From the June 11, 1999 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

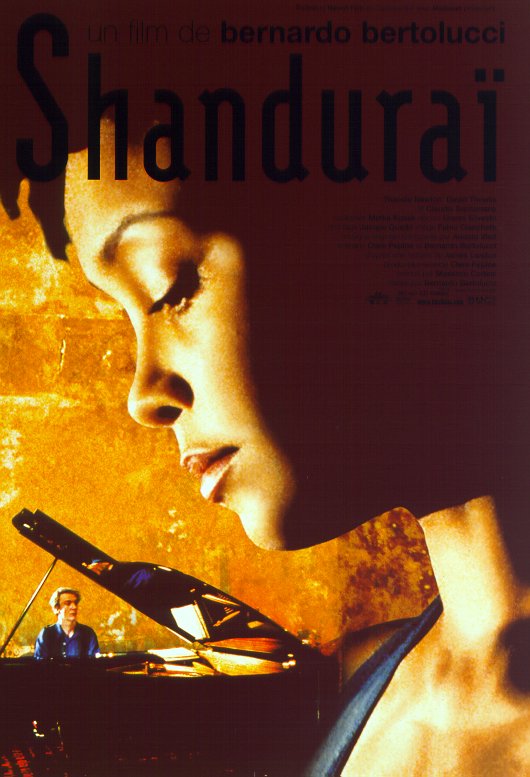

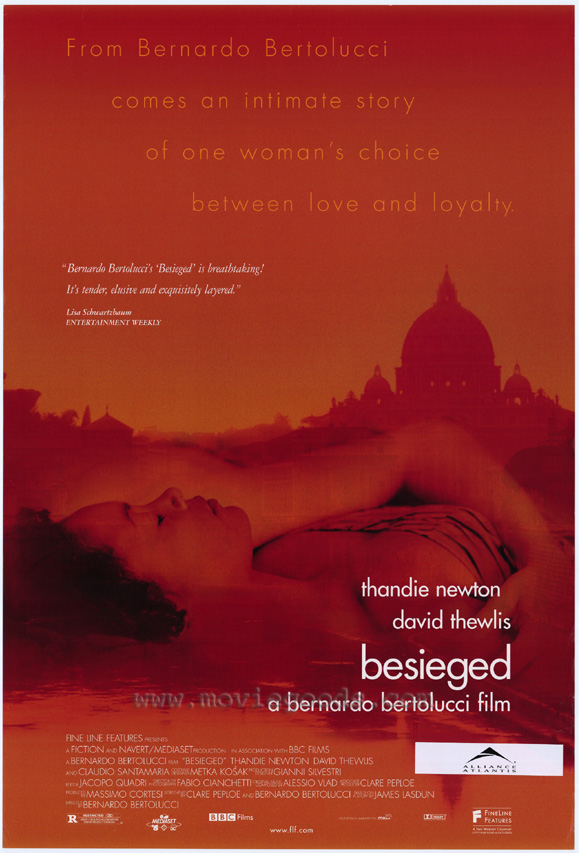

Besieged

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by Bernardo Bertolucci

Written by Bertolucci and Clare Peploe

With Thandie Newton, David Thewlis, and Claudio Santamaria.

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

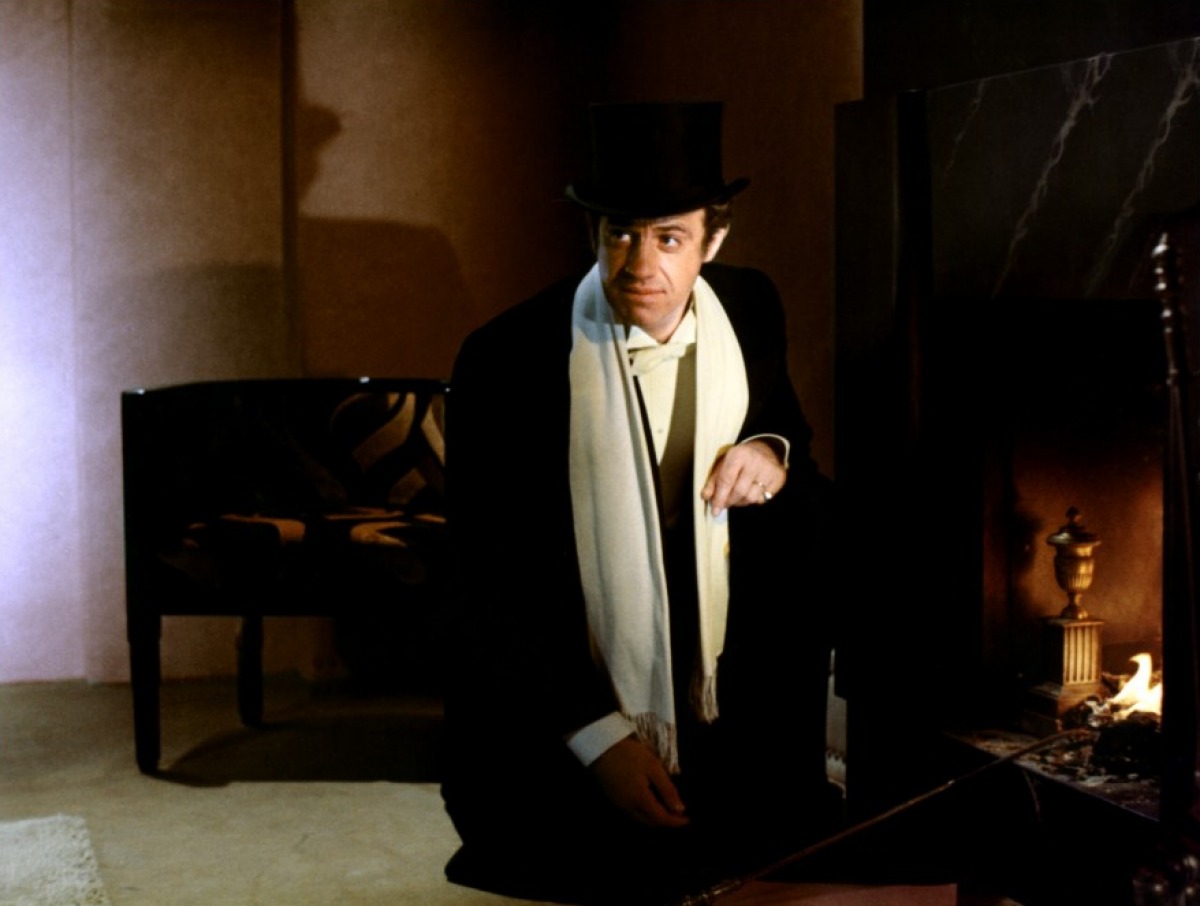

Many times over the past three decades I’ve been close to giving up on Bernardo Bertolucci. The rapturous lift of his second feature, Before the Revolution (1964), promised more than he seemed prepared to deliver with the eclectic Partner (1968). Yet it was The Spider’s Stratagem (1970) rather than The Conformist (made just afterward and released the same year) that renewed my faith in his talent. Both movies, like Before the Revolution and Partner, were the flamboyant expressions of a guilt-ridden leftist, a spoiled rich kid with a baroque imagination and a social conscience that yielded dark and decadent ideas about privilege and guiltless fancies about sex. Where they differed for me was in the degree to which The Conformist succumbed to fashionable embroidery, a stylishness that took the place of style.

It was the relatively big budget The Conformist, an adaptation of an Alberto Moravia novel, that made Bertolucci’s name in the world market and so influenced American movies that Coppola’s Godfather trilogy would have been inconceivable without it. Read more