From Monthly Film Bulletin, January 1975 (Vol. 42, No. 492). — J.R.

Machorka-Muff

West Germany/Monaco, 1963 Director: Jean-Marie Straub

Germany, in the early 1950s. Colonel Machorka-Muff arrives in

Bonn to see his mistress Inn and continue his efforts to clear the

name of General Hürlanger-Hiss from disgrace after his retreat at

Schwichi-Schwalache during World War II. At his hotel the next

morning, after meeting and exchanging pleasantries with a lower

rank officer he commanded, he also sees Murcks-Maloche from the

Ministry, who informs the Colonel that he is to give the dedication

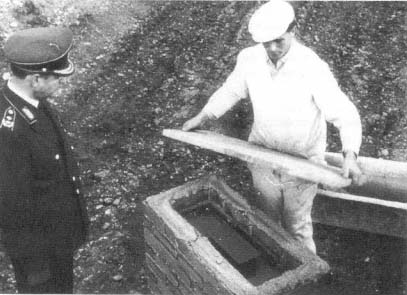

address at the foundation-laying ceremony to inaugurate the

Hürlanger-Hiss Academy of Military Memories. After the Colonel

spends the morning walking through Bonn, Inn picks him up in her

Porsche and they drive to her flat and make love. She wakes him a

few hours later to announce the arrival of the Minister of Defense,

who presents him with a general’s uniform and drives him to the

ceremony; there Machorka-Muff announces in his dedication that

Hürlanger-Hiss made his retreat after losing 14,700 men, not “only”

8,500 as previously-thought. At mass the next morning, Inn

recognizes the second, fifth and sixth of her seven former husbands,

and Machorka-Muff announces that he will be the eighth; afterwards,

the priest explains that there will be no problem in having a church

wedding because all of her former marriages were Protestant ones.

They drive to Petersberg to visit Inn’s family. Murcks-Maloche

comes to the villa to report that the Opposition has expressed

dissatisfaction with the Academy; when Machorka-Muff tells

this to Inn, she replies that her family has never been opposed.

Paradoxically, the above synopsis of Straub’s first film — which

might seem long enough to furnish the plot of a conventional

feature — is in fact a drastic reduction of what is already a sharp

paring down, by Straub and Huillet, of a very short story by

Heinrich Böll (known as Bonn Diary in English, and occupying only

ten short pages in Böll’s collection Absent Without Leave). Thus

to recapitulate the plot in abbreviated form raises the same central

question that Straub poses; namely, what is necessary? For Karl-

heinz Stockhausen, who wrote Straub an enthusiastic letter after

seeing the film at Oberhausen in 1963, it is a film entirely without

ornamentation. On the other hand, story and film alike are motored

on nothing but the accumulation of details, and it is debatable just

how many of these are absolutely essential either to Böll or to Straub:

the latter omits, for example, a performance of a concerto for seven

drums given after the laying of the Academy’s cornerstone, which is

renamed the Hürlanger-Hiss Memorial Septet; and omitted from the

above synopsis are such details as the hero’s solipsistic dream of

encountering several memorials inscribed with his name, experienced

the night of his arrival in Bonn, and his remark in the narration that

he’d like to have an affair with Heffling’s wife, which is full of blatant

class overtones. But how much do we need to know about Machorka-

Muff’s odiousness and what it entails for enlightenment to register?

Straub has helpfully added a series of street placards (“To become old

and remain young is the hope of everyone’) and newspaper headlines

(“Will We Become Hammer or Anvil?”) to punctuate his walk through

Bonn and thereby underline both his psychology and the historical

context; here and elsewhere, pans from hero to urban or country

landscapes (or texts) and vice versa imply ideological as well as visual

continuities — the opening pan across a vista of Bonn at night, indeed,

has a rather Mabuse-like aspect. And the concentration and mainly

fast cutting serve to make each shot of the film a deadly little

‘monument’ to Machorka-Muff, like the row of these glimpsed in his

dream –- successive nails driven into the bland surface of his congested

myth. But to understand Straub’s precision with any clarity, a reading

of the Böll story is almost obligatory; otherwise, it is difficult to

assimilate the narrative details as rapidly as Straub dispenses with

them. Stockhausen’s very sensitive appraisal (reprinted in Richard

Roud’s book on Straub) treats the rhythms of the film musically, and

certainly this analogy carries some application; but it is possible that

the poetics of Ezra Pound, in his reduction of The Waste Land and some

of his own poems to their final states, may be equally useful to an

understanding of Straub’s approach to his material. The coolness of

Erich Kuby’s narration, the clean economy of the images, and the

marvelously abrupt ending — a sudden closing cadence with some

of the effect of a slammed door – all suggest a profusion of shots,

details and feelings forcibly hammered together to form a continuous,

dark and extremely packed surface. It is an appropriate enough

cornerstone for Straub to build his own Academy of Memories on,

in his subsequent films — laid here with a clipped decorum that

seems to take some of its staccato delivery (if not its ideology) from the

despised Machorka-Muff himself.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM