These are expanded Chicago Reader capsules written for a 2003 collection edited by Steven Jay Schneider. I contributed 72 of these in all; here are the first dozen, in alphabetical order. — J.R.

Actress

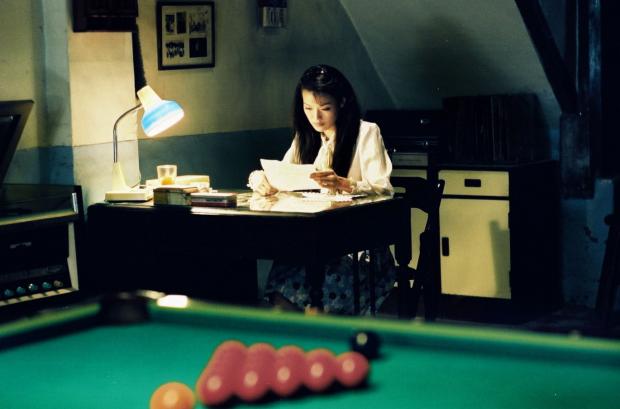

Stanley Kwan’s 1991 masterpiece (also known as Ruan Ling-yu and Center Stage) is still possibly the greatest Hong Kong film I’ve seen; perhaps only some of the masterpieces of Wong Kar-wai, such as Days of Being Wild and In the Mood for Love (both of these also significantly period films) are comparable in depth and intensity. The story of silent film actress Ruan Ling-yu (1910-’35), known as the Garbo of Chinese cinema, it combines documentary with period re-creation, biopic glamour with profound curiosity, and ravishing historical clips with color simulations of the same sequences being shot — all to explore a past that seems more complex, sexy, and mysterious than the present. Maggie Cheung won a well-deserved best actress prize at Berlin for her classy performance in the title role, despite the fact that her difference from Ryan Ling-yu as an actress is probably more important than any similarities. In fact, she was basically known as a comic actress in relatively lightweight Hong Kong entertainments prior to this film, and Actress proved to be a turning point in her career towards more dramatic and often meatier parts. Read more