From the Chicago Reader (July 6, 1990). — J.R.

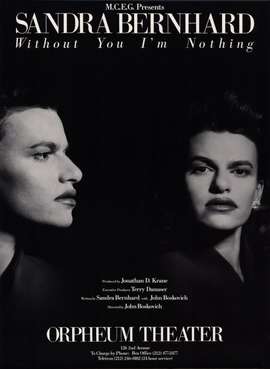

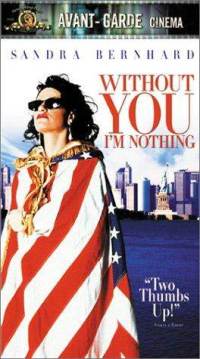

WITHOUT YOU I’M NOTHING

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by John Boskovich

Written by Sandra Bernhard and Boskovich

With Sandra Bernhard, John Doe, Steve Antin, Lu Leonard, Ken Foree, and Cynthia Bailey.

Once upon a time, before postmodernism came along, art tended to be about reality and the world — not always, to be sure, but more often than today. Then a group of professors and hucksters (as well as huckster-professors) got together and said, “What are reality and the world except particular versions of what we used to call art? And anyway what do we know about the world apart from what we see on TV, which is a form of popular art? The subject of art has always been other art, and postmodernism — unlike modernism, which is old hat by now, and all art prior to modernism, which is even older hat — is up-to-date art about other art. And what’s up-to-date is what sells.” Or words to that effect.

If capitalism is devoted in part to developing new markets, and advertising and journalism are devoted to promoting them, then postmodernist criticism is a means of backing up that promotion with hard intellectual currency. Broadly speaking, there have been two major ways of developing the film-criticism market outside the university over the past 30 years: turning junk into art, which has mainly been done with auteurism, and turning art into junk, which is basically the business of postmodernism.

If you believe, as I firmly do, that Marilyn Monroe subverts her typecasting and gives a Brechtian performance in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes — a portrait of a predator knowingly using her power — then you may be less than infatuated with Madonna’s postmodernist appropriation of Monroe’s sexpot image, an appropriation that peels away all of the Brechtian irony and commentary to give us a sexpot pure and simple, or at least a sexpot that’s purer and simpler than Monroe’s Lorelei Lee. (One could argue in defense of Madonna that she, unlike Monroe, is in full control of her own image — a position that might be easier to sustain regarding one of her videos than regarding Dick Tracy‘s peekaboo editing, which seems more in line with the puritanical taste of someone like Jesse Helms. But compare Monroe’s performance as Lorelei Lee with anything in the Madonna canon before you leap to conclusions.)

If you find that supposedly subversive performance artists such as Laurie Anderson and Spalding Gray often turn out to be soothing rather than disturbing — titillating the mind and senses much as music videos do, without putting one on the spot about anything — then you’ll agree it’s entirely possible that here too the built-in narcosis of postmodernism may be responsible, a kind of self-satisfied stupor that seems to imply three things at once: (1) if it works, it’s art; (2) if it fails, it’s politics; and (3) if it sells, it works.

So how can an assault on show biz and slickness be an example of show biz at its slickest? How can a work of provocation be packaged so skillfully that provocation becomes an overall impression conveyed by the work rather than an integral part of it? How does one construct a confrontational movie that never actually confronts the audience? Or how, to be more specific, does one present a “one-woman show” with 32 other performers, not counting 26 on-screen and 33 offscreen musicians? Sandra Bernhard’s Without You I’m Nothing, a veritable bible of postmodernism, provides a few fascinating clues.

The camera pivots around a harpsichord player dressed like Mozart, then pans over to an adjacent piano player as the credits come on. There’s a cut to Bernhard applying finishing touches to her makeup in front of a dressing-room mirror; she turns to the camera and begins, “You know, I have one of those hard-to-believe faces. It’s sensual, it’s sexual . . .”

Eventually there’s a cut to a woman identified as Ingrid Horn, Bernhard’s “personal manager” (actually an actress, Lu Leonard), who explains that after Sandra’s success with her off-Broadway show, she needed to be brought back to earth, back to her “roots.” So Horn brought Sandra back to Los Angeles to one of the “upscale dinner clubs” where she made her start, the Parisian Room.

The scene shifts to a group of black musicians passing around a joint. When Bernhard’s act begins, she’s wearing a fancy African getup and launches into a Nina Simone song, “Four Women,” that begins, “My skin is black, my arms are long, my hair is woolly.” Her audience is primarily black and either unresponsive or more visibly unsympathetic; there’s a cut to a disconcerted black woman at one of the front tables to drive the point home.

A black emcee (Ken Foree) with a joint comes up to the mike after the song and formally introduces her. Then he introduces another performer, “Shoshanna” (Denise Vlasis), a stripper made up to resemble Madonna, who goes into her Madonna-like number, during which there’s the first of the film’s many cuts to an attractive black woman (Cynthia Bailey) walking outside in an unidentified location. (The press materials refer to her as Bernhard’s alter ego, though I suppose she also can read as her lover; in any case she reeks of the kind of significance accorded to muses in Fellini films.)

The camera returns to the Parisian Room, to Bernhard singing an Israeli folk song, then reminiscing about the New York World’s Fair in the mid-60s, her childhood in Flint, Michigan, her parents’ divorce five years ago, her father’s remarriage to a gentile, her three older brothers. This finally leads into a series of fantasies about being gentile that are centered around Christmas carols, with diverse black and white musicians and fellow carolers appearing to accompany her and snow falling onstage . . .

I’ve left out some of the funnier and stranger details in this opening (e.g., the lethal metal mittens worn by the carolers), but my main point is to indicate the overall spread of the material. One can easily glean from this summary what’s “provocative” about the material — the unsympathetic black audience is especially interesting as a distancing device — though it must be added that, like much postmodernist art, Without You I’m Nothing has its own built-in ad copy: that is, the fact that it’s supposed to be provocative is already virtually part of the text, which means that it isn’t really all that provocative. Like The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover and Twin Peaks, part of its appeal is that it’s supposed to be shocking and daring to other people — not to the people watching it, who are implicitly invited to feel superior to these unseen philistines.

I haven’t followed Bernhard on that postmodernist outpost Late Night With David Letterman, and while I’ve made some stabs at reading her recent nonbook Confessions of a Pretty Lady, I haven’t gotten very far with it. But I deeply and sincerely treasure her performance as a crazed TV fan in Scorsese’s The King of Comedy, and wish that she’d taken a few lessons from that remarkable film about how to put postmodernist tactics to more lethal use — such as the technique of aping the bland images and banter of TV talk shows to suggest their murderous and hidden underside. (Martin Scorsese may not brag about having any political agendas, as Bernhard does, but at least he has the instincts of an artist — and a modernist artist at that — to tease out all the implications inherent in the material.)

I don’t want to suggest that Bernhard and her cowriter and director John Boskovich don’t put on a very well mounted, professional show that’s lots of fun and very easy to take. From a purist standpoint one might criticize some of the abrupt cuts to extreme close-ups and other pushy or simply arty attention-getting devices in the mise en scene, but I can’t say that I was ever bored. Bernhard’s monologues are generally packed with savvy: brand names that clue in the audience about how hip and knowing they are (or aren’t); hand gestures that mock the phoniness of various show-biz conventions; sudden comic swerves in tone or emotional emphasis (which can be musical as well as verbal, as in an instantaneous switch from a country-western ballad to a scat chorus of “On Broadway,” or the transition from classical to pop behind the credits); satiric nuances that speedily flash by (as in Bernhard’s account of buying an Indian blanket at an auction of Andy Warhol’s effects at Sotheby’s).

What’s missing is anything that registers as personal risk or investment; the sustained tone of facetiousness and the shallowness that comes with it rule out any moment or emotion that doesn’t appear between quotation marks (a hallmark of postmodernism). Despite the autobiographical stretches, it’s well-nigh impossible to know whether Bernhard is baring some part of her soul or putting us on (or situating herself somewhere in between these possibilities), and it’s often almost as difficult to care.

One never has any such doubts watching Richard Pryor–Live in Concert (1979), a key document of our era, and to my mind the best stand-up “concert” film ever made. The sheer physicality of Pryor’s self-exposure guarantees that he is putting himself on the line at every second — and implicating the audience in this process in every way possible. Bernhard, by contrast, asks and even obliges us to reflect mainly on how hip we are: she is out to toy with us a little perhaps, but not really to frighten or challenge us. When she wraps herself in an American flag toward the end, she may not be entertaining the Barbara Bush crowd, but I don’t imagine that those folks are hanging out at the Fine Arts anyway.

By the same token, it’s hard to determine whether her imitations of black performers like Nina Simone and Diana Ross qualify as “tributes” — which is the way the press materials describe them — or as contemptuous mockeries. In classic postmodernist fashion, they probably qualify to some extent as both (which is another way of saying that they qualify to some extent as neither). They remind me of the jokey Jewish literature professor I knew in the 60s who used to go on antiwar marches with a placard reading, “No Vietnamese ever called me nigger.” I suppose he had a point to make, but it isn’t a very enduring one.