“A movie pours into us. It fills us like milk being poured into a glass.” — John Updike

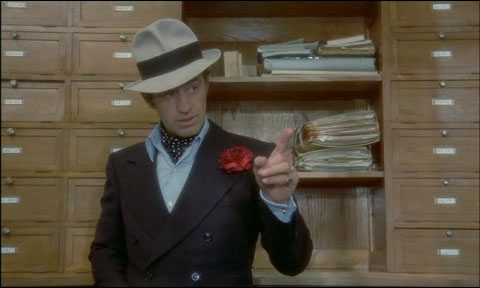

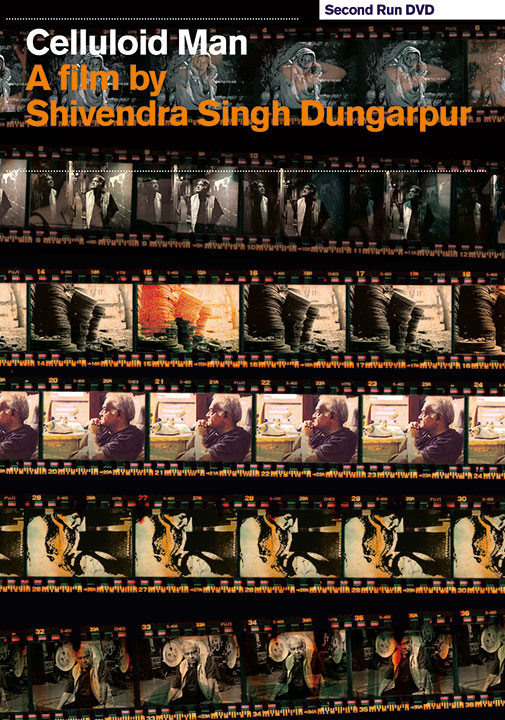

| I must confess that the prospect of viewing a recent two-and-a-half-hour documentary (a recent DVD release of Second Run in the U.K.) about P. K. Nair, the fanatically devoted archivist who helped to found India’s National Film Archive in 1964, didn’t fill me with eager anticipation; the whole thing sounded somewhat esoteric and remote. But in fact, Shivendra Singh Dungarpur’s compulsively watchable and consistently entertaining Celluloid Man (2012) kept me enraptured throughout, not least for its evocations of cinema as a whole and not merely Indian cinema. Early on, when we see Nair addressing us in front of a screen showing Citizen Kane with French subtitles, followed a little later by the opening strains of the film’s soundtrack, it becomes obvious that the critical issues and passions informing Nair’s life are very close to those of his principal mentor, Henri Langlois. And even though the film has a lot to say and show us about the history of Indian cinema, personal and anecdotal (e.g., Ritwik Ghatak’s drinking habits and viewing tastes, Nair’s own history) as well as industrial, it’s the cinema as a whole and why it matters that provides its ultimate framework. |