Here are three of the 40-odd short pieces I wrote for Chris Fujiwara’s excellent, 800-page volume Defining Moments in Movies (London: Cassell, 2007), each of which describes an extraordinary scene from an Alain Resnais film involving camera movement. (There’s also a pretty amazing crane shot in Wild Grass, by the way.) — J.R.

***

1961 / Last Year at Marienbad – The camera rushes repeatedly through the doors of Delphine Seyrig’s bedroom and into her arms.

France/Italy. Director: Alain Resnais. Cast: Delphine Seyrig, Giorgio Albertazzi. Original title:L’année dernière à Marienbad.

Why It’s Key: A climax of erotic reverie in a film of erotic reveries.

Alain Resnais’ most radical departure from Alain Robbe-Grillet’s published screenplay for Last Year at Marienbad is his elimination of what Robbe-Grillet calls a “rather swift and brutal rape scene”. In this ravishing puzzle film about an unnamed man (Giorgio Albertazzi) in a swank, old-style hotel trying to persuade another guest (Delphine Seyrig), also unnamed, that they met and had sex there the previous year, illustrated throughout by subjective imaginings that might be either his or hers, Resnais includes only the beginning of such a scene when the man enters the woman’s bedroom and she moves back in fear. Read more

This was written in 1982 for The Movie: An Illustrated History of the Movies in the U.K., about a movie released the same year. — J.R.

“Little Orphan Annie,” a right-wing comic strip drawn by Harold Grey, was premiered in the New York Daily News in 1924, eventually reaching millions of people through syndication in over five hundred newspapers. In a 1937 survey this feature with its little red-headed heroine was declared the most popukar comic strip in America.

Given the parallels between the economic climate of the Eighties and the period represented in the strip, there is a temptation to translate the main political message of the film Annie as meaning, “Let ’em eat cake” — the essential thrust, after all, of many a Thirties Depression musical, when opulent splendor was largely what the impecunious audience was paying to see (in the Broadway show, this aspect of Annie was reportedly even broader).

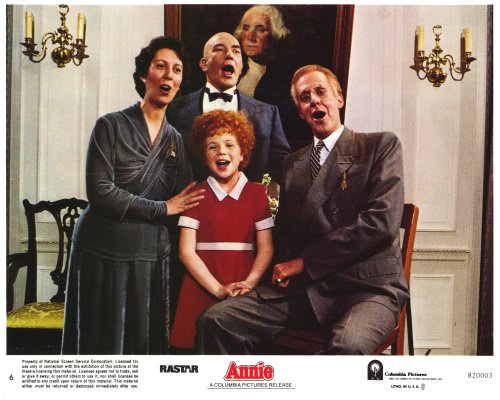

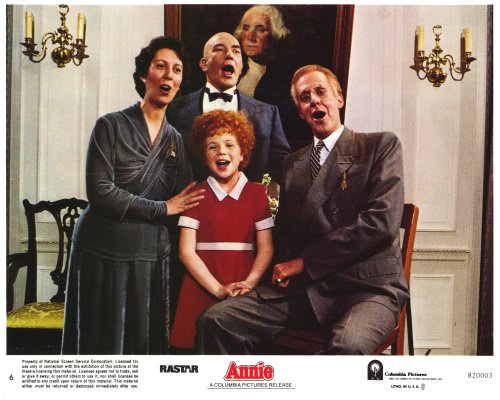

An attempt to liberalize the original strip to fit in with the Eighties seems to be behind a central sequence in the film in which Daddy Warbucks (Albert Finney) takes Annie (Aileen Quinn) and his personal secretary Grace (Ann Reinking) to Washington DC to meet Franklin D. Roosevelt (Edward Herman) and his wife Eleanor (Lois de Banzie); they try (with the help of Annie singing “Tomorrow”) to persuade Warbucks to run one of the “New Deal” youth employment programs. Read more

From the December 4, 2004 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Million Dollar Baby

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Clint Eastwood

Written by Paul Haggis

With Eastwood, Morgan Freeman, Hilary Swank, Jay Baruchel, and Mike Colter

The Aviator

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Martin Scorsese

Written by John Logan

With Leonardo DiCaprio, Cate Blanchett, Alec Baldwin, Alan Alda, John C. Reilly, Kate Beckinsale, Adam Scott, and Ian Holm

Despite his grace and precision as a director, Clint Eastwood, like Martin Scorsese, is at the mercy of his scripts. But in Million Dollar Baby he’s got a terrific one, adapted by Paul Haggis from Rope Burns: Stories From the Corner.

This book was the first published work by Jerry Boyd, writing under the pseudonym F.X. Toole, after 40 years of rejection slips. Boyd had been a fight manager and “cut man,” the guy who stops boxers from bleeding so they can stay in the ring, and he was 70 when the book came out; he died two years later, just before completing his first novel. This movie is permeated by those 40 years of rejection, and the wisdom of age is evident in it as well. Henry Bumstead, the brilliant production designer who helped create the minimalist canvas — he was art director on Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) and has been working for Eastwood since 1992 — will turn 90 in March, and Eastwood himself will be 75 a couple months later. Read more