Here are two recent valuable acquisitions I’ve made via French Amazon — Antoine de Baecques’s 940-page biography of Jean-Luc Godard, the first one in French (after two in English, by Colin MacCabe and Richard Brody), published by Bernard Grasset, and Godard’s 107-page “book” version of (or companion to) his recent Film Socialisme, published by P.O.L, his usual publisher, and subtitled Dialogues avec visages auteurs (literally, “Dialogues with faces authors”).

It’s far too early to make any sweeping judgments about either book — which would be presumptuous for me to attempt to do at any point, given my less than perfect French — but a few first impressions are in order. De Baecque’s biography is full of interesting details, in particular ones drawn from formerly unavailable or unfamiliar documents, e.g., a letter from Pasolini to Godard about La chinoise, and, roughly two decades later, a letter from Godard to Norman Mailer about some of his plans for King Lear. But it also appears that De Baecque can’t be trusted very much when it comes to his handling of American criticism about Godard. A minor complaint (which I hope doesn’t sound churlish, given how flattering he is to me elsewhere in this book): he claims, based on the French translation of my autobiographical Moving Places, that I spent “half my time in Paris between 1966 and 1968” seeing or reseeing Godard films on drugs; but in fact, apart from a couple of summer visits to Paris during this period (during which my Godard viewing goes unmentioned), my extended sojourn in Paris was between 1969 and 1974, and my accounts of watching Alphaville on grass and Band of Outsiders on acid on the pages he cites were actually in New York in 1965 and in London in 1970, respectively. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 12, 1988). — J.R.

THE UNBEARABLE LIGHTNESS OF BEING

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Philip Kaufman

Written by Kaufman and Jean-Claude Carriere

With Daniel Day-Lewis, Juliette Binoche, Lena Olin, Derek de Lint, Erland Josephson, Pavel Landovsky, Donald Moffat, and Daniel Olbrychski.

Before we are forgotten, we will be turned into kitsch. Kitsch is the stopover between being and oblivion. — Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being

The semibearable heaviness of Philip Kaufman, at least in his last three features — Invasion of the Body Snatchers, The Wanderers, and The Right Stuff — is largely a matter of an only half-disguised didactic impulse, a notion that he’s got something to teach us. For a filmmaker as commercial as Kaufman, this impulse becomes worrying chiefly because we emerge from his movies not knowing anything essential that we didn’t know before we went in. We’ve submitted ourselves to a certain intelligence, grandiosity, and slickness, and we may well have been entertained — Kaufman has undeniable craft as a storyteller — but it’s questionable whether we’re any wiser.

There’s nothing at all disgraceful about this. But the suggestion that we’re supposed to be getting something more than intelligent entertainment from a Kaufman film — which seems to hover over every frame like an admonition, almost a threat — leaves an unsatisfying aftertaste. Read more

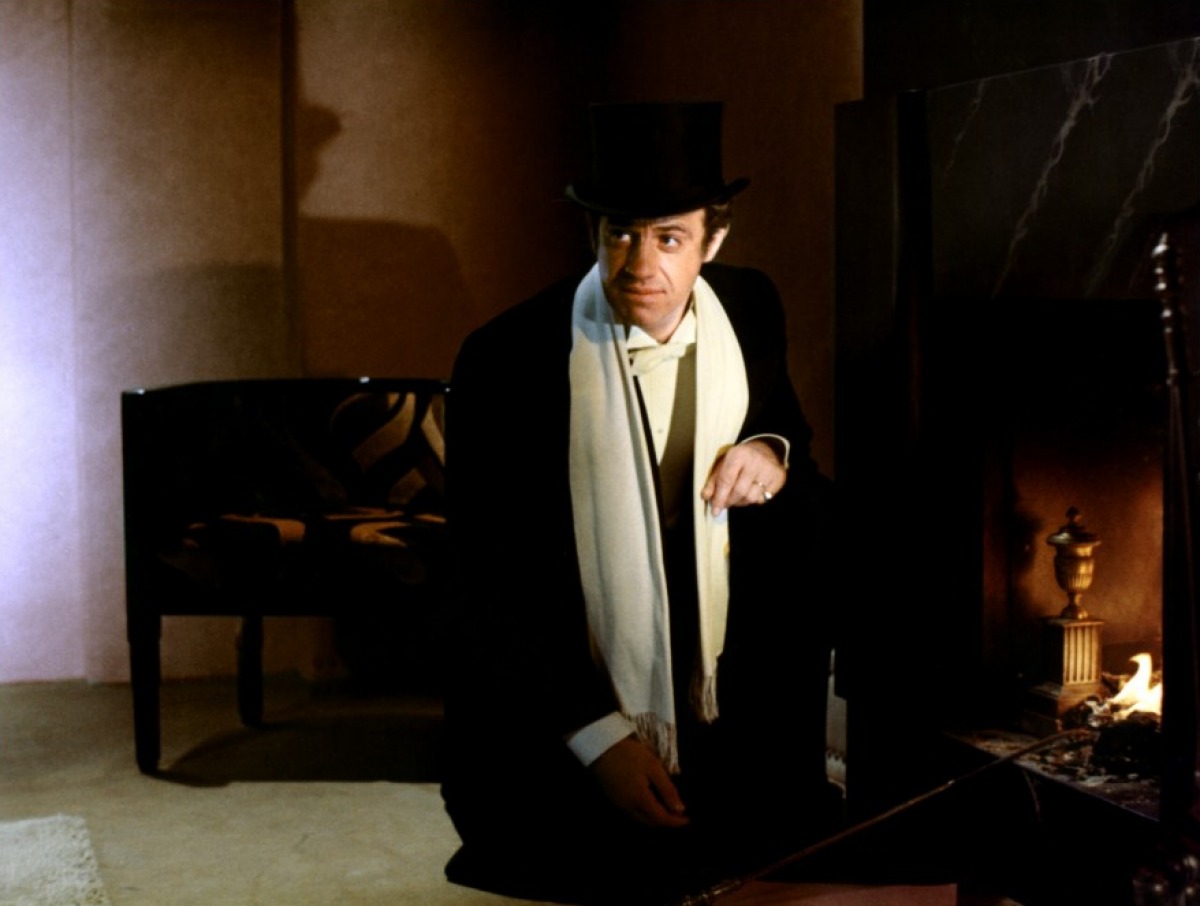

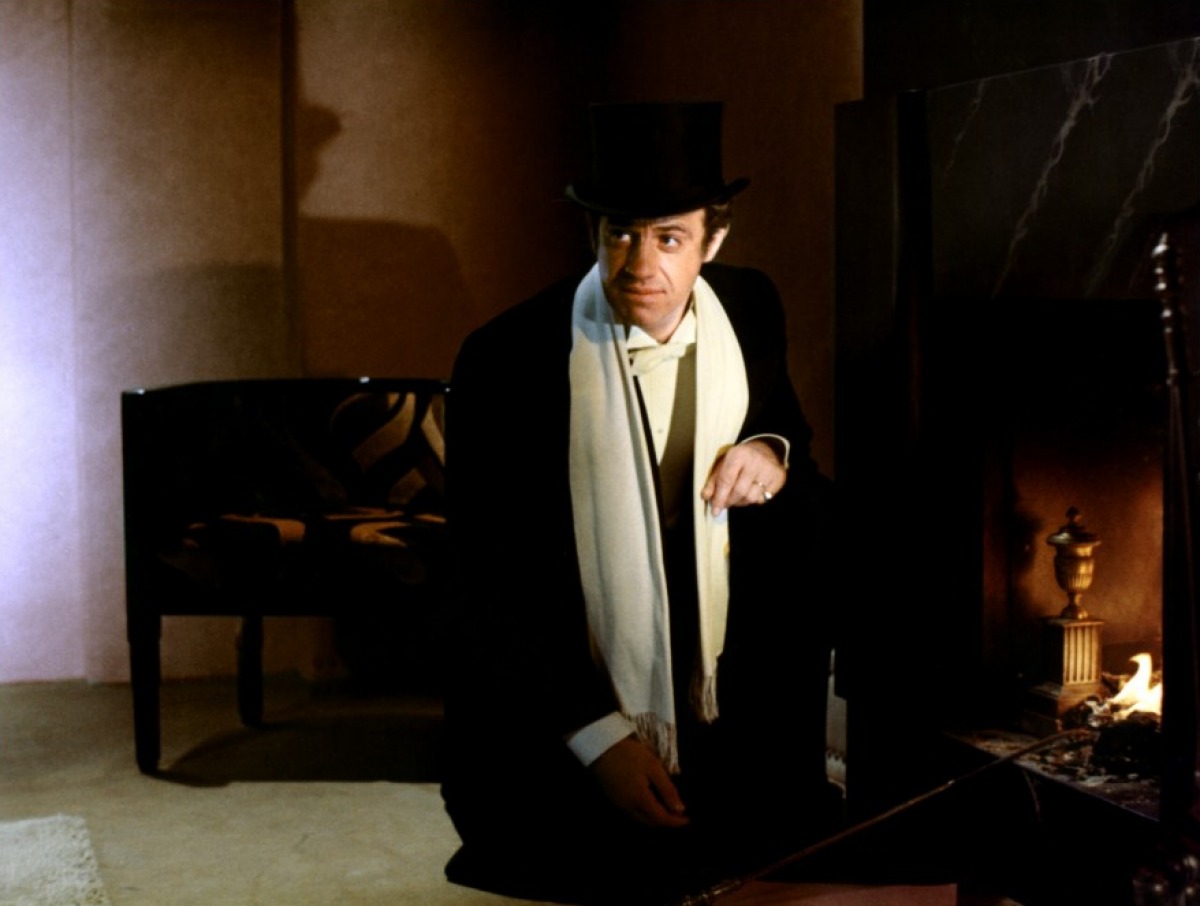

From Sight and Sound (Winter 1973/4). For a subsequent production story about this film written for Film Comment, devoted mainly to a day of studio shooting, go here. –- J.R.

Since the beginning of October, Alain Resnais has been shooting Stavisky, his first feature since Je t’aime, je t’aime (1968). ‘When Jorge Semprurn first spoke to me about making a film on Stavisky,’ Resnais said recently, ‘I admitted to him that at the age of twelve, in the Musée Grévin, I stood dreaming before the wax figure of this character, whom I compared to an Arsène Lupin swindling the rich and helping the poor.’

Actually, Serge Alexandre Stavisky (born in Russia as Sacha) was a swindler who sold 40 million francs’ worth of valueless bonds to French workers, but he moved about in high circles. In spite of a shady past, he was generally known in the early 1930s as a respectable financier with first-rate political connections, associated with the municipal pawnshop of Bayonne. When his fraud was discovered in December 1933, he promptly fled, and the police caught up with him in Chamonix the following month. According to official history, he either committed suicide or was murdered by the police, although the latter explanation appears the likelier one: the Paris press rather implausibly reported that he fired two bullets into his head. Read more