From the December 1, 2001 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

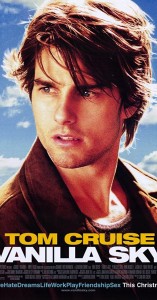

If you’ve ever wanted to bust Tom Cruise in the chops when he’s brandishing that self-infatuated, shit-eating grin — a desire even his hardiest fans must occasionally feel — then this is the movie for you. Cruise plays a Manhattan zillionaire who’s inherited a string of successful magazines; after screwing Cameron Diaz four times in one night (this is supposed to be the realistic part) he falls in love with another woman (Penelope Cruz) and winds up in an accident that leaves him disfigured like some character out of Victor Hugo. Director Cameron Crowe adapted the screenplay from Open Your Eyes (1997), a highly successful Spanish fantasy thriller by the talented Alejandro Amenabar, and while remaking a four-year-old film may seem silly, it perfectly fits the subject, remaking one’s life. Of course this version is much slicker, upgrading the original in some ways (if you prefer having everything spelled out) and overextending it in others (including the 130-minute running time); it reeks of unearned profundity, but I found it entertaining. With Kurt Russell, Jason Lee, and Noah Taylor; incidentally, Cruz played the same role in the Spanish film. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 1, 1989). — J.R.

James Benning’s 1988 feature, a substantial letdown after his Landscape Suicide, charts the filmmaker’s involvement with Lawrencia Bembenek, a former Milwaukee policewoman who, despite her persistent claims of innocenc, was convicted of killing her husband’s first wife in the early 80s. (Her case led to articles in Cosmopolitan and People, in part because of her achievements in prison reform while serving a life term.) Although several commentators have compared this film to The Thin Blue Line, there are many crucial differences: Benning’s friendship with his subject, a more extensive use of actors, and Benning’s background as an experimental filmmaker who generally uses narrative only in a skeletal and simplified form. (Bembenek’s own voice — like Benning’s — is used throughout, but an actress plays her on-screen.) Perhaps the principal problem lies in Benning’s failure to set down all the relevant facts of the case in an easily digestible form; he chooses, rather, to introduce them out of chronological sequence. In addition, his own semi-maudlin confessional letters, which are read offscreen (along with Bembenek’s terser ones), keep clouding the various issues raised. As in Benning’s earlier and better films, long takes that focus on midwestern landscapes are often employed, but without the sense of mystery and provocation that they usually have. Read more

From the April 1, 1996 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

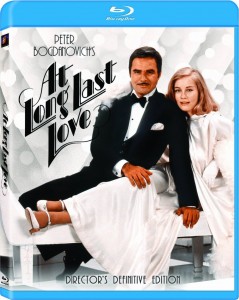

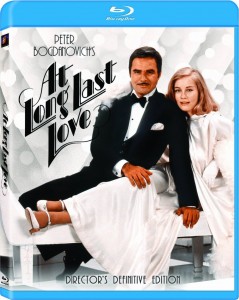

A daring experiment that failed (1975), this direct-sound musical set in the 30s — with Burt Reynolds, Cybill Shepherd, Madeline Kahn and Duilio Del Prete doing what they can (as singers and dancers) with and to Cole Porter — is probably Peter Bogdanovich’s worst film, but it’s perversely fascinating for its art-deco trimmings as well as its rather frightening coldness. I suspect that what makes it so hard to take is less its awkwardness as a musical (which could theoretically carry a certain charm) than its shocking sense of class snobbery and upper-class entitlement, which played a lesser role in Bogdanovich’s What’s Up, Doc? (1972) and which registers here as an eccentric misreading of Lubitsch. Ironically, this was made when Bogdanovich was at the height of his power as a studio director, before he developed the craft and sensitivity that characterize some of his later work. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 6, 1989). — J.R.

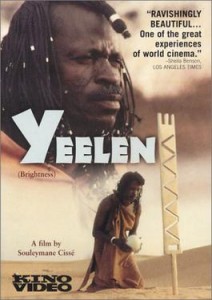

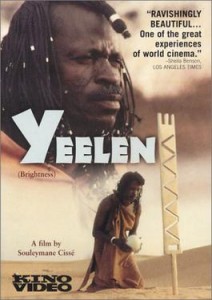

Souleymane Cisse’s extraordinarily beautiful and mesmerizing fantasy is set in the ancient Bambara culture of Mali (formerly French Sudan) long before it was invaded by Morocco in the 16th century. A young man (Issiaka Kane) sets out to discover the mysteries of nature (or komo, the science of the gods) with the help of his mother and uncle, but his jealous and spiteful father contrives to prevent him from deciphering the sacred rites and tries to kill him. In the course of a heroic and magical journey, the hero masters the Bambara initiation rites, takes over the throne, and ultimately confronts the magic of his father. Apart from creating a dense and exciting universe that should make George Lucas green with envy, Cisse has shot breathtaking images in Fujicolor and has accompanied his story with a spare, hypnotic, percussive score. Conceivably the greatest African film ever made, sublimely mixing the matter-of-fact with the uncanny, this wondrous work provides an ideal introduction to a filmmaker who, next to Ousmane Sembene, is probably Africa’s greatest director. Not to be missed. Winner of the jury prize at the 1987 Cannes Film Festival. (Film Center, Art Institute, Columbus Drive at Jackson, Friday, January 6, 7:30; Saturday, January 7, 4:00 and 7:30; and Sunday, Tuesday, and Thursday, January 8, 10, and 12, 6:00; 443-3737)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 10, 1989). — J.R.

The all-time best Rudy Vallee performance is as a gentle, puny millionaire named Hackensacker in this brilliant, simultaneously tender and scalding 1942 screwball comedy by Preston Sturges — one of the real gems in Sturges’s hyperproductive period at Paramount. Claudette Colbert, married to an ambitious but penniless architectural engineer (Joel McCrea), takes off for Florida and winds up getting wooed by Hackensacker. When McCrea shows up she persuades him to pose as her brother. Also on hand are such indelible Sturges creations as the Weenie King (Robert Dudley), the madly destructive Ale and Quail Club, Hackensacker’s acerbic sister (Mary Astor), her European boyfriend of obscure national origins (Sig Arno), and many others. Hackensacker may be the closest thing to a self-parody in the Sturges canon, but it’s informed with such wry wisdom and humor that it transcends its personal nature (as well as its reference to such tycoons as the Rockefellers). With William Demarest, Jack Norton, Franklin Pangborn, and Jimmy Conlin; not to be missed. This screening will be accompanied by a lecture by Virginia Keller. (Film Center, Art Institute, Columbus Drive at Jackson, Tuesday, February 14, 6:00, 443-3737)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 1, 1989). — J.R.

Writer Leonard Gershe, director Stanley Donen, and producer Roger Edens take on French existentialism in this colorful and sumptuous 1957 musical, set largely in Paris and starring Fred Astaire and Audrey Hepburn, with a dreamy Gershwin score. Although the anti-intellectualism gets thick in spots, the visuals are consistently stylish. Astaire is a fashion photographer (Richard Avedon supervised his photo sessions), Hepburn a Greenwich Village bookworm transformed into a model (clothes by Givenchy), and Kay Thompson plays their fashion editor. The film’s sophistication is compromised by the rather dumb plot, but some of the numbers — especially “Think Pink” and “Bonjour Paris” — are standouts. 103 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (November 22, 1994). — J.R.

Writer-director Ron Shelton’s fourth feature (Bull Durham, Blaze, and White Men Can’t Jump are the other three) is a shambles, but it’s such a potent and courageous wreck of a movie that it’s worth more than most successes. Only obliquely a sports story, and missing most of Shelton’s usual humor, this is a troubled portrait of an odious Ty Cobb, possibly the greatest of all baseball players, from the vantage point of the last year or so of his life. Based on the recollections of Al Stump, who ghosted Cobb’s self-serving and unreliable 1961 autobiography, the film fails to make either Cobb or Stump fully believable, despite a towering performance by Tommy Lee Jones as the former and a perfectly adequate one by Robert Wuhl as the latter. In part that’s because Shelton, hampered in his efforts to shift between the two characters’ points of view, is actually after bigger game: a critique of the American success ethic and the preference for legend over truth. (In many ways, the story has more in common with The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance than with any other sports biopic.) The sheer, dark unpleasantness of what emerges is such that at certain moments even Shelton backs away from it and tries to wring out a sentimental tear or two (along with a belated Freudian revelation). Read more

From the December 1, 1994 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

An exasperating demonstration of what’s wrong with contemporary Hollywood and what’s wrong with contemporary American election campaigns, pitched in the form of a cutesy romantic comedy that should set your teeth on edge. Loosely inspired by the well-publicized romance of Mary Matalin and James Carville during the 1992 presidential election, with Ron Underwood (City Slickers) directing a script by Robert King (Clean Slate), this throws together a Republican speechwriter (Michael Keaton) and a Democratic speechwriter (coproducer Geena Davis) during a senatorial campaign in New Mexico and watches their love blossom as they proceed to work competitively. The movie’s smart enough to offer a jaded portrait of the way such campaigns operate, but the hackneyed love story repeatedly relegates it to the back burner, and matters weren’t helped by test-market previews that led to a new and exceptionally stupid feel good ending. Ultimately, for all its fancy footwork, this movie winds up being even sicker than what it’s looking at. With Christopher Reeve, Bonnie Bedelia, Ernie Hudson, Charles Martin Smith, and Gailard Sartain (1994). (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 1, 1994). Perhaps my biggest error in this review is my assumption that all the leading characters in Metropolitan are male. — J.R.

The second comedy feature (1994) of writer-director Whit Stillman (Metropolitan), who shares with Eric Rohmer a talent for literate and witty dialogue and a fascination with photogenic young women but has a somewhat less confident sense of milieu and story construction. As in Metropolitan, the leading characters and principal source of amusement are wealthy, self-absorbed, and virtually interchangeable American males (in this case a salesman and his cousin, a naval officer), though here they’re transplanted to the Barcelona jet-set nightclub scene, where they explain to their girlfriends and each other (as well as to the audience) how misinformed the Spanish are about the U.S. Considering how successfully they seem to colonialize all the young Spanish women in sight, regarded by heroes and movie alike as obliging pieces of furniture, one subtext seems to be that Europeans are basically first-draft Americans hungrily awaiting stateside revision. Still, this is fairly amusing stuff — brittle, fresh, and impudent –if you can stomach all the upscale arrogance. With Taylor Nichols, Chris Eigeman, Tushka Bergen, Mira Sorvino, Pep Munne, and Hellena Schmied. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 20, 1994). — J.R.

Alan Parker’s flair for vulgar showmanship pays off in his funny, entertaining 1994 adaptation of T. Coraghessan Boyle’s novel. The movie’s set in 1907 in Michigan’s Battle Creek Sanitarium, which is presided over by pre-New Age guru Dr. John Harvey Kellogg (Anthony Hopkins). Health — the open sesame of the sucker’s purse, says a con man played by Michael Lerner, and while Parker’s satirical viewpoint encompasses this judgment and plenty of chicanery, it’s also sympathetic enough in the bargain to honor the sincerity of fanatics like Kellogg and many of his patients. Among the other leading characters are a dysfunctional married couple played by Bridget Fonda and Matthew Broderick who check into the sanitarium and wind up getting various forms of sex therapy (inadvertent and otherwise), Kellogg’s rebellious adopted son (Dana Carvey), and a young entrepreneur in town (John Cusack) who’s interested in becoming a breakfast cereal tycoon. The treatment of period is both fanciful and highly enjoyable, and if the story seems to run out of both ideas and energy before the end, it’s still an entertaining ride most of the way. With Colm Meaney, John Neville, Lara Flynn Boyle, Traci Lind, and Camryn Manheim. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (1990). — J.R.

A remarkable and beautiful 160-minute family saga by the great Taiwanese filmmaker Hou Hsiao-hsien (A Time to Live and a Time to Die, Dust in the Wind) that begins at the end of Japan’s 51-year colonial rule in Taiwan and ends in 1949, when mainland China becomes communist and Chiang Kai-shek’s government retreats to Taipei. Perceiving these historical upheavals through the varied lives of a single family, Hou again proves himself a master of long takes and complex framing, with a great talent for passionate (though elliptical and distanced) story telling. Given the diverse languages and dialects spoken here (including the language of a deaf-mute, rendered in intertitles), this is largely a meditation on communication itself. It is also one of the few masterworks of the recent contemporary cinema, and a film that deserves a lot more attention than the couple of screenings it’s getting locally; it’s depressing to think that even the best new Asian films usually can’t get distributed in this country (1989). (Film Center, Art Institute, Columbus Drive at Jackson, Saturday, June 23, 4:30, and Sunday, June 24, 6:00, 443-3737)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 1, 1996). — J.R.

Charles Burnett’s fifth feature (and the first he didn’t write), made for the Disney Channel in 1996. Adroitly scripted by coproducer Bill Cain from Gary Paulsen’s sketchy and rather lurid short novel for young adults, this is a powerful, skillful tale about one antebellum plantation slave (the title character, played by Carl Lumbly of To Sleep With Anger) teaching another slave (the narrator, a 12-year-old girl played by Allison Jones) how to read. As a parable about empowerment through reading this is at least as strong as Fahrenheit 451, and as a didactic fairy tale about the relationship between slavery and literacy it’s even stronger. In keeping with their Disney origins, Burnett delivers the story and drama in broad strokes, though he depicts even the white villains with humanity and some complexity (as in his only other film involving white as well as black characters, The Glass Shield). A wonderful, fully realized work — passionate, stirring, and beautiful. With Beau Bridges, Lorraine Toussaint, Bill Cobbs, and Kathleen York. 95 min. (JR)

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (November 1, 2000). — J.R.

Land Without Bread (1932), Luis Buñuel’s only documentary, examines the hopeless living conditions of an impoverished village in western Spain; Ramon Gieling’s 73-minute Dutch documentary The Prisoners of Buñuel reveals what the village’s people think of the film 60-odd years later, and while it’s hardly the last word on Buñuel, it does offer a thoughtful and provocative reflection on the intricate cross-purposes of life and art — not to mention accuracy and truth. One can’t necessarily believe everything the villagers say about the film, especially because some of them contradict one another. But conversely, to take Buñuel’s masterpiece entirely at face value would be to misread it: it’s a metaphysical statement more than anything else, and its offscreen narration mocks the touristic documentary in countless ways. It’s impossible to evaluate The Prisoners of Buñuel adequately if you haven’t seen Land Without Bread, and Gieling, who jokingly draws attention to the way portions of his own documentary are staged, seems well aware of the problem. (Several extracts appear when he screens the film in the village square, but hardly enough to allow for any final verdict.) Unfortunately this U.S. premiere, which Gieling will attend, doesn’t include Land Without Bread on the program, but Facets Multimedia Center will show it on Friday, November 17, as part of a Buñuel retrospective. Read more

This review, originally published in August 3, 1990 Chicago Reader, was one of my first sustained efforts to write about the employment of jazz in movies. The movie isn’t as good or as entertaining as Lee’s latest messy Brechtian musical, Chiraq, although the latter film suggests once again that he still doesn’t have a clear sense of how to use music. — J.R.

MO’ BETTER BLUES ** (Worth seeing)

Directed and written by Spike Lee

With Denzel Washington, Lee, Wesley Snipes, Giancarlo Esposito, Robin Harris, Joie Lee, Cynda Williams, Bill Nunn, Dick Anthony Williams, and John Turturro.

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

First the good news: strictly as an exercise de style, Spike Lee’s fourth joint is in certain respects the liveliest and jazziest piece of filmmaking he’s turned out yet. From the arty close-ups behind the opening credits of — and liquid pans past, and dissolves between –- trumpet, lips, and lovers’ grasping hands in blue, yellow, amber, and green to the matching semicircular crane shots that frame the story, this is a movie cooking with ideas about filmmaking. Bringing back a good many of the featured players in Do the Right Thing, and introducing to the Spike Lee stable the highly talented Denzel Washington, Cynda Williams, Wesley Snipes, and Dick Anthony Williams (among others), it’s a movie bursting with personality and actorly energy as well. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 1, 1990). — J.R.

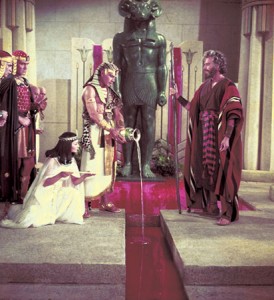

With a running time of nearly four hours, Cecil B. De Mille’s last feature and most extravagant blockbuster is full of the absurdities and vulgarities one expects, but it isn’t boring for a minute. Although it’s inferior in some respects to De Mille’s 1923 picture of the same title (which used the story of Moses as an extended prologue to a contemporary tale) and some of the special effects look less plausible now than they did in 1956, the color is ravishing, and De Mille’s form of showmanship, which includes a personal introduction and his own narration, never falters. Simultaneously ludicrous and splendid, this is an epic driven by the sort of personal conviction one almost never finds in more recent Hollywood monoliths. With Charlton Heston, Yul Brynner, Anne Baxter, Edward G. Robinson, Yvonne De Carlo, Debra Paget, John Derek, Cedric Hardwicke, H.B. Warner, Judith Anderson, Vincent Price, John Carradine, and many other familiar faces, including Woody Strode as the king of Ethiopia. 220 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more