. The elements of melodrama (and of theatre) that I like have more to do with painting: it’s the gesture, the mise en scène, the lighting, the arrangement, the pregnant moment right before something happens or right after it has.

The emotional tenor is not parody. If I’m parodying anything, it’s the fact that we can only respond to emotional situations in prescribed ways. They’re the only ways we have to respond to the trite elements of our lives. I guess it’s more a matter of irony than of parody. I rely on associations to previous things as a kind of shorthand. It’s not that audiences have to know which films I love, and I’m not interested in hommages. But it’s all retreads — human relationships have been explored, re-explored, de-explored, and yet we still respond to the grain of truth that we recognize at the heart of these situations when they’re represented on a screen. One wants the falseness to be true.

One should clarify Rappaport’s statement about narration by mentioning that his notion about five points-of-view is theoretical rather than actual (although Local Color comes close at times to that level of intricacy, and The Scenic Route intermittently uses Lena as a second narrator). Nevertheless, the sort of distinction he draws between his own work and Hollywood melodrama is accurate in its broad outlines, and it’s important to keep in mind that however well Rappaport knows the American cinema, his films are probably closer to the novels of Alain Robbe-Grillet than they are to the movies of Ernst Lubitsch, Joseph Mankiewicz, or George Cukor.

But as Rappaport himself indicates, it’s the melodramatic and theatrical side of painting that perhaps comes closest to his concerns. And from one point of view, what could be more melodramatic and theatrical than the American flag? (Consider the cornball rhetoric of its flaunting by Robert Altman at the end of Nashville — the kind of pretension that invariably suckers xenophobic, all-American patriots who criticize European films for their “heaviness.”) And it is the American flag whose formal coordinates are used in the obsessively reiterated picture of Orpheus and Eurydice glimpsed at the beginning —an icon and reference point that is restaged and rethought as often as the old photograph of the Chinese couple that begins and ends Leslie Thornton’s Adynata. In certain variations of this mythical pose — a man watches an ornate woman sleeping in an ornate bed — part of the wall and bed spell out precisely those coordinates, as if to give one more expression to the European vs. American and classical vs. romantic feuds being waged in this movie.

Rappaport is invariably at his best when thinking up ingenious compositions of this kind. Two other strong examples in The Scenic Route involve screens between people: slides of atrocities winking on and off between Estelle on screen left watching her sister Lena kissing Paul on screen right; Estelle at one end of a row of movie seats, a man at another, while enormous black-and-white close-ups of a couple kissing play on the movie screen over their heads (entailing an odd yet satisfying reversal of directions because they’re both looking away from the screen). Still another striking melodramatic effect is achieved in a shot between the two previous examples, when Estelle backs away from Lena and Paul only to wind up next to a gigantic black-and-white photograph of the same couple, discovered at the end of a camera movement that follows her stealthy retreat. Still later, after Paul buys a record of Gluck’s Orpheus and Eurydice (2), one twice sees the ornate wallpaper in Estelle’s flat rise like a curtain to reveal each sister standing outdoors in front of the same autumnal landscape; then a backdrop of snow-capped mountains also lifts behind Paul to show that he’s standing in the same spot previously occupied by the other two.

The desire to be part of a work of art infects virtually every register of representation broached by the film, keeping one’s distinctions between subjective fantasies and objective narrative information almost as confused as their respective emotional impacts. Paul and the two sisters dance in Estelle’s living room at one point to a rock tune (“Dr. Love”), and the effect is as wonderfully deadpan as the performance of the Madison by the goofy trio (two males and one female) in Godard’s Band of Outsiders. Some of the equally deadpan lines are just as funny, particularly in their mockery of New York clichés of attitude and intonation. “I was afraid to go out — I was afraid to stay in,” Estelle remarks early on in the narration, not before she’s seen walking outside when a woman with a dagger in her back falls rather promptly into her arms (echoing the United Nations corpse near the beginning of Hitchcock’s North by Northwest). Estelle’s morose follow-up comment is just as crazy in its banality: “It was the first time I ever touched someone’s blood. It was also the day I got a letter from Lena….” “I think I’m ready for a meaningful affair,” she says elsewhere; and Paul at one point utters a line that perfectly catches the claustrophobic, paranoid mood of pose and posture at the point of self-mockery: “I wouldn’t even tell you a lie, much less the truth.” “I feel uneasy with you,” Estelle responds, understandably.

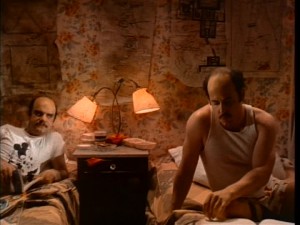

Impostors isn’t my favorite Rappaport film — I’d assign that place to the infinitely plotty Local Color, with The Scenic Route a close runner-up — but with a $115,000 budget and an all-star cast, it’s probably the most lavish, in thought as well as deed. (Readers interested in details about the making of the film should consult my production story in the October 1979 American Film.) The daisy-chain of flirtations, passions, jealousies, relationships, and correspondences between a well-to-do romantic hero (Peter Evans), a pair of murderous magicians impersonating a pair of twins (Charles Ludlam and Michael Burg — the latter a leading actor in Local Color), their enigmatic assistant (Ellen McElduff), and her mysterious soulmate (Lina Todd), are so complexly interwoven that after a while, döppelgangers proliferate like bunny rabbits.

Each couple and/or two-way pattern threatens and comments on every other, so that straight and gay sensibilities, male and female characters, and passive and aggressive roles seem perpetually at loggerheads, fighting their way through insults and betrayals into bitter, neurotic stalemates. What’s even stranger is that all the males seem at times like different facets of the same personality — a characteristic that this movie shares with two of its reported thematic reference points, Proust’s La Prisonnière and Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon (as filmed by Huston).

A lot of the time, it’s difficult to know whether to laugh or scream, and like certain other obsessive directors, Rappaport often tries to have it both ways — keeping the viewer distanced and testily daring the viewer to get involved and/or pissed off at the same time. Ludlam, in particular, is a superb needler who works with macabre camp as if it were a delicate instrument, stretching out his cackling effects into cadenzas.

“So many corpses, so little treasure!” wails Burg, the other weirdo magician in the movie; he could just as well be talking about the diverse deadends and rewards of narrative itself. To say that Impostors doesn’t “work” finally isn’t to say much at all. Louis Malle’s Atlantic City, released the same year, works like a charm, but leaves one with next to nothing afterwards — like a good meal you forget about the following day, or a Jacques Demy movie that makes you feel pleasantly nostalgic about your own dreamy narcissism, without forcing any of the accompanying impostures into a state of crisis.

Impostors, a good deal stickier, leaves me with something more. After seeing it three times, it still drives me a little batty (as it no doubt should). To my taste, the women in the movie are too elliptical and remote (as are the men in The Scenic Route), the Peter Evans character too well armored against ridicule, and the dialogue too doggedly flashy in spots. (One character compares love and romance to an artichoke —“you peel it all away, and there’s nothing left” — when what she or Rappaport apparently means is an onion.)

But there’s a lot more rattling around inside the possibilities of this oddball romantic epic than one can find in most places, and viewers who like to take (and honor) bold risks should give this movie a chance. You might wind up hating it; but even if you do, you’ll probably have some interesting reasons you never would have thought of otherwise. (After all, all bourgeois dreams end the same way — inside someone’s head.) And either way, I can guarantee that you’ll have plenty to look at, listen to, and think about, both here and in The Scenic Route. The fact that Rappaport has a good eye, ear, and mind already places him well ahead of most of contemporary cinema. He merely has the misfortune of living in the wrong century and on the wrong continent, meanwhile making the best movies that he can.