From the Chicago Reader (April 1, 1990). — J.R.

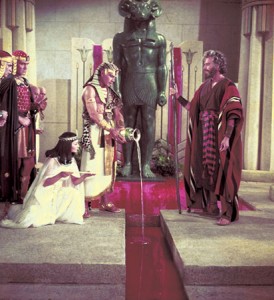

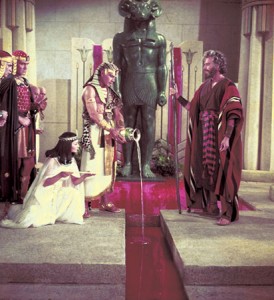

With a running time of nearly four hours, Cecil B. De Mille’s last feature and most extravagant blockbuster is full of the absurdities and vulgarities one expects, but it isn’t boring for a minute. Although it’s inferior in some respects to De Mille’s 1923 picture of the same title (which used the story of Moses as an extended prologue to a contemporary tale) and some of the special effects look less plausible now than they did in 1956, the color is ravishing, and De Mille’s form of showmanship, which includes a personal introduction and his own narration, never falters. Simultaneously ludicrous and splendid, this is an epic driven by the sort of personal conviction one almost never finds in more recent Hollywood monoliths. With Charlton Heston, Yul Brynner, Anne Baxter, Edward G. Robinson, Yvonne De Carlo, Debra Paget, John Derek, Cedric Hardwicke, H.B. Warner, Judith Anderson, Vincent Price, John Carradine, and many other familiar faces, including Woody Strode as the king of Ethiopia. 220 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 1, 1989). This lovely and sexy film is available on Twilight Time, with lots of extras (including deleted scenes and two separate audio commentaries). — J.R.

Real-life brothers Jeff and Beau Bridges play Jack and Frank Baker, a second-rate cocktail-lounge piano duo with staying power who hire sexy vocalist Susie Diamond (Michelle Pfeiffer) to strengthen their act, in the impressive 1989 directorial debut of screenwriter Steve Kloves (Racing With the Moon), who also wrote the script. Frank is the square brother who handles the business; he’s married, with kids, and not very musically inspired. Jack is remote, relatively irresponsible, and gifted; he plays jazz in his spare time and sounds like a leaner version of Bill Evans (his piano solos are dubbed, for the most part expertly, by Dave Grusin, the film’s music director). Susie is a former call girl who brings some soul to the group, as well as some problems when she and Jack develop a mutual attraction. This pared-away comedy-drama, which concentrates exclusively on the three characters, has plenty of old-fashioned virtues: deft acting, a nice sense of scale that makes the drama agreeably life-size, a good use of Seattle locations, fluid camera work (by Michael Ballhaus), a kind of burnished romanticism about the music, and a genuine feeling for the characters and their various means of coping. Read more

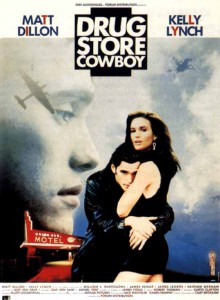

From the Chicago Reader (October 1, 1989). — J.R.

This amiable, no-nonsense account of a quartet of Portland, Oregon, junkies in 1971 fully lives up to the promise of Mala Noche, director Gus Van Sant’s previous feature. Adapted by Van Sant and Daniel Yost from an unpublished autobiographical novel by James Fogle, this 1989 feature has the kind of stylistic conviction that immediately wins one over; it conveys something of a junkie’s inner life with its editing rhythms, unorthodox use of sudden close-ups, hallucinatory passages, and Matt Dillon’s offscreen narration, and it documents the outer necessities of the lifestyle (including many drugstore robberies and changes of address). The characters are all quirky and life-size (the Dillon character’s superstitiousness is one of the principal motors of the plot, and the story’s outcome doesn’t prove him wrong), and like Bill Forsyth’s handling of the burglaries in Breaking In, Van Sant’s treatment of drugs is refreshingly free of either moralizing or romanticizing. It’s one indication of his ease and assurance that he successfully integrates the persona of William S. Burroughs into a fiction film: all the actors are used expertly, but it’s Burroughs, cropping up near the end, who articulates the film’s sociopolitical moral in a contemporary context. Read more

From the March 1, 1988 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Based on a play that constitutes part two of Neil Simon’s autobiographical trilogy, concerned with the experiences of the hero (Matthew Broderick) at boot camp in Biloxi, Mississippi, in 1943, this is an engaging, well-crafted comedy that receives very able direction from Mike Nichols. The period decor and details are nicely handled (apart from the silly decision to adapt clips from Buck Privates and Movietone News to the ‘Scope format, yielding an unnecessary anachronism), and while most of the characters are fairly standard types — sadistic drill sergeant (Christopher Walken), Jewish intellectual (Corey Parker), Polish lout (Matt Mulhern), raunchy prostitute (Park Overall), sophisticated girlfriend (Penelope Ann Miller) — the actors give them their best shot, including the somewhat miscast Walken. The nostalgic visual style of the film, successfully modeled on Norman Rockwell by production designer Paul Sylbert and cinematographer Bill Butler, is especially fetching, and the somewhat Woody Allen-ish offscreen narration shows Simon at his best. Perhaps this movie isn’t as wise or as profound as Simon wants it to be, but it is certainly a cut above sitcom complacency, and packed with wit and charm (1988). (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 8, 1996). — J.R.

One swell reason for seeing this fresh Americanized remake of La cage aux folles — the 1978 French farce about a middle-aged gay couple — written by Elaine May for her old improv partner, producer-director Mike Nichols, and costarring Robin Williams and Nathan Lane as the couple — is its hilarious depiction of Pat Buchanan as played by Gene Hackman, which implies, among other things, that only a drag queen could adequately fulfill Buchanan’s dream of ideal womanhood. More specifically, the son (Dan Futterman) of the proprietor (Williams) of a Florida nightclub with a drag show called “The Birdcage” becomes engaged to the daughter (Calista Flockhart) of an ultraconservative senator (Hackman) who wants to visit his future in-laws, leading to frantic preparations for a dinner party at which the proprietor’s drag-queen partner winds up playing the boy’s mother. (Hackman’s wife, incidentally, is played by Dianne Wiest.) This isn’t the supreme masterpiece it might have been, but Nichols’s direction is very polished and some of the lines and details are awfully funny.

— Jonathan Rosenbaum

Read more

Read more

From the Los Angeles Times’ Calendar, June 14, 1987. For readers who might wonder how I could have ever gotten such an assignment, I should point out that in this period, the Los Angeles Times was running anti-Ishtar articles virtually every day over several weeks, so I assume that my contrary position must have had some interest for them strictly as a novelty. This piece is reprinted in my most recent collection, Cinematic Encounters 2: Portraits and Polemics (2019). — J.R.

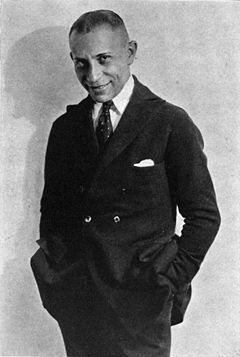

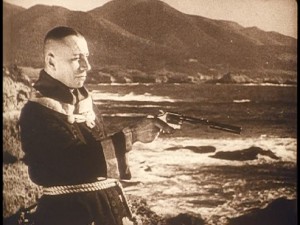

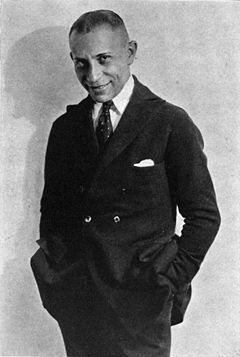

In all of Elaine May’s films, one encounters a will to power, a witty genius for subversion and caricature, and a dark, corrosive vision that recalls the example of Eric von Stroheim. The legendary Austrian-born director who started out, like May, as an aggressive actor (“The Man You Love to Hate”), Stroheim the film maker was known throughoutthe ’20s for his intransigence and extravagance — what one studio head termed his “footage fetish’.

The thematic and stylistic parallels between May and Stroheim are equally striking. Broadly speaking, “A New Leaf” is her “Blind Husbands” — a bold first film about ferocious, cynical flirtation, with the writer-director in the lead part. The Miami of “The Heartbreak Kid matches the Monte Carlo of “Foolish Wives”; the squalor and hysteria of “Mikey and Nicky” hark back to “Greed.” Read more