From Cinema Scope No. 34, Summer 2005. — J.R.

As an avid collector of Hollywood musicals, I’ve recently been checking out which items in my collection with optional French dialogue also have French versions of the songs. My father used to teach himself foreign languages by reading translations of some of his favorite English and American novels (e.g., Light in August in German). It’s recently occurred to me that watching favorite Anglo-American movies with foreign subtitles —- something closer to reading a bilingual text —- might also be helpful, though watching a foreign-dubbed version undoubtedly helps even more when it comes to improving one’s speaking knowledge of a particular language. This is one of the many resources afforded by DVDs that most people ignore, myself included. Just as it never occurs to most North American DVD watchers to spend the minimal amounts of time and money needed to acquire a multiregional player and order DVDs from abroad, the linguistic extras available on a good many DVDs slip past most people’s ken because taking advantage of them lies outside their usual habit patterns.

In any case, once I started examining the fine print on the boxes of the musicals in my collection, I discovered that optional French dialogue is fairly common, though whether this includes French versions of the songs is something one can only learn by playing the DVD. For the record, then, The Band Wagon, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, Gigi, and My Fair Lady have all of their songs available in French; Bells Are Ringing, Funny Face, and Silk Stockings have most of their songs in French; but the French-dialogue versions of Guys and Dolls, High Society, Let’s Make Love, Pal Joey, and Singin’ in the Rain revert to English whenever the songs come on. And there’s not always a discernible reason why some songs or musicals get French lyrics and others don’t. Maybe “Bonjour Paris” in Funny Face exists exclusively in English while “Think Pink” gets a French version because the former largely consists of French locations anyway, just as “Drop That Name” in Bells Are Ringing consists exclusively of names. But why do all the songs dealing with correct English pronunciation in My Fair Lady (as well as the others) have French versions? And why does the “Better Than a Dream” duet in Bells Are Ringing get translated while “It’s a Perfect Relationship” doesn’t?

It’s worth adding that Maurice Chevalier sings the French versions of all his songs in Gigi, that the French voices dubbing Marilyn Monroe and Jane Russell in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes are exceptionally well-chosen, and that the translations I can follow in The Band Wagon are often quite precise, as in “Le monde est une scène, La scène est un monde de di-ver-tisse-ment.”

***

I can thank filmmaker Françoise Romand (whose own remarkable 1985 experimental documentary Mix-up should finally be coming out on a multiregional DVD, hopefully by the time this reaches print) for alerting me to one of the two new Chris Marker DVD packages on Arte Video recently released in France, each one an exquisitely well thought-out production in terms of printed as well as audiovisual text. The DVD that Françoise had in mind (“It’s fantastic,” she emailed me. “What a political point of view. Is it too French?”) was Chat perchés (“Perched Cats”), a bracing new political essay by Marker that mainly differs from touchstones like Sans soleil (already available, subtitled, along with La jetée on a separate Arte DVD) by virtue of having pithy intertitles to articulate Marker’s voice in the proceedings rather than an offscreen commentary read by someone else. Indeed, Chat perchés might be called Marker’s latest State of the Body Politic address, shot on both sides of the Atlantic and framed by a fantasy-reverie about graffiti of cartoon Cheshire cats mysteriously appearing in unexpected, hidden places, rather like the proliferating post horns in Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49. No, it isn’t subtitled —- and the accompanying 14-page booklet, « Les chats de la liberté », un conte par François Maspero, with an Afterword by Marker, which I haven’t yet tried to crack, isn’t translated either. But even with my limited French, I found the intertitles pretty easy to follow. And for those who don’t speak a word of the language, the accompanying “Bestiary of Chris Marker” —- five shorts (“Chat écoutant la musique,” “An Owl is an Owl is an Owl,” “Zoo Piece,” “Bullfight in Okinawa,” “SLON Tango”) —- is as wordless as the animals shown, and Marker was even accommodating enough to grant the middle three English titles.

But is it still too French? If so, check out the two-disc set accorded to Marker’s The Last Bolshevik (1993) and Alexander Medvedkin’s 1934 Happiness, both with optional English subtitles (as well as many extras) – even though you’ll have to suffer the Yankee indignity of searching out these treasures via the French titles Letombeau d’Alexandre and Le bonheur. You’ll also have to forego the pleasures of an all-French 30-page booklet edited by Bernard Eisenschitz that’s devoted to Medvedkin and Marker and includes an essay by Jean-André Fieschi entitled (I kid you not) “Chat écoutant la musique”.

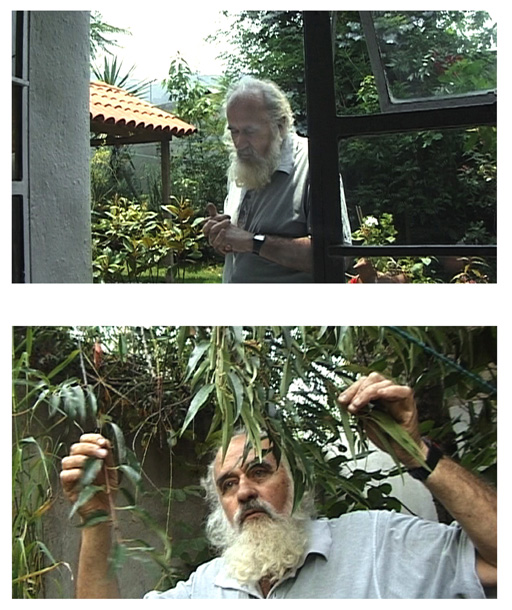

On the subject of subtitled French masterpieces, another special new release is the 4-disc MK2 set of Robert Bresson’s Pickpocket, Procès de Jeanne d’Arc, and L’argent (all excellently transferred), made especially appealing by over three hours of equally subtitled bonuses, including many Bresson interviews and Babette Mangolte’s lovely The Models of “Pickpocket” [see above stills]. Bresson’s films represent a special challenge to DVDs insofar as the relations between sound and image, which are central to their power, are not the same on video as they are on film. This means I’ll have to live with these DVD versions for awhile before I can decide anything conclusive. (I haven’t seen the recently released Artificial Eye transfers of these films on PAL DVDs. New Yorker’s DVD of L’argent, with a transfer almost as good as MK2’s, reached me just as I was finishing this column; it contains the same interviews about that film plus a commentary by Kent Jones that’s sharp if less achieved than his BFI Modern Classic monograph on the film —unlike Yuri Tsivian’s audiovisual essay about Ivan the Terrible for Criterion, which I prefer to his BFI Classic book. Meanwhile, if you’ve been impatient about waiting for Artificial Eye’s announced release of Le diable, probablement in July, and know either French or Italian, you might want to settle on the Italian-subtitled Il diavolo probabilmente… on the San Paolo label.) But it’s already apparent that, in contrast to the virtual evaporation of L’argent on VHS, a significant part of the film’s assault persists on this DVD transfer. And it’s singularly fascinating (if bemusing) to find Bresson in a 1983 TV interview expressing enthusiasm for the latest James Bond feature.

After all these bouquets, I should confess that one drawback to ordering French DVDs from abroad is that when you wind up with a bogus or faulty piece of merchandise, you aren’t apt to find it easy to negotiate a refund or an exchange, so you may just have to resign yourself to your hard luck. The cautionary tales that immediately come to mind are (1) the otherwise watchable Studio Canal/Gallimard Série Noire DVD of Jacques Becker’s Touchez pas au grisbi suddenly and irrevocably jamming about three quarters of the way through, and (2) the surreal experience of inserting an Éditions Montparnasse DVD purporting to be George Cukor’s sublime Sylvia Scarlett into my player and discovering that it contained no film at all but a piece of French rap on audio —- a bizarre manufacturing snafu that I sincerely hope is unique. (Given my unquenchable fascination with Sylvia Scarlett’s subversive 1935 mix of genres and genders, I subsequently came across the rerelease of this title in Montparnasse’s Collection RKO, where I took the plunge again and this time scored successfully.)

***

It’s an essential part of the mythology of corporate capitalism, another kind of “monolingual” persuasion, that most horror stories have happy endings —- an ideology that carries particular force in the realm of restoring eviscerated masterworks. The implicit theory is that the only reason why “the” director’s cuts of Greed and The Magnificent Ambersons (both hypothetical and in fact multiple rather than singular objects) got destroyed were “a few bad apples” in the studios. But check out the hilarious opening sequence of The Corporation (see below) if you want to observe the unpacking of that pernicious, expedient, and compulsive phrase and metaphor, which is also commonly used to “explain” the Abu Ghraib tortures (rather than, say, the policies of Rumsfeld and Bush).

The basic idea is that back in the Dark Ages, we didn’t recognize the bad apples when they fell into our barrels, whereas in the enlightened present we can spot the studio tinkerers immediately. But the exciting as well as vexing two-disc “special edition” of The Big Red One: The Reconstruction released by Warner Brothers demonstrates that the issues of honoring directorial visions are every bit as complex and as ambiguous now as they were then, and that studio ideology continues to play a substantial role in inflecting the complexity involved.

Disc #1 gives us the longer version of Samuel Fuller’s lost masterpiece produced by Richard Schickel, along with optional commentary by Schickel; #2 includes, among other things, a dozen alternate scenes with unremovable commentary by editor Brian McKenzie and post-production supervisor Brian Hamblin, a new documentary on the reconstruction, a Schickel The Men Who Made the Movies documentary about Fuller, a multifaceted Anatomy of a Scene, and, best of all, a 30-minute promo reel from 1980 that contains many missing parts of the 1980 release and helped to inspire the 2004 reconstruction.

The package is intellectually honest enough to allow us to look over the shoulders of the reconstruction team and second-guess or critique some of their decisions — but not so intellectually honest that we’re always allowed a comprehensive view of all the issues involved. (Why, for instance, couldn’t we have had the option of watching and hearing the alternate scenes without commentary?) Significantly, we’re told nothing about the last 15 years of Fuller’s life and career (including his last great film, White Dog, and subsequent films made overseas), and some parts of his earlier work (The Baron of Arizona, Hell and High Water, China Gate, The Crimson Kimono, Underworld U.S.A., Merrill’s Marauders, and Dead Pigeon on Beethoven Street) —- and what’s skimped mainly relates to the parts of his career away from the major studios. Similarly, while the team explains many of its decisions with conventional studio wisdom — “Sam didn’t shoot a lot of coverage,” he kept “crossing the line” in his editing, they didn’t want two scenes in a row involving the shooting of infiltrator-spies, and they felt they had to retain portions of the offscreen narration (all of which Fuller objected to) to tell audiences “where they were” —- I could only wonder what they might have done with the footage of another anarchistic filmmaker like, say, Jean Vigo. Vigo probably didn’t shoot a lot of coverage either; he may have also violated studio editing norms, and may not have always wanted to inform audiences “where they were”. The latter is especially important in Fuller’s case because he’s telling a story in which disorientation —- the soldiers’ and well as our own — is sometimes more important than orientation, commercial considerations be damned. (After all, Fuller’s other most personal and cherished film project was his cozy, self-financed Park Row, and he lost all of the $200,000 he spent on it.) So we have to keep in mind that this is a Warners reconstruction —- at the same time that we readily acknowledge that without the determination and dedication of Schickel and his team, we wouldn’t have this longer version in any form.

***

When an important film gets mutilated, as The Big Red One was in 1980, the potential value of a DVD is to allow us to regain and/or assess part of what was lost. When an important film isn’t mutilated, the potential value of a “special edition” DVD is to allow us to dig deeper into what we like, and this is the encyclopedic aim and achievement of Mongrel Media’s two-disc version of Mark Achbar, Jennifer Abbott, and Jeff Bakan’s first-rate documentary The Corporation, which boasts no less than eight hours of extras. Assessing such a collection is no easy matter, so let’s just say that what we get includes two separate commentary tracks from the three filmmakers as well as “165 unseen interview clips & updates”. The interview clips, on disc #2, can be accessed via two routes — clicking on the still photo of an interviewee (like Noam Chomsky, Milton Friedman, Naomi Klein, or Michael Moore), or clicking on one of the eight topics (like “branding,” “democracy,” “ethics and values,” or “history”) in a subsection awkwardly called “topical paradise”. The main disadvantage with the former is that you have to know or recall what the 40 interviewees look like in order to proceed (it’s too bad that names weren’t also included on the initial menu), and the main disadvantage with the latter is that the eight topics hardly encompass the full range of what The Corporation is dealing with. For the people, I would have preferred the interactive methodology offered by Agnès Varda on her DVD of The Gleaners and I (described in my column in the Summer 2003 Cinema Scope) whereby you can leap immediately from a person in the original film into a supplementary interview clip.

I’ve been seesawing throughout this column between Hollywood and independent sectors, so let me conclude with three more independent items that have just appeared on a couple of new labels. After my excited discovery of Hal Hartley’s new experimental SF feature The Girl from Monday, I was pleased to discover he’s issued his own DVD of half a dozen other experimental films and videos made over the past decade, along with documentation of his theater piece Soon, available from www.possiblefilms.com. And I’m no less happy to report that Travis Wilkerson’s long-awaited ELF label has issued its first two releases, both available from www.scdistribution.com. He Who Hits First, Hits Twice: The Urgent Cinema of Santiago Alvarez is a two-disc set containing eight Alvarez films and Wilkerson’s own Accelerated Under-Development; and John Gianvito’s The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein — his angry, galvanizing epic about the impact of the first gulf war on the U.S., which made 5th place on my Ten Best list for 2001, just below The Circle and ABC Africa —- is also awaiting your belated discovery, especially if you’re wondering whatever happened to American political cinema. By the time you reach the powerful end of his tragic poem, you’ll discover that it’s also experimental, documentary, and narrative, all rolled into one.