From the June 10, 1994 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

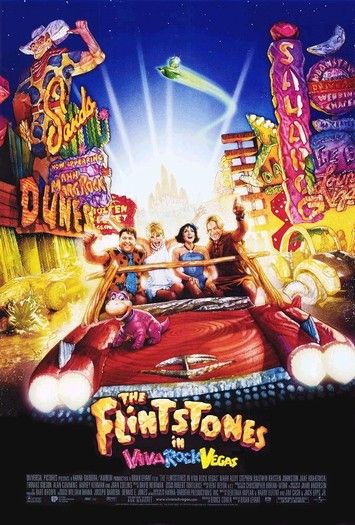

THE FLINTSTONES

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Brian Levant

Written by Tom S. Parker, Jim Jennewein, and Steven E. de Souza

With John Goodman, Rick Moranis, Elizabeth Perkins, Rosie O’Donnell, Kyle MacLachlan, Halle Berry, Richard Moll, and Elizabeth Taylor.

When people come to see an entertainment based on another, earlier entertainment that they have affection for, there are things about it that people want to see. They want to hear Fred yell “Yabba-Dabba-Doo!” They want to hear Wilma and Betty say “Charge It!” They want to hear Dino bark “Yip, Yip, Yip, Yip, Yip” and knock Fred down and lick him silly. And we’ve done those things because we love them, too. — Brian Levant, director of The Flintstones, quoted in the film’s pressbook

It’s quite possible that when someone writes the history of the first hundred years of movies — a period corresponding fairly closely to the 20th century — two decades of that century will be singled out as the most artistically barren: the first and the last. And the principal reasons for that barrenness may turn out to be related: in each decade film, rather than flexing its muscles as an expressive medium, was a relatively inert, inexpressive receptacle for works already fashioned, often in other media. Read more