Here are three of the 40-odd short pieces I wrote for Chris Fujiwara’s excellent, 800-page volume Defining Moments in Movies (London: Cassell, 2007), each of which describes an extraordinary scene from an Alain Resnais film involving camera movement. (There’s also a pretty amazing crane shot in Wild Grass, by the way.) — J.R.

***

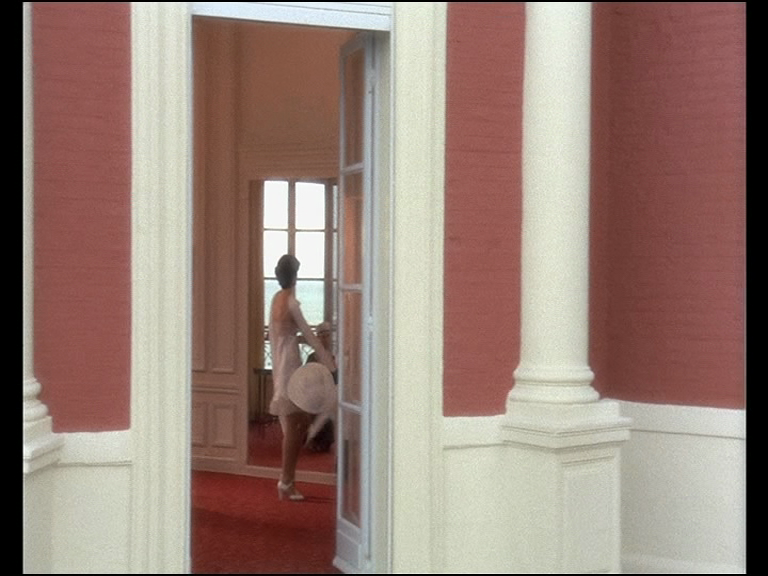

1961 / Last Year at Marienbad – The camera rushes repeatedly through the doors of Delphine Seyrig’s bedroom and into her arms.

France/Italy. Director: Alain Resnais. Cast: Delphine Seyrig, Giorgio Albertazzi. Original title:L’année dernière à Marienbad.

Why It’s Key: A climax of erotic reverie in a film of erotic reveries.

Alain Resnais’ most radical departure from Alain Robbe-Grillet’s published screenplay for Last Year at Marienbad is his elimination of what Robbe-Grillet calls a “rather swift and brutal rape scene”. In this ravishing puzzle film about an unnamed man (Giorgio Albertazzi) in a swank, old-style hotel trying to persuade another guest (Delphine Seyrig), also unnamed, that they met and had sex there the previous year, illustrated throughout by subjective imaginings that might be either his or hers, Resnais includes only the beginning of such a scene when the man enters the woman’s bedroom and she moves back in fear. As in much of the film, Resnais makes the moment campy and melodramatic, as if dimly remembered from an old Hollywood movie. And it occurs 70-odd minutes into a 94-minute film.

While the man’s offscreen commentary insists, “No, no no! That’s wrong – it wasn’t by force…” Resnais retains only one of the scripted shots — “A long, deserted corridor down which the camera advances quite rapidly” in which “the lighting is strange: very weak on the whole, with certain lines and details violently emphasized”. But Resnais places this shot before rather than after the imagined physical contact. This weirdly overexposed, hallucinatory track ends with the camera turning down a separate corridor and then speeding repeatedly, in separate takes, into the welcoming arms of the woman, each time in a slightly different manner. An overheated sexual fantasy in a film chock full of erotic reveries, it marks a voluptuous climax to Resnais’ masterpiece about imagination and longing.

***

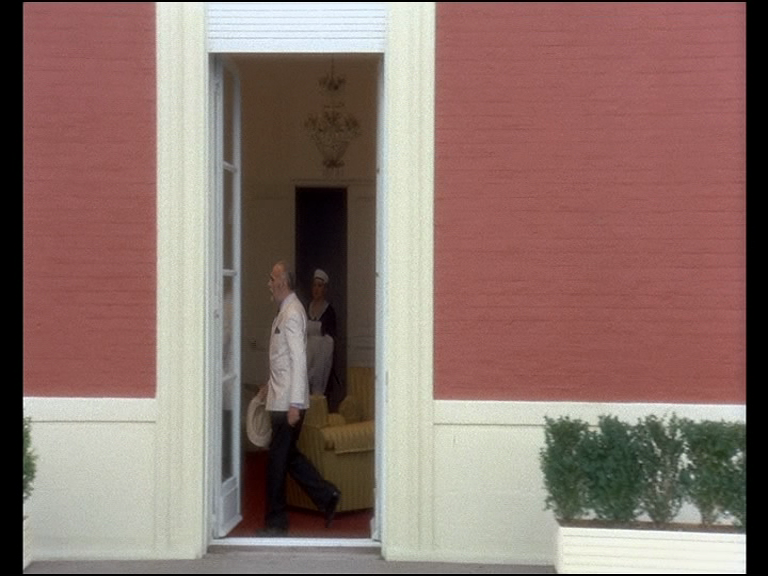

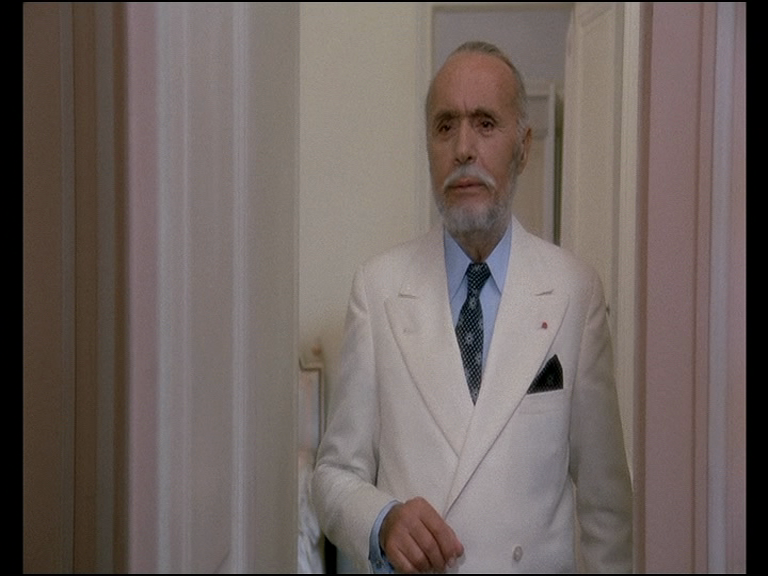

1974 / Stavisky... – When Anny Duperey suddenly turns her head around while Charles Boyer is knocking on the door of her bedroom in Biarritz.

France. Director: Alain Resnais. Cast: Jean-Paul Belmondo,

Charles Boyer, Anny Duperey.

Why It’s Key: An exquisite hommage to Ernst Lubitsch suddenly dovetails into something more perturbing.

It’s part of a flashback early in Alain Resnais’ Stavisky…, when successful con-artist Serge Alexandre Stavisky (Jean-Paul Belmondo) steps into the back of a limo in 1933 Paris with the dapper Baron Raoul (Charles Boyer), asking his friend to tell him about the social “triumph” of Stavisky’s wife Arlette (Anny Duperey), whom the Baron has just seen in Biarritz. While assuring him it was magnificent and describing the lovely weather, we see the Baron approach a palatial resort hotel, walking to the strains of Stephen Sondheim’s first movie score.

This is clearly Resnais’ homage to Ernst Lubitsch, master of 30s glamour and elegance: after we see the Baron enter the hotel and take the elevator, there’s one of Lubitsch’s signature shots —- a crane moving horizontally across the building’s façade, charting the Baron’s progress through French windows in long shot as he crosses Arlette’s sumptuous suite, a flurry of crisscrossing maids marking his path until we see, through the last of the many windows, Arlette getting dressed in her bedroom. A closer, stationary shot shows him knocking at her door, and then —- in one of the most breathtakingly gorgeous, exquisitely-timed cuts in all of cinema —- Arlette in close-up suddenly turns and smiles in response to his knock. It’s a beautiful instant, yet one that carries a creepy foreboding, more Resnais than Lubitsch. And Serge’s concurrent dialogue with the Baron confirms this foreboding: “Nightmare, what nightmare?” —- asking the Baron about the troubling dream he reports that Arlette had.

Scene

***

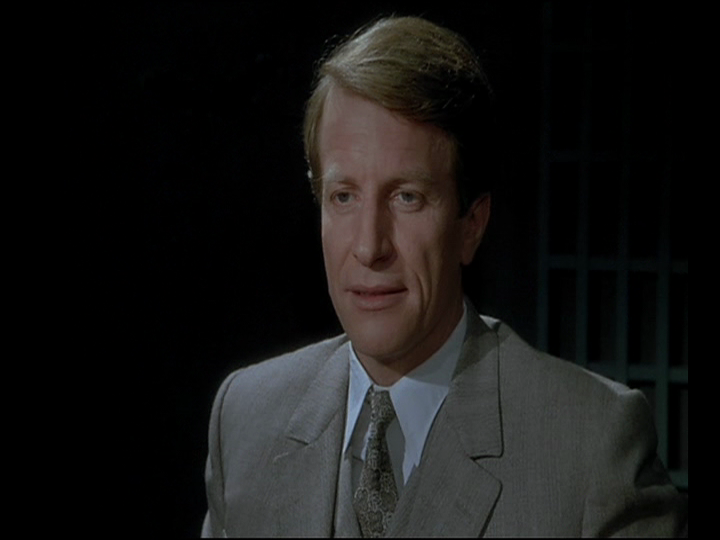

1986 / Mélo – The camera movement circling the three major characters in the first act.

France. Director: Alain Resnais. Cast: Pierre Arditi,

Sabine Azéma, André Dussollier.

Why It’s Key: A flashback and flash-forward are both implicit in one sustained camera movement.

Is Resnais’ adaptation of Henry Bernstein’s 1929 melodrama filmed theater? Yes and no. A personal filmmaker who loves to hide behind his writers, Resnais always has secondary agendas up his sleeve. Here, during the first act of a play about a romantic triangle of classical musicians —- a married couple named Pierre and Romaine (Pierre Arditi and Sabine Azéma) and their friend Marcel (André Dussollier) —- the three are in a patio after dinner, and Marcel, seated across from his host and hostess, is explaining why he gave up hoping for a love of total trust. He recounts playing a Bach sonata in a concert years ago, playing it especially for and to his mistress in the audience, and then discovering her exchanging glances with a stranger in the same audience, something she lied about afterwards.

Resnais films Marcel’s monologue in one take. A slow camera movement that begins behind the couple and ends on a closeup of Marcel subtly traces the adulterous story that will follow from his own viewpoint, through the onscreen groupings of characters: Marcel seen alongside the couple, then between them, then with Romaine, and finally alone. And the same camera movement conveys both of the flow of the Bach he’s playing and him scanning the audience looking for his mistress. In short, Resnais — a master of mixing tenses in his early features like Hiroshima mon amour and Last Year at Marienbad — is showing here how to convey the effects of flash-forwards and flashbacks without leaving the present.