This profile was published without title in the December 1983 issue of Omni, in a section simply called “The Arts”. -– J.R.

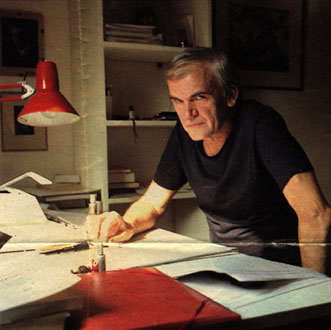

It makes perfect sense that Manuel De Landa, a thirty-year-old Mexican anarchist filmmaker who specializes in the aesthetics of outrage, inhabits a midtown Manhattan apartment so tidy and upstanding that it could almost belong to a divinity student. The point seems to be that if you want to shake the civilized world at its foundations, it helps your credibility if you wear a jacket and tie — especially if you speak with an accent that makes you sound like Father Guido Sarducci. For a talented artist who has an asocial image to sell and a highly social way of putting it across, it isn’t surprising that De Landa makes wild, aggressive films that leap all over the place while standing absolutely still. In The Itch Scratch Itch Cycle (1977) and Incontinence: A Diarrhetic Flow of Mismatches (1978),quarreling couples in tacky settings are subjected to all kinds of optical violence:The camera moves around them in the shape of a figure eight, or De Landa crazily cuts back and forth between two static shots of the principals screaming at each other — as if he were a mad scientist, controlling their shrieks with the twist of a knob. Read more