From the Chicago Reader (February 1, 1989). — J.R.

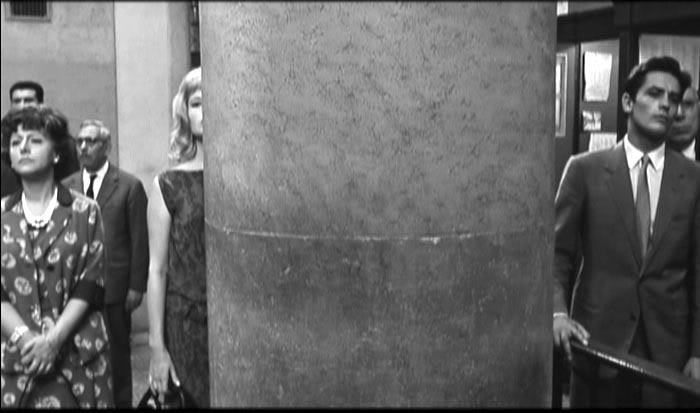

The conclusion of Michelangelo Antonioni’s loose trilogy (preceded by L’Avventura and La Notte), this 1961 film is conceivably the best in Antonioni’s career, but significantly it has the least consequential plot. A sometime translator (Monica Vitti) recovering from an unhappy love affair briefly links up with a stockbroker (Alain Delon) in Rome, though the stunning final montage sequence — perhaps the most powerful thing Antonioni has ever done — does without these characters entirely. Alternately an essay and a prose poem about the contemporary world in which the love story figures as one of many motifs, this is remarkable both for its visual/atmospheric richness and its polyphonic and polyrhythmic mise en scene (Antonioni’s handling of crowds at the Roman stock exchange is never less than amazing). In Italian with subtitles. 123 min. (JR)