From Cineaste, Winter 1996 — J.R.

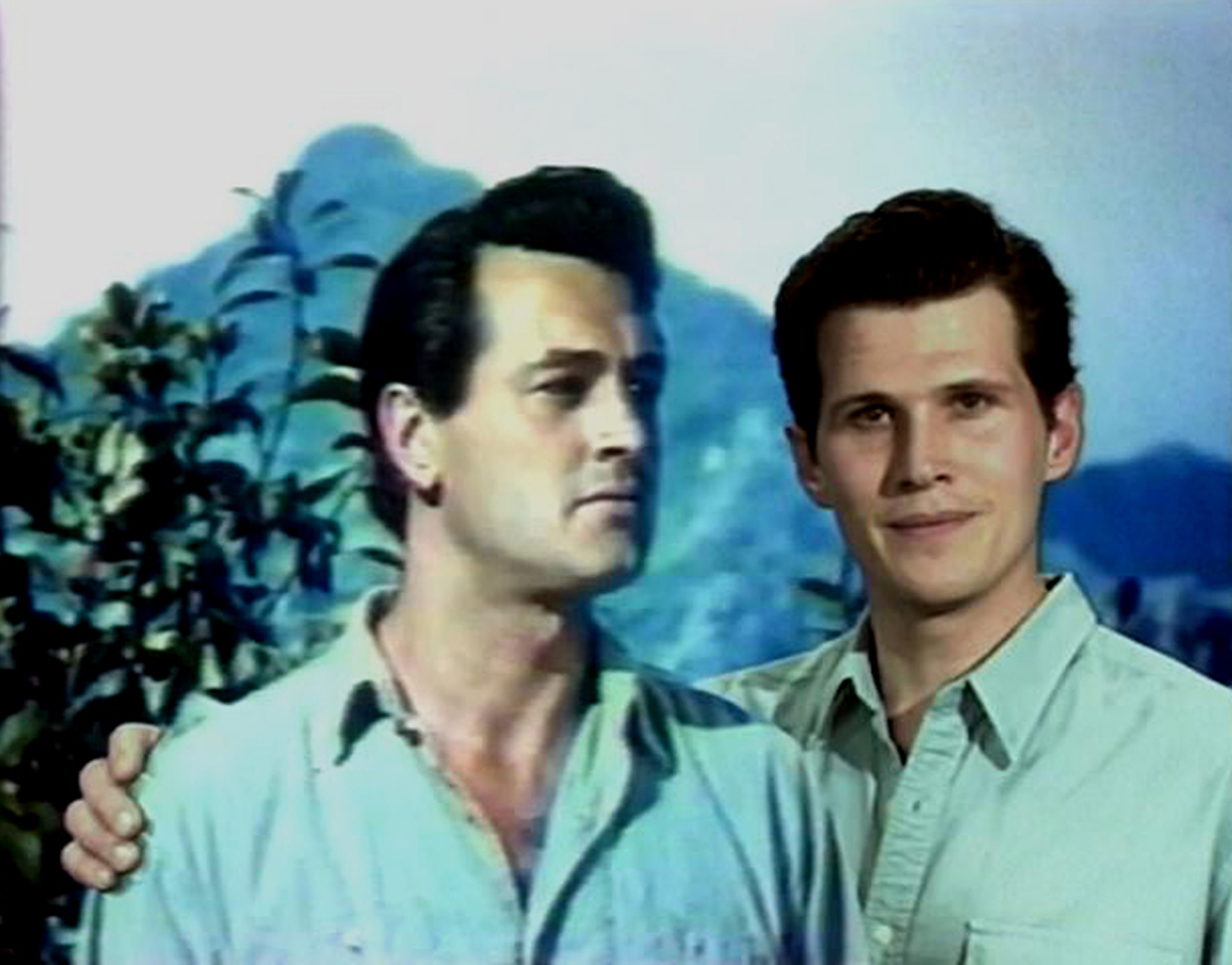

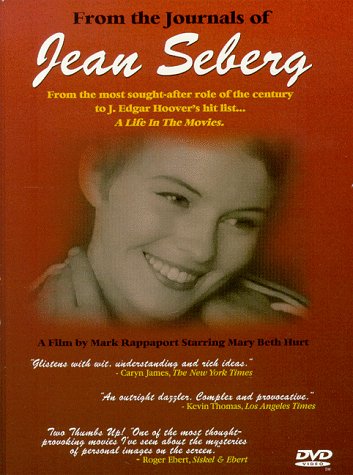

Even for longtime fans like myself of his independent features — Casual Relations (1973), Mozart in Love (1975), Local Color (1977), The Scenic Route (1978), Imposters (1979), Chain Letters (1984) — Mark Rappaport’s discovery of “fictional autobiography” has led to a quantum leap in his work whose consequences are still being mapped out. After already broaching some of the possibilities of video in his half-hour Postcards (1990) — succeeded most recently by his high-definition super-production Exterior Night (1994) made for German TV — Rappaport virtually invented a new form of film criticism in Rock Hudson’s Home Movies (1992), a melange of clips and commentary built around the premise of a finally out-of-the-closet Hudson (played by actor Eric Farr) reevaluating the subtexts of his films from beyond the grave. A video that won Rappaport more viewers than any of his previous features — especially after he transferred it to film and presented it at festivals — this revisionist take on film history has now been succeeded by From the Journals of Jean Seberg (1995), an even more ambitious and accomplished rereading of our movie past, with Mary Beth Hurt in the title role. After many festival screenings, the new film had its U.S. theatrical premiere at Chicago’s Film Center in January and has subsequently been opening in other major cities.

A friend of Rappaport’s for almost two decades, I had plenty of occasion to argue with him about Jean Seberg before he even completed the work, so in a way our interview, conducted in New York shortly after the New Year, was only the continuation of a conversation that had been going on for months. For the record, I have a higher opinion than he does of Seberg’s acting as Saint Joan in her first feature (made, like her second, Bonjour Tristesse, by Otto Preminger) — a role played after thousands of other actresses were tested for the part in a well-publicized search across the country. And, partially as a consequence of having met Seberg briefly with her second and third husbands, Romain Gary and Dennis Berry, in Paris in 1973, I tend to be less judgmental than Rappaport about her treatment by her director-spouses, if only because I feel that neither of us is qualified to deliver any verdicts about this. But as esthetic strategies, Rappaport’s arguments seem harder to quarrel with; the crucial point is that his film be taken as fictional essay, not as documentary. — Jonathan Rosenbaum

Cineaste: How did you get from Rock Hudson to Jean Seberg?

Mark Rappaport: Originally, I was going to do another tape after Rock Hudson about the representation of art and artists in mainstream Hollywood movies. I had transferred and edited a great deal of footage. Sorting it out, cataloging everything and putting it in its proper category, took forever. I edited about fifteen minutes and then I realized that, first of all, the issue is not a burning one — it’s of interest to me and about four other people in the whole world. Also, without the ‘spine’ of a single character or the form of an autobiography, it just didn’t hold. In order for this approach to really work, the clips have to be structured around a format. The fictional autobiography, as I call it, is a form that’s very useful, insofar as it structures the material and also enables you to digress and do tangential riffs and curlicues. There are many leaping off points and you can always snap back to the original spine.

Cineaste: It also makes it a narrative, doesn’t it? I assume that you didn’t have a narrative in the piece about art and artists.

Rappaport: No, you’re quite right. Biography or autobiography is always by its nature a narrative.

Cineaste: Was the basic research on Jean Seberg, apart from looking at films, reading the one biography written about her, Played Out: The Jean Seberg Story by David Richards?

Rappaport: No, the real research was the films themselves because, basically, I’m reading the films as her autobiography and everything that I glean from the films becomes a way of illustrating her life. I use the films as the main text. In fact, the biography is only a minor, subsidiary text. There’s very little in the Richards biography that isn’t widely known. In fact, I think one of the main drawbacks of the book is that he didn’t see a lot of her films and really was not able even to interpret the films that he saw in any kind of meaningful way.

Cineaste: One potential danger of this type of film is that it could be mistaken for a documentary. So one could theoretically come away front From the Journals of Jean Seberg thinking, “I know who Jean Seberg was,” as opposed to “I know what happened to Jean Seberg,” which is something else entirely.

Rappaport: Well, I certainly don’t pretend to know who Jean Seberg was, and, in a sense, I’m really not interested in that aspect of it. People say to me, “But, you know, I still don’t understand why she did what she did.” Which is totally irrelevant. I mean, I’m not interested in her psychology. Psychology is pretty much a boondoggle — very often a way of trying to explain the unexplainable. It’s ‘Jean Seberg’ the construct, who is the sum of all of her movies, that’s interesting to me. It’s the persona that’s recreated through artificially created images that I find fascinating. I didn’t know her and I’m not really that interested in the day to day existence of her life and what she may have thought, what she ate, whom she slept with. I’m interested in what she left behind — her films and what is projected in those films.

In addition, I’m not responsible for what people come away with from movies and least of all my movie. This is not a cradle to grave biography, this is not a standard PBS biography, nor does it pretend to be. It’s very clearly a dissection of images of her as they are presented on the screen. I recently saw a bio of Nico [Nico Icon – ed.] and all the interviewees want to do is talk about how empty she was, how boring she was, how she was not able to love anyone, and so on. I would hate to have my life defined by people who didn’t know me very well or didn’t have the words to describe me the way I would have described myself. It does become a problem of language. And perception. And psychobabble. The message to be learned from those kinds of bios is that you should never die, and, if you have the bad fortune to die, just make sure that no one makes a documentary about the ‘real’ you — whoever that is!

What does a biography really tell you? It’s a very limited perspective of what the biographer has researched, how well they’re able to put it together, what they leave out, what they put in, their ability to describe what they put in, the order that they put it in. It’s all incredibly colored by the writer. And autobiography is the ultimate lie. How much truth can the person writing tell about his or her life, really? They’re retelling a life from a very limited perspective. I’m not saying that mine is less limited but it’s more social/cultural/political. There is a certain kind of authenticity in the clips themselves. I didn’t write or direct or light or edit those movies. I’m using them as primary documents.

Cineaste: One of the key things that I think Jean Seberg and Rock Hudson have in common is the extent to which their films were about the denials of who these people were.

Rappaport: But isn’t that what all films are about? Isn’t that what movie acting is about?

Cineaste: How did you wind up choosing Seberg?

Rappaport: I had read in the papers that Jodie Foster was going to produce and star in the life of Jean Seberg and I said to myself, ‘I’m going to do this before she does.’ She wasn’t even born when Breathless was released. For her, Seberg was, at best, a ‘historical’ figure. For me, she was contemporary, and had a lot of resonances that I thought I could explore in ways that Foster never would be able to.

Cineaste: Is that project still on?

Rappaport: No, I think it’s dead in the water. Well, perhaps that’s not the most generous impulse to stoke the fires of a film but, so be it, that’s what really got me going. I felt that my relationship to Jean Seberg, even though I never met her, was much closer because I partook of the times and I remembered her very vividly, even from the Saint Joan contest.

Cineaste: Were you a fan?

Rappaport: Well, I hate that word ‘fan,’ but I guess I was. At the time that her movies came out, in the Sixties and early Seventies, I went to see every one of them that was released, except for Airport. I kind of drew the line there.

Cineaste: People who had a certain relationship to her films, including myself, feel rewarded by this film because, for instance, even though you have very little from The Five-Day Lover (1961), you have the theme song, which everybody remembers from that film.

Rappaport: I wanted to use The Five-Day Lover, but, as far as I know, there no longer exists a French print with English subtitles. I was able to get a German dubbed version. It’s just too complicated to explain why you’re using a German dubbed version of a French film and then translate the German to English. The lack of authenticity multiplies the further away you get from it and I just didn’t want to get into that.

Cineaste: You have a little history of the playing of Joan of Arc in various movies, but there are some that you don’t mention and I’m wondering about those — Bresson’s Le procès de Jeanne d’Arc and Rivette’s recent Jeanne la pucelle.

Rappaport: Maybe the French doing Joan of Arc with a French actress can escape the wrath of the gods. Maybe the curse applies only to foreigners stomping on this terrain that they’re really unfamiliar with. I guess the next one up is Kathryn Bigelow’s version of Joan of Arc, which sounds like a project of doom from the get-go.

Cineaste: Your film is obviously a form of film criticism, and an important part of the social commentary has to do with elements that people didn’t see in the films when they came out. I can even remember critics who wrote about Birds in Peru, for example, as a sort of guilty pleasure because it was campy and baroque, but you didn’t encounter words like ‘misogynist’ or ‘sexist’ in their prose — not in 1968.

Rappaport: Those words may not have been coin of the realm in those days, but if you didn’t know that it was a film that was incredibly degrading and humiliating to the actress, the wife of the director, your head was screwed on some other part of your body.

I do remember seeing Rocco and His Brothers in 1960 and was just made incredibly uncomfortable by the treatment of Annie Girardot’s character. The treatment of the men towards her was execrable and I knew that she was just a subterfuge for the two guys to ‘connect.’ Why didn’t Alain Delon and Renato Salvatore get together and do it with each other without pretending to use Girardot as the go-between? I knew that was a subtext. I couldn’t give words to it at the time but the abusive way the woman is treated made me incredibly uncomfortable and very angry with the movie. Even when the movie was rereleased about two or three years ago, nobody mentioned how misogynist the film is, and how the woman is just a pretext for the men to just adore each other.

In fact, I was going to do a section on Godard’s Letter to Jane and, in my version, Jean Seberg says she was afraid that Godard would do the same thing to her because of her involvement with the Black Panthers. Of course, what Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin did to Jane Fonda in Letter to Jane shouldn’t happen to a dog.

Cineaste: Why did you leave that out?

Rappaport: The film was the length that it is now and I felt that it was not necessary. It would have made it too long and it’s strictly for the handful of people left in the world who remember what Letter to Jane is.

Cineaste: Of course, Vanessa Redgrave has probably been targeted for her radical politics as much or even more than Jane Fonda or Jean Seberg.

Rappaport: Well, on the other hand, Vanessa Redgrave, unlike Jane Fonda and Jean Seberg, is a great stage actress and can always work in theater, in England and even in America. So, it’s almost irrelevant because she has work, and very fulfilling work.

Cineaste: Let’s talk about Breathless — the idea of the blank expression, the tabula rasa, which leads into your discussion in Jean Seberg of the Kuleshov experiment. Are you saying that Breathless established a kind of acting style that hadn’t existed before?

Rappaport: Well, no, because whatever Seberg does in Breathless, she’s already done in Bonjour Tristesse. She looks at the camera for achingly long periods of time, with zero expression on her face, and her voice-over accompanying it. This was the first time that kind of technique had been appropriated. Although there’s that scene in Bergman’s Summer with Monika in which Harriet Andersson looks directly at the audience, breaking the fourth wall — as if to blame or at least make the audience complicitous with her behavior.

Cineaste: Some people say that your restaging of the Kuleshov experiment — cutting together the same actor’s neutral expression with other shots — only proves that the experiment doesn’t work the way it’s supposed to.

Rappaport: I think it proves that the Kuleshov experiment does work because that’s what screen acting is — it’s acting and reacting. You cut to what the actor’s looking at and then you cut back to the actor’s face and see how the actor is responding to what he or she is seeing. It was a formalist experiment. Perhaps the specifics of the experiment — cutting to a coffin, then to a bowl of soup, then to a child playing — don’t work. But it set down the parameters of how the actor is intercut with what the actor sees. It clearly does work. Films are made exactly the same way today as they were made when that experiment was made in 1918 — nothing has really changed.

Cineaste: How good an actress do you think Jean Seberg was?

Rappaport: It’s very hard to say. I think she had something very special. This is for sure. I think she’s terrific in the scene I use from Paint Your Wagon, which was her audition scene — where Lee Marvin practically rapes her (in the real film, it’s much, much longer). She’s wonderful in Breathless, she’s wonderful in Five-Day Lover, she’s extraordinary in Lilith — which is not a movie I like very much, but I think she gives a great performance.

Talk about editing, that’s a movie in which all of her scenes are truncated because they have to cut away to Warren Beatty looking at her talking. So in the pivotal moments of her speeches you get a shot of Warren Beatty looking drugged, uncomprehendingly looking at her. I think actors and actresses, just like anybody, can be stretched. It depends on what kind of material they’re offered. I don’t think she was a great actress like Redgrave or Moreau, but she had something very much her own.