From Film Comment (March-April 1974). — J.R.

December 7: To enter the sound stage at Epinay-sur-Seine, a Parisian suburb where Alain Resnais is working on his new film about Alexandre Stavisky, you have to go through a heavy door that resembles the entrance to a bank vault, where you’re promptly greeted by Alexandre, a friendly dog who seems to be serving as the crew’s mascot (a younger dog named Sacha figures in the cast). Continuing past Alexandre, you weave your way through a labyrinth of construction that eventually resolves itself into a gargantuan neo-Lubitsch set comprising Stavisky’s office complex — a rather awesome 1933 décor the size of a country house that took forty people a month to build, even though it’ll only be used for a relatively short part of the film.

It’s the kind of set you can get lost in, with multiple exits and three separate stairways leading off of a giant central conference room with golden chandeliers, a large semi-circular table, light-green walls, tall windows with pink drapes, and no ceiling; a set where long hallways on the second landing go past doors that open on nothing, and members of the lighting crew move about in obscure corners carrying equipment and muttering to themselves. Another, equally large set of Stavisky’s suite at Hotel Claridge, which has already been dismantled to make room for this one, will figure more prominently in the film, but Resnais explains to me that only about a quarter of the footage will be studio-shot.

“Actually, if I had the choice and it weren’t for economical reasons, I’d shoot everything in the studio.” Resnais is sitting across from me at a desk in a glassed-in office that occupies one corner of the set, with 1933 calendars (including a calendrier memento marked for various appointments), a period telephone, ink well and filing cabinet, and similar accoutrements that make my cassette recorder appear like something of an anachronism. “It’s easier to control things in the studio. To use locations you need to get permission from various authorities, and we’ve been refused in a lot of cases. We don’t always have to use real décors, but when we do — such as at the Théâtre Mogador — we have to post-synchronize, which means additional work, and is regrettable besides.”

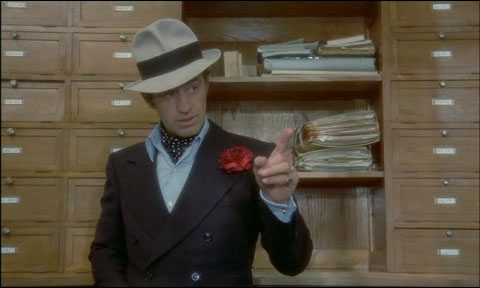

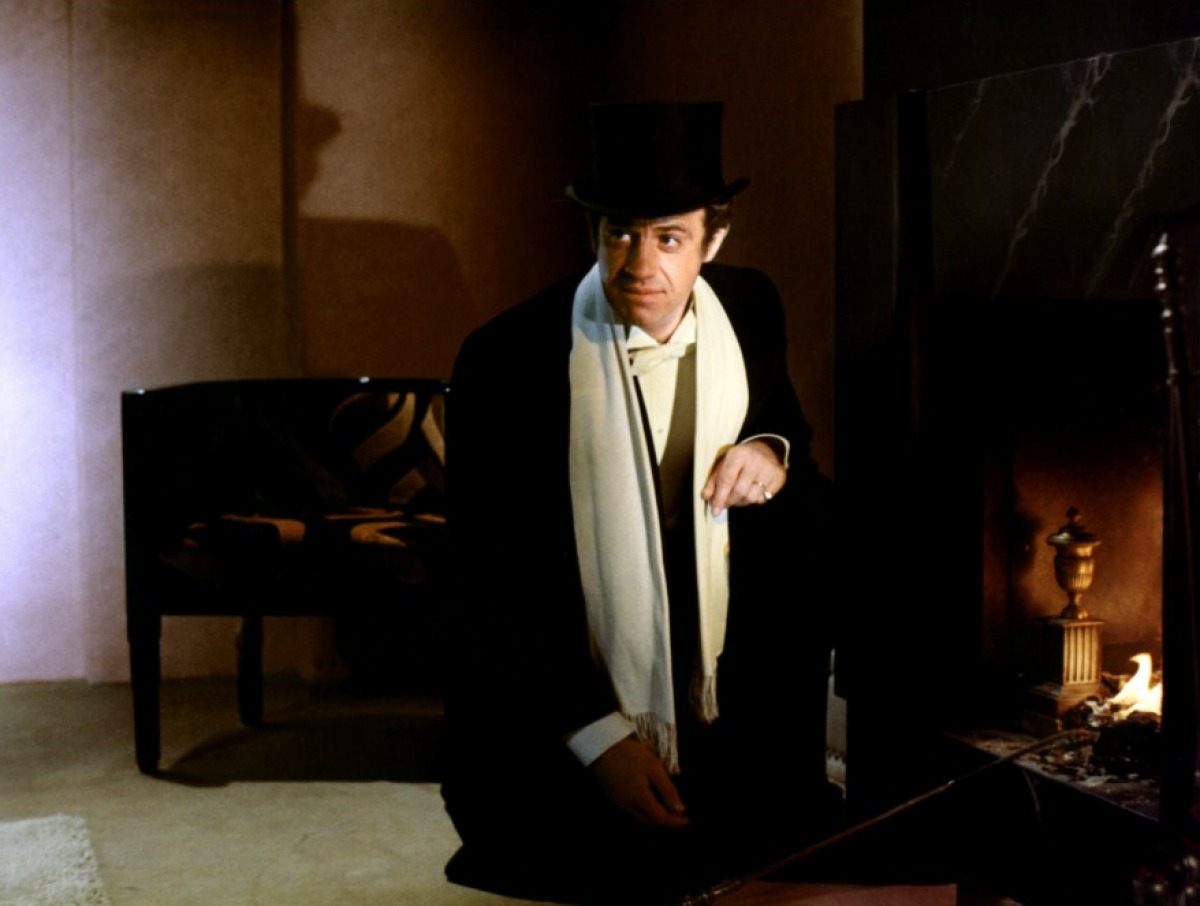

Flashback: Théâtre Mogador, November 13. I watch Resnais shooting a brief scene on the stage. Jean-Paul Belmondo, who plays Stavisky — the celebrated high-finance crook whose intrigues toppled two successive French ministries in the 1930’s — is crossing the stage with Silvia Badesco, an actress in a minor part, while Sacha Vierny — Resnais’s cameraman on all of his features to date, excepting JE T’AIME, JE T’AIME — tracks along with them. A few fairly clean takes, and then the crew breaks for lunch; Belmondo, who’s financing 80% of the film, clowns around, groans “Bordell“, manufactures a belch, and departs with his entourage. The attaché de presse fills me in on a few details: Jorge Semprun wrote the script with Resnais earlier this year, the shooting started on October first and is expected to end in January.

Another flashback: Théâtre Mogador, November 22. Today a sequence is being shot in the lobby — one involving more actors (including Charles Boyer) and more complicated lighting problems. Miraculously, Resnais seems to remain a model of serenity as he lumbers with the cast and crew through thirteen takes of a single shot. The camera doesn’t move this time, but many things can go wrong in the shot, and several of them do. Belmondo holds a glass of champagne at the bar while he delivers an angry burst of dialogue to another actor at a table in the right foreground. From one take to the next, Belmondo’s voice and gestures become progressively more animated and violent, so that each time he seems to spill more champagne with swipes of his hand.

Back at the studio. I ask Resnais, “What do you think the formal aspects of the film will be?”

“It’s difficult to say, because it’s not a question that I pose myself very much in advance. When the film’s finished, one can take everything into account. Right now I don’t perceive exactly the form it’ll take. All I can say is that Jorge Semprun and I are trying to work with a construction that’s very nonchalant, ‘carefree’ — a construction where the episodes in the film follow each other because of a phrase spoken by a character, a detail in the décor, or a gesture, which all at once leads to another fragment that finally brings one back to the central intrigue. It’ll be a very free sort of movement. We’re trying to make it a film without a great deal of rigor — not lazy, but let’s say ‘free and easy’.”

“I’m intrigued that you’re using a musical score by Stephen Sondheim. Will this be like music of the period?”

“No — or it won’t be precisely that, in any case. What I like about Sondheim is a particular effect he’s been able to convey over the past ten years. His music can begin with a feeling of freedom, facility and pleasure and then suddenly, right in the middle of the sugar, your teeth sink into a bitter almond, and it becomes something painful. I don’t know whether you’ve seen Sondheim’s musical Company, but that begins as a comedy and at the end it’s absolutely tragic. And I believe that if we succeed in our film, it will frequently unfold like a comedy with death and pain in the middle of it. There’s a relationship between that and what I’m looking for in Sondheim’s music — a mood that’s pretty and nice and at the same time has a lot of aggressiveness. I like the way he can do that melodically — include both things in the same melodic phrase.”

“How will you work together?”

“I think I’ll want to work with him the same way I’ve previously worked with composers. He’ll come to Paris once I have a rough cut. We’ll look at it and talk about it, then we’ll go into the editing studio and work on it bit by bit, in relation to the story, dialogue, and everything else.”

“Is this the most expensive film you’ve done so far?”

“Yes, it’s the largest budget I’ve ever had.”

“Does this have any disadvantages as far as working conditions are concerned — freedom of movement, the number of people involved, and so on?”

“No, there’s no difference. But this is the first costume film I’ve directed, and a good third of the budget has to go toward dressing all the actors and even all the extras. If we have to shoot on the street, we need to clear the traffic first and bring in cars of the period — that alone costs about 100,000 francs. But I feel I’m working under my normal conditions.”

“How much of the film is worked out in advance? Have you been adding to or changing the script much as you go along?”

“In this case, there wasn’t quite enough time to complete the script before the shooting began, so we’ve been continuing to make certain changes in the structure, shortening certain scenes as we go along. We haven’t been changing more than 20% of the original script. Of course, one always likes to prepare as much as possible before beginning to shoot, but sometimes we have to modify a little as we go.”

“Do you ever work like Hitchcock, by sketching shots in advance?”

“No — ” (a little smile) ” — because I can’t draw. But like everybody, I do make some rough sketches, and can imagine pretty well what it will look like. I do try to design the film pretty much beforehand.”

Flash-forward: I wander around the unoccupied parts of the set while Resnais and the crew prepare a shot in the big conference room. It’s fun to encounter various Belasco-like details — all the 1933 calendars set on January Ist (a date occurring somewhere between the discovery of Stavisky’s fraud and his death in Chamonix), a glimpse from the ground floor of a bookshelf filled with leather-bound volumes visible through a window on the third landing (on closer inspection, it isn’t a room at all), a great many old-style typewriters and rubber stamps and wooden cabinets. Occasional anachronisms are enjoyable too: an unobtrusive 1962 calendar lying on one of the desks, a period coat-rack that is presently being used by the crew. In the conference room, Resnais lines up a shot with Vierny — he invariably looks through his viewfinder and the lens for every shot — while a crew member briefly stands in for Belmondo and a flood of artificial sunlight comes through one of the high windows.

Flashback: in my apartment on the phone, November 13. Jorge Semprun is explaining to me that the construction of the film will be simple and essentially chronological — no flashbacks, and only one flash-forward.

Back at the studio: I’m asking Resnais about some of his unrealized projects, apart from the enternal Harry Dickson — past and future dreams:

(1) A script about the Marquis de Sade written by Richard Seaver, who’s translated many works of Sade into English. Resnais visited a lot of places where Sade lived and took photographs. The script was done in English for various reasons — to create a certain “distance,” the restraints of French censorship at the time. Now that the same restraints no longer exist, Resnais feels that the potential shock value of the project has been decreased.

(2) A script by Stan Lee. I was under the false impression that this was based on Lee’s comic book “Spiderman,” but Resnais explains it is something quite different, then goes on to ruminate about the filmic possibilities of Spiderman: “It’s quite difficult to resolve the problem, because I find that the super-hero — the god or demi-god — is so hard to embody in films. It’s so successful in the comic book form that I don’t know how the cinema could complete with that kind of richness. In this case, you have a super-hero with a lot of misfortunes, who comes down with colds and flunks his exams and takes bad photos, a character with a very fragile personality. Perhaps he could be used in a film if you adopted a particular bias…”

(3) “A long documentary with Henri Laborit, a French biologist, which would deal with the brain, the mechanism of thought — but that’s such a difficult project, I don’t know if it’ll happen . . .” [2011: This eventually developed into MON ONCLE D’AMERIQUE.]

“The problem with the Seaver and Lee projects are the same: they each cost over a million dollars, which is the maximum I can currently ask for to make a film. Frankly, I haven’t given up hope, but at this point, with the current film still unfinished, it’s really difficult to know…”

One more flash-forward: Resnais is directing a shot on the second landing of the office complex that has the particular advantage of revealing the entire width and over half the length of the set. No dialogue, just Belmondo walking — through a door and down a hallway, a right turn, down another hallway, then down the stairs into the conference room. The camera is stationed across from the stairway, and pivots back and around just as Belmondo approaches so that it can continue to follow his progress. All the camera movements that I’ve watched during the shooting appear to be executed with a kind of elation. There is really no way to describe Resnais at work without resorting to that Hemingway chestnut, “grace under pressure.”

Back to the interview: “Of your previous films,” I ask Resnais, “is there one in particular that satisfied you the most?”

“No, unfortunately. I’ve made too few films. If I’d made ten or fifteen, I think that then perhaps I could have a favorite. But since I’ve made so few, it’s too difficult to make a choice.”

“Do you still go to films often?”

“Yes. Not as often as Truffaut or Rivette or Chabrol. I see about a hundred a year.”

“Are there any that you’ve seen within the past year that you’ve been especially impressed by?”

“Yes — they’re very well-known films. I like to go see films in real movie theaters, not in private screenings. Some recent films that have particularly impressed me are familiar ones — Fellini’s ROMA, Bunuel’s LE CHARME DISCRET DE LA BOURGOISIE (of course!); and Truffaut’s LA NUIT AMÉRICAINE amused me very much. I don’t have a `secret’ film.”

“Does your film have a final title yet? Originally it was reported as L’EMPIRE D’ALEXANDRE, then as STAVISKY. . . ”

“No — we hope to have one by the time it’s finished, but at the moment we’re still looking. It’s important that it doesn’t give the impression of being a documentary on the Stavisky Affair, because that would deceive people. We want to alert people to the legendary, ‘serial’ side of Stavisky, as opposed to the reality.”

“Apropos of serials, do you think the film will have a Feuillade aspect?”

“Well, I didn’t know that. But I did three shots last week, and broke out laughing when I discovered that I’d virtually redone a shot from the last reel of Louis Feuillade’s LES VAMPIRES. It was completely unconscious — something that came from the cameraman and me that wasn’t even evident until we saw the rushes. But it wasn’t intentional!”