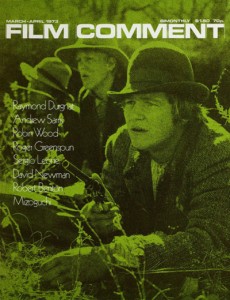

From The Soho News (April 8, 1981). I haven’t reproduced all of this column, preferring to consign most of the latter part of it to oblivion. — J.R.

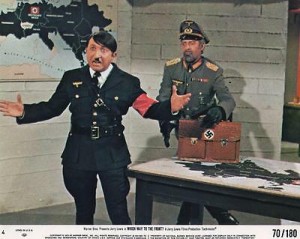

My dream scenario runs roughly like this: J. D. Salinger finally relents and allows Jerry Lewis to direct a film based on The Catcher in the Rye (“Salinger’s sister told me if anyone would get it from him it would be me,” Lewis remarked in a 1977 interview), and civilization as we know it collapses. In the ensuing sociocultural upheaval occasioned by this deconstruction of two critical reputations, anarchy reigns supreme: mad dogs roam the street, The New Yorker shrivels to a cinder out of acute, well-mannered embarrassment; and all those distinguished gray eminences in my profession who fear and loathe Lewis for what he says about their own bodies and social discomforts — some of whom shrink in terror from Tati for the same reasons — run screaming off to the Hamptons and Berkshires to write their own fiction, never to return.

As long as such a personal fulfillment fails to materialize, I guess you might say I’m hardly working. So is the cinema today, at least the kind I care about. Read more