My column for the Spanish monthly Caiman Cuadernos de Cine, submitted on July 25, 2019. — J.R

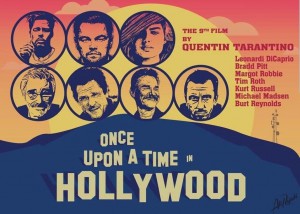

“The strongest argument for the unmaterialistic character of American life,” Mary McCarthy wrote in 1947, “is the fact that we tolerate conditions that are, from a materialistic point of view, intolerable.” Two kinds of doublethink fantasy emanating from this, both deriving from media tropes, can be found in the best and worst examples of recent American cinema that I saw in Chicago in July. These are, respectively, the four seasons of Crazy Ex-Girlfriend (2015-2019), a musical sitcom created by Rachel Bloom and Aline Brosh McKenna, which I saw alone on Netflix via my laptop, and Quintin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, which I saw in 70mm at the Music Box with a full audience shortly afterwards. Significantly, deranged women are the basis of what I find exhilarating in the former and despicable in the latter.

The deranged woman in the first is a high-powered, neurotic Jewish lawyer (Bloom) in New York who rejects her firm’s partnership offer in order to move to a nondescript California suburb “four hours from the beach” to work for a mediocre firm and chase after a former boyfriend, whom she met at a camp as a teenager, meanwhile remaining in denial that her romantic obsession motivated her move. Read more

![220px-Flaming_Creatures_thumb[2]](https://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/220px-Flaming_Creatures_thumb2-216x300.jpg)