Published, in a slightly shorter version, in the August 2014 Sight and Sound. — J.R.

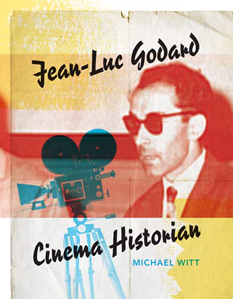

JEAN-LUC GODARD, CINEMA HISTORIAN

By Michael Witt. Indiana University Press, 276pp. £20.65.

paperback, ISBN 9780253007285

Reviewed by Jonathan Rosenbaum

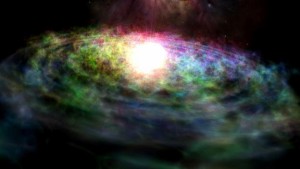

There has been a slew of important books lately devoted to post-60s Godard, including Daniel Morgan’s Late Godard and the Possibilities of Cinema, Jerry White’s Two Bicycles: The Work of Jean-Luc Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville, and Godard’s own Introduction to a True History of Cinema and Television, translated by Timothy Barnard — the latter including Michael Witt’s introductory, 55-page ‘Archaeology of Histoire(s) du cinéma’. But none seems quite as durable, both as a beautiful object and as a user-friendly intellectual guide, as Witt’s superbly lucid, jargon-free book about Histoire(s) du cinéma, Jean-Luc Godard, Cinema Historian.

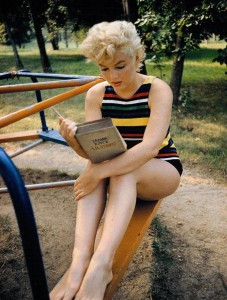

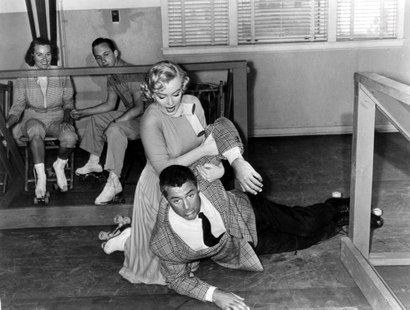

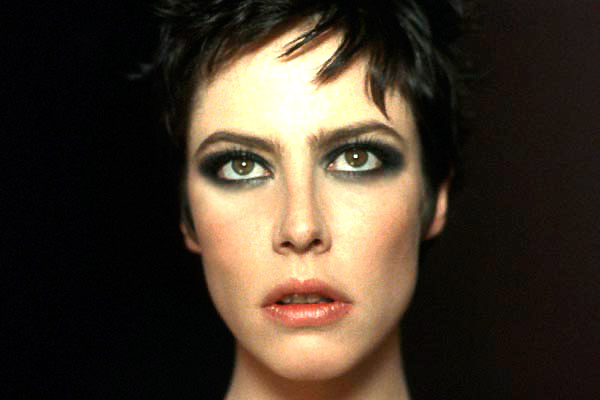

Copiously illustrated with frame enlargements that complement the text without ever seeming redundant, this examination of the philosophical, historical, and aesthetic underpinnings of Godard’s masterwork isn’t only about a four and a half-hour video; it’s also about the work’s separate reconfigurations as a series of books, a set of CDs, and a 35-millimeter feature of 84 minutes (Moments choisis des Histoire(s) du cinéma). Read more