From the November 20, 1992 Chicago Reader. –J.R.

ROCK HUDSON’S HOME MOVIES

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed and written by Mark Rappaport

With Rock Hudson and Eric Farr.

In the creation of art, the verb is there to authenticate the subject with the same name.

To paint is the act of painting. . . . To write becomes the act of writing and of the writer. To film, that is, to record a sight and project it, is the act of cinema and of the makers of films . . .

Only television has no creative act or verb to authenticate it. That’s because the act of television both falls short of communication and goes beyond it. It doesn’t create any goods, in fact, what is worse, it distributes them without their ever having been created. To program is the only verb of television. That implies suffering rather than release. — Jean-Luc Godard

You were a great star, Mr. Hudson — one of the biggest. Sorry it all had to end like this. — director Mark Rappaport’s voice in Rock Hudson’s Home Movies

The precipitous decline in the quality of American movies since the 1970s can be attributed to several factors, but three interconnected changes in U.S. film culture seem especially relevant: (1) the near disappearance of serious film criticism and the enormous growth of film publicity, which has effectively replaced criticism; (2) the gutting and political muzzling of an already minuscule program of state funding for independent filmmakers, a key means of survival for artistic filmmaking elsewhere in the world; and (3) the proliferation of VCRs and the simultaneous decline of communal public spaces for filmgoing.

The first two changes are to my mind unambiguous disasters that have effectively handed over the future of American cinema to stupid, tasteless merchandisers with none of the old studio heads’ savvy. The current moguls, without imagination or vision, have no compunction whatever about forcing their demographic conclusions on audiences, both developing and exploiting the spectator’s passivity in relation to the film industry and eliminating most options outside it. The third change, on the other hand, despite the overall damage it’s done to the social and theatrical aspects of moviegoing, also carries a new, radical potential: spectators can become active, critical, creative, and selective — not only more discerning in what they choose to see but producers in their own right.

When I purchased my first VCR, in the early 80s, I spent the first few days creating impromptu montages of films showing on separate channels. I could “cut,” say, from a reaction shot of a frightened Ingrid Thulin in Bergman’s arty The Silence to a shot of Rod Steiger as the villain in Oklahoma!, implying it was Steiger’s “poor Judd” who was upsetting Bergman’s neurotic heroine. A few months later I heard about “scratch videos,” a short-lived English art movement that grew out of comparable play with VCRs (the machines first became widespread in England a year or so before they did in the United States). I never actually saw a scratch video, but I know that experimental film critic Michael O’Pray curated a whole show of them about a decade ago.

Unfortunately, neither my own form of play nor scratch videos remained a creative outlet for many people; the purely passive recording of the creative works of others took over. But in 1989 Jean-Luc Godard broadcast the first two parts of a projected ten-part TV series still in progress, Histoire(s) du cinéma; essentially this series raises the art of scratch videos to the complex polyphonic level of symphonic fugues and Finnegans Wake. (After many screenings at European festivals, these two parts recently premiered in New York at the Museum of Modern Art’s Godard retrospective; whether they will be shown more widely is still unclear — it’s virtually impossible to subtitle them.)

And now Mark Rappaport — one of our finest independent filmmakers, a writer-director essentially forced into silence by the evaporation of state funding until he discovered video, in his 1990 Postcards — has created the first major American video in this genre. A work of revolutionary implications, it both addresses and works within the parameters of all three basic changes in movie culture listed above. (Happily, Rappaport is already at work on more videos involving film clips, and it would be nice to see other filmmakers strapped for cash trying this form on for size.)

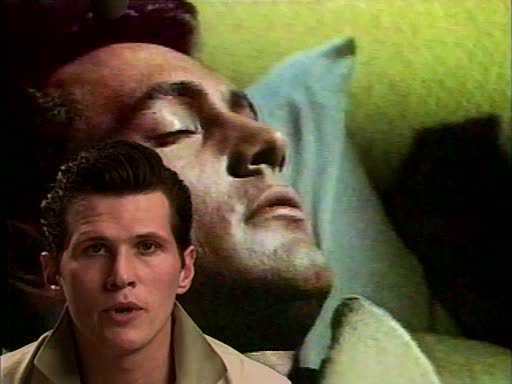

A work of radical historiography that seeks to convert us from passive to active spectators, the 63-minute Rock Hudson’s Home Movies, playing at the Film Center this weekend and next, begins with a movie clip of Rock Hudson writing while his voice says offscreen, “In the interest of truth and justice, I have set down the unvarnished facts of my life — my own story in my own words.” Another voice, actor Eric Farr’s, briefly takes over: “And especially in the images of the movies I was in.” Then Hudson’s voice resumes: “Let people judge for themselves.”

Then, while we hear Doris Day sing the title song of Pillow Talk, we see a color still of Hudson looking out an autumnal, windswept window in Written on the Wind; over this appear the words “Rock Hudson,” followed by the remainder of the video’s title, so it reads “Rock Hudson’s HOME MOVIES.” Hudson’s name remains on the screen to become part of two other configurations: “by Rock Hudson and MARK RAPPAPORT” and “starring Rock Hudson and ERIC FARR.”

Hudson’s and Farr’s voices at the beginning, the emblems appropriated from two Hudson movies, and the two kinds of lettering in the credits all point to troubling and unresolved issues about who Rock Hudson was and is in relation to his audience — artistically, socially, and historically. Such issues even relate to the ways I’ve chosen to represent the script and cast credits in the heading of this review. The video does make some use of Hudson’s own (reported) statements in interviews as well as his movie dialogue (though that was written by others), so it might be argued that the video was “written” by Hudson as well as Rappaport; but I’ve chosen to equate Rappaport’s editorial control with his authorship. On the other hand, it’s surely appropriate to say that the video “stars” Hudson as well as Farr (an actor hired to represent Hudson discussing his own life) despite the fact that Hudson made no decision to appear in it.

The fact that Farr “represents” rather than “plays” Hudson has led some reviewers to criticize his performance, Rappaport’s direction of it, or both. But it seems to me that an accurate impersonation of the star is not at all what this video needs, considering its exploration throughout of a “bifocal” vision that juxtaposes one fiction against another rather than a “real” Hudson against an imagined one.

The emotional register of much of Rappaport’s work has a similar uncomfortable duality: often peppered with clever wisecracks that suggest the urbanity of a Joseph L. Mankiewicz, it’s also suffused with melancholic moods and desperate observations that border on the tragic and the nightmarish. To criticize this duality as failed or strained jokes — a common misreading of Rappaport — is tantamount to rejecting the work’s challenge and complexity and opting for something altogether safer, such as a typical Rock Hudson movie. To accept it is to emerge from a good many laughs and a fair number of winces feeling bereft, sad, and more than a little wiser.

If we raise the ethical question of whether Rappaport has the right to “cast” Rock Hudson without his consent, then surely that question also needs to be raised — and indeed is raised by the video — about the Hollywood movies in which Hudson appeared. Here it’s not a matter of legal agreements but of how little Hudson was in control of these films’ meanings, how much he himself was a text written by Universal Pictures, director Douglas Sirk, various screenwriters, the whims of his public, and so on.

By assigning Hudson a hypothetical voice in this matter Rappaport opens up a fissure in the Rock Hudson text that no amount of studio hype and industry gush can close. For as the video repeatedly shows, the countless movies in which Hudson appeared, always in stereotypical heterosexual roles, were not so much indifferent to Hudson’s homosexuality as they were hyperaware of it, with the grotesque consequence that double entendres and innuendos about Hudson’s sexuality abound. Some of these allusions were undoubtedly accidental, though they’re certainly ready to be unpacked as Freudian slips — “the return of the repressed” in all its fury. Hudson’s apparently passive and compliant response to this constant humiliation becomes equivalent in certain ways to the spectator’s passive and ultimately alienating relationship to Hudson’s false roles and postures, a relationship held in place by the same ideology. Whatever the source of these Freudian slips, it’s impossible to imagine that Hudson was unaware of most of them, and the bulk of Rappaport’s video explores this disquieting fact, outlining a lost chapter in film history that can be perceived today only speculatively, through a fictional gay Hudson we can now juxtapose with the fictional straight one.

But Rock Hudson’s Home Movies is even more a work of film criticism than of film history, though this is criticism couched in the form of pseudoautobiography. It begins with Hudson (Farr) telling us what first made him want to be a movie star: at the age of 12 he saw Jon Hall dive from a ship’s mast in long shot in John Ford’s 1937 The Hurricane (a clip we contemplate more than once). Years later Hudson met the stuntman who made the actual dive and realized he’d been fooled into thinking it was Hall. Hudson’s deception about that film mirrors ours later about Hudson himself, a deception terminated only when Hudson was dying of AIDS in 1985 and, uncharacteristically, decided to reveal this information. Public knowledge of his gayness effectively became universal though Universal had concealed it for years. (The studio kept him under contract for most of the 50s and arranged a brief marriage of convenience for him during that decade to keep the scandal sheets quiet.)

Occasionally drawing on some of the “blue screen” special effects with perspective he employed so strikingly in Postcards, Rappaport places the “real” Rock Hudson (in film clips) and the newly shot fictional Rock Hudson (played by Farr) side by side; at one point Farr even stands slightly behind Hudson with his arm around him. The two Rocks are often dressed almost identically, and the juxtaposition of these two fictional versions of the same mythological figure creates a multifaceted critical perspective on the one we remember from such films as Magnificent Obsession, All That Heaven Allows, Giant, Written on the Wind, A Farewell to Arms, The Tarnished Angels, Pillow Talk, Lover Come Back, Man’s Favorite Sport?, Send Me No Flowers, Seconds, and Pretty Maids All in a Row — to cite only a few of the many dealt with here. In a brilliant move Barbara Scharres, director of the Film Center, has programmed two of the most interesting of these — Douglas Sirk’s Written on the Wind (1956) and John Frankenheimer’s Seconds (1966) — with the Rappaport video, thereby allowing it to function more effectively as criticism.

The most persuasive critical tool Rappaport uses, and one that would never work as well in print, can best be described as indexing: piling up examples of behavioral or thematic motifs from different films that immediately and fully demonstrate whatever generalization is being made. Early in the video, for example, we’re asked to ponder the frequency and meaning of interrupted kisses in Hudson’s movies, then treated to five of them in a row, followed by a couple of Hudson’s sustained “scorchers” for contrast. Finally we see the most memorable and disturbing of all the interrupted kisses — when a figure in a skeleton costume bursts in on Hudson and Dorothy Malone during the New Orleans Mardi Gras in The Tarnished Angels. This clip not only serves as a climax to the index entry (which one might call “Kisses, interrupted”), but offers the beginning of another entry (“Death, premonitions of”) that’s picked up much later in the video. (If sexuality is the video’s major subject, death is just as surely its minor theme, often calling to mind Jean Cocteau’s observation that “the cinema films death at work.”)

The most staggering number of index entries undoubtedly are the clips of men cruising one another in Hudson’s movies; by my count, there are five dozen examples in the video, and their cumulative impact is both devastating and hilarious. These instances of male flirtation are presented in various subcategories (such as the male cruising in Douglas Sirk movies and what Rappaport calls “pedagogical eros”) and even certain sub-subcategories (such as the moments of physical contact between Hudson and Otto Kruger, the teacher figure in Sirk’s Magnificent Obsession, and moments of lustful eye contact between Hudson and Tony Randall in the 60s Doris Day trilogy of Pillow Talk, Lover Come Back, and Send Me No Flowers). We’re also given samples of Hudson’s apparent on-screen flirtations with Kirk Douglas, Burl Ives, John Wayne (“putting the make on Duke”), Earl Holliman, Jan-Michael Vincent, and Vittorio De Sica, among others. Rappaport clearly does not feel obliged to limit his observations to Hudson movies, showing us the same suggestive dialogue between male buddies in two versions of A Farewell to Arms filmed a quarter of a century apart — one between Adolphe Menjou and Gary Cooper, the other between De Sica and Hudson.

Although a few die-hard auteurists have had trouble with Rock Hudson’s Home Movies because it emphasizes societal lies and ideological tics over “timeless” personal visions, Rappaport is much too astute to ignore how relevant such directors as Sirk and Howard Hawks are to his arguments. Rappaport links Sirk, who virtually discovered and trained Hudson as a star, to the mentor Kruger plays in Magnificent Obsession without implying that Sirk was gay. (“Pedagogical eros” obviously refers to a lot more besides what some men may do in bed with one another.)

In Hawks’s Man’s Favorite Sport?, Rappaport reads Hudson’s role as “a fishing expert who can’t fish” and “can’t stand the smell of fish” as a mockery of the actor’s sexual orientation and interprets his humiliation as the butt of various physical gags as Hawks’s revenge against Hudson for his closet homosexuality. One may not fully agree with this analysis — it’s not quite as convincing as the commentary on Sirk — but Rappaport does an excellent job of showing how Hawks subjected Cary Grant (for whom the Hudson part in Man’s Favorite Sport? was originally written) to comparable sexual embarrassments in Bringing Up Baby and I Was a Male War Bride without ever signifying the same things in the process. (What he leaves out, I would argue, is crucial: the fact that Grant was a remarkably skilled and graceful actor while Hudson in most cases was wooden and awkward. To hear Hudson attempt southern accents in a couple of the film clips here is to observe star acting at its near worst.)

Other index entries might be the “swishy or effeminate [minor] characters” in the Hudson-Day-Randall trilogy, feminizations of Hudson throughout his career, Hudson’s behavior in macho doctor roles (nine examples), grim forecasts of his later illness and death, and displays of his vulnerability with older women. (Thanks to Jane Wyman, Rappaport is able to call Ronald Reagan Hudson’s “boyfriend-in-law,” just as Angie Dickinson’s affair with John F. Kennedy meant that Hudson’s tryst with her in Pretty Maids All in a Row placed him only “a kiss away from the President.”)

In his indispensable book Stars critic Richard Dyer argues that some stars are popular because they appear to resolve certain contradictions while they also mask them. (Marilyn Monroe’s Lorelei Lee in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, simultaneously conniving and innocent, is one of his clearest examples.) The contradictory butch/femme roles mapped out for Hudson seem at times to partake of this duality, and it might be argued that at least part of the seemingly compulsive exploitation of sexual uncertainties in Hudson’s movies revolves around this complex star function. (That exploitation may also be a crude and cruel commentary on Hudson’s offscreen sexual behavior, but I’m not sure this is quite as programmatic as Rappaport’s video makes it out to be.)

Rappaport plays his new brand of film criticism like a grand organ, periodically freezing and unfreezing the images, whether to concentrate on certain visual details or allow the spoken commentary to dominate. With a great deal of acuteness and dexterity–he’s especially adept in the editing — he begins to show some of the exciting possibilities inherent in this new form. Showing us a way to talk back to the movie mythologies that influence and often corrupt us, even to the point of poisoning our dreams, he suggests that we don’t have to be millionaires or commandeer a television network to enter into a dialogue with the crushing Hollywood machine. At the bare minimum all we need is a will, two VCRs to play with, and something trenchant to say.