This is the first ten-best round-up I ever did for the Chicago Reader, which ran in their January 8, 1988 issue. Having recently been reading the Library of America’s mammoth collection of Manny Farber’s film criticism (which is coming out in September), I’ve become especially aware of how much one’s taste and preferences tend to change over time. Today, for instance, I suspect I would have placed Mélo in the number #1 slot, and probably wouldn’t include House of Games or Universal Hotel/Universal Citizen in the also-rans but would move them both up to the main list. The first photo, incidentally, directly below, is from Godard’s still woefully neglected King Lear.––J.R.

What is the meaning of a ten best list? For me, at any rate, it means a list of movies with the highest possible mystery quotient — the movies that fascinate me the most because they still have secrets to withhold. And the best litmus test that I know for determining this quality is repeat viewings. If a movie that knocked me out seems less mysterious after a return visit — as was the case with Broadcast News, Cross My Heart, and Orphans — then it doesn’t belong on the list. Conversely, if I haven’t been able to see the film twice, but something about it persuades me that a second look would keep its mysteries alive, then I’m more likely to include it.

While it is customary to fasten one’s ten best list to general comments on what kind of year it was for movies, I can’t in good faith offer such comments without certain caveats, for reasons that are both practical and ideological.

The practical: Having been a regular film critic for only the last 20 weeks of 1987, I can’t claim to have seen all the possible candidates for a ten best list. Before starting at the Reader in August, I was a free-lance film writer and teacher, most recently in southern California; I was also a frequent filmgoer, but as veteran reviewers will tell you, there’s a world of difference between seeing movies often, by choice, as a member of a paying audience and seeing them regularly, most often at press screenings, as a matter of course. Nonprofessional spectators usually restrict themselves to films they have some expectation of liking; professionals, who rarely have this choice, wind up with a more global sense of the spectrum available at any given moment, and their judgments are therefore weighted differently — a broader sense of relativity is established, for better and for worse.

The ideological: If, for the sake of argument, I had managed to see every new film to have played in Chicago in 1987, I still question whether this would have qualified me to make broad generalizations about the state of world cinema last year. Having lived for various periods in Alabama, Vermont, Manhattan, Paris, London, San Diego, San Francisco, and Santa Barbara, I know that the profile of film as a whole looks very different from each of these vantage points; some of these profiles are more fully rounded than others, but none offers a 360-degree view.

It is always expedient to assume otherwise, yet the fact remains that even most “experts” are mainly limited to the titles that the marketplace nudges in their direction, while other worthy films remain in protracted or perpetual limbo. If I were to list all the best features I’ve seen over the past year or so, without any marketplace considerations, I would probably have to include Jean-Luc Godard’s King Lear (which I saw at the Toronto Festival of Festivals, but which hasn’t yet opened anywhere), Mark Daniels’s The Influence of Strangers (an independent New York feature that hasn’t even made it into any festivals that I know of, much less acquired a distributor), and David Sobelman’s Runaways: 24 Hours on the Street (a Canadian TV documentary that hasn’t been exported).

That much said, I have gone ahead and selected ten films that have shown in Chicago in 1987. I have been immeasurably helped in my research by Tom Brueggemann of the M&R theater chain, who has assiduously kept track of all (or nearly all) of the new films to have received theatrical and nontheatrical public screenings here — including Chicago Film Festival selections and one-shot screenings at the Film Center, Facets, and other local venues. And to reiterate my initial point, for “best” one should read “most inexhaustible.”

1. The Horse Thief

Although I’ve been slower to pick up on this than some of my colleagues, there’s no question that part of the big news about recent world cinema is the vitality of Eastern filmmaking, much of which contains a sense of discovery that has all but vanished from the West. It should be pointed out, however, that Tian Zhuangzhuang’s masterpiece from the People’s Republic of China, about a Tibetan Buddhist peasant ostracized from his community, is by no means typical. As English critic Tony Rayns has remarked, it belongs more with “non-Chinese films that have explored the space between the sacred and profane” by Tarkovsky, Herzog, Paradjanov, and Bresson, than with the other innovative “fifth generation” films to have emerged from the Xi’an Film Studio.

Chicago was fortunate enough to have the U.S. premiere of this breathtaking ‘Scope epic as part of an excellent traveling show of foreign films called “The Cutting Edge” (also including Raul Ruiz’s Life Is a Dream and Hou Hsiao-hsien’s The Time to Live and the Time to Die), consisting of movies culled from last year’s Rotterdam Film Festival, which is currently making the rounds at over 15 stateside locations; The Horse Thief opens in New York this month, and one hopes that this will finally enable it to acquire a commercial distributor and gain national press coverage. (For a complex of reasons, it has had only limited distribution in China.) Filmmaking at the highest level, it transcends both its national and regional contexts to convey things about landscape, community, solitude, and death in a poetics of sound and image that is staggeringly beautiful and immediately communicable. Tian has said that he made this film for the 21st century, and the conceit is justifiable.

2. Mammame

Raul Ruiz’s exhilarating dance film, which I also first encountered in Rotterdam last year, has already kept me mesmerized through four screenings without even beginning to grow stale. While his Life Is a Dream (the unfortunate English title for Mémoire des apparences) is a good deal more intellectually ambitious and is a major achievement in its own right, it also has a tendency to ramble, like most of Ruiz’s films. The spirit of play that infuses his enormous body of work, which makes him the most formally inventive of contemporary European filmmakers, also leads to an overall lack of rigor. In this case, however, working with an already existing dance piece by Jean-Claude Gallotta, Ruiz’s Borgesian metaphysics and Wellesian visual rhetoric are firmly kept in line to produce an extraordinary 65 minutes of energizing physicality and shifting spaces.

3. Full Metal Jacket

Stanley Kubrick’s daunting two-part monolith also communicates on a gut level, yet it is the most deceptively simple work he has ever made — and even more resistant to easy interpretation than his 2001: A Space Odyssey. A friend of mine who was a Marine sergeant in the Tet offensive assures me that so many details are botched that the film is worthless as history; insofar as coscreenwriter Michael Herr has recently pointed out that Kubrick set out to make a certain kind of war film before he settled on either Vietnam or Gustav Hasford’s novel The Short-Timers, I see no reason to doubt this testimony. But conventional realism seems so far from Kubrick’s purposes that I can’t dismiss the film for these infidelities either. I’m more inclined to ponder lead actor Matthew Modine’s provocative suggestion that Kubrick’s relationship to other commercial directors is analogous to the position of the early Cubists.

Combining this sense of poetic abstraction with a subject as “hot” as Vietnam (or colonialism in general) is a risky and daring move, but I can’t side with those who fault Kubrick for “coldness” simply because they can’t anticipate or see through him (as they can with a genuine iceberg like Brian De Palma). It’s been at least a quarter of a century since I’ve seen Kubrick’s awkward first feature Fear and Desire (1953) — long since suppressed by Kubrick himself — but it is that touching and compassionate amateur film about young men at war, set in no particular place or time, that Full Metal Jacket evoked for me, refined, perfected, and chiseled to such a fine point that it fully expresses what the earlier film only implied. The vision may be hard as nails, but it is one without villains or other easy bromides.

4. Mélo

Alain Resnais’ passionate history lesson — which adapts a forgotten boulevard melodrama of 1929 without any of the irony or false sophistication that infects most contemporary readings of the past — has an emotional purity and density that makes such French art-house favorites as Jean de Florette and Manon of the Spring look like an amalgam of Tobacco Road and Gidget. It also has four of the finest recent performances in French cinema — by André Dussollier, Sabine Azema, Pierre Arditi, and Fanny Ardant — and reinvents classicism with such freshness, integrity, and feeling that it qualifies as avant-garde in the bargain. Shown at the Chicago Film Festival, this masterpiece has yet to open commercially; if and when it does, it warrants further and deeper discussion.

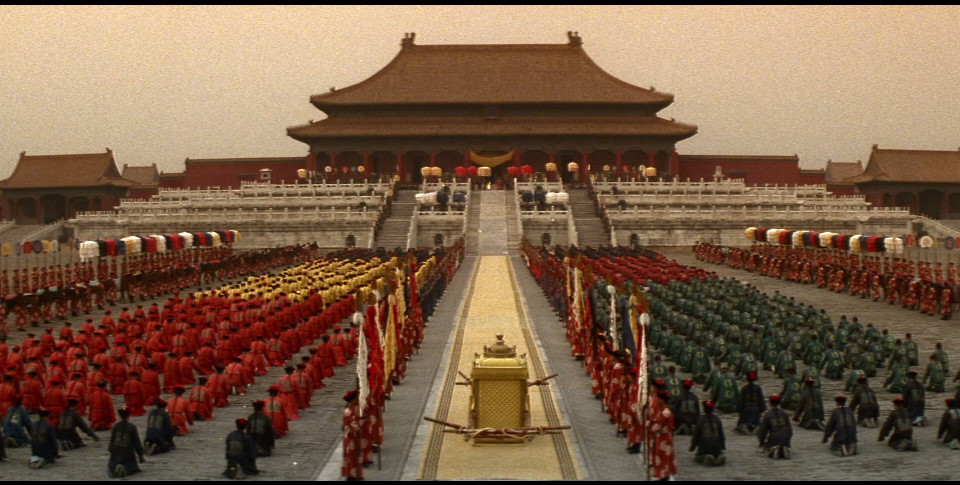

5. The Last Emperor

Another exemplary history lesson, and one that broaches complex questions about 20th-century China with equal amounts of ingenuity and tact, as well as a great deal of visual splendor. Critics who have claimed that Empire of the Sun represents some sort of “coming of age” for Steven Spielberg seem to be confusing aspiration with achievement, but I think the signs of maturity, balance, and objectivity in The Last Emperor, Bernardo Bertolucci’s new feature, are a good deal more demonstrable. The interesting thing about his selective appropriation of Pu Yi’s life (which has significantly met with Chinese approval) is that it doesn’t eliminate the autobiographical self-scrutiny of his earlier films, but subsumes it within a larger and more objectifying framework — the substitution of the state for the family which is central to modern Chinese history.

At first glance, the complex ambitions of this ravishing spectacle evoke Ivan the Terrible in their bold synthesis of historical pageant and psychoanalytical confession, but the crucial difference is that Eisenstein was forging this encounter within his own culture. Bertolucci, by contrast, uses his own outsider’s status as an ingenious route into the alienation of Pu Yi, which becomes in turn the Western spectator’s route into the People’s Republic of China — a process of reeducation for all three at once.

6. Ishtar

I’m willing to concede that Elaine May’s fourth feature is less strong than the three that preceded it. But because I regard May as a major American writer-director and Ishtar as a movie that in no way betrays her uncommon talents, I would have included this title on my list even if it hadn’t sparked off a lynch-mob frenzy in the media. Most of the bile was occasioned by the film’s large budget and its producer and costar Warren Beatty’s handling of the press, both of which are so irrelevant to the film’s merits that they seem beneath discussion. (If waste of money is a “real” issue, why is a much lesser talent like Woody Allen given a free ride and everyone’s blessings for shooting his ludicrous September script twice, with largely separate casts?) A prominent LA publicist told me that she got into trouble with some of her friends simply by laughing at the movie at a press screening.

As I’ve had occasion to argue elsewhere, May strikes me as the closest thing we have to Erich von Stroheim — not merely as an outlaw perfectionist and obsessive truth-teller (“Telling the truth can be dangerous business,” runs the theme song of Ishtar; “honest and popular don’t go hand in hand”) with the darkest view of the American Dream around, but in the very progression of her work. A New Leaf was her Blind Husbands, The Heartbreak Kid her Foolish Wives, Mikey and Nicky her Greed, and now Ishtar is her counterpart to The Merry Widow — a subversion of Hollywood fantasy from within, set in a mythical country. Perhaps the most subversive thing about Ishtar is not so much the failure or mediocrity of her bumpkin heroes (Beatty and Dustin Hoffman, cast against type in Stroheim-like fashion), or the havoc created by their Reaganite ignorance in the third world, with politics and show biz turned into mindless equivalents, as the fact that she loves them just the same. As with Bertolucci, her simultaneous contempt and affection for the monstrous demands to be read, like her ferocious wit, as intricate auto-critique.

7. Landscape Suicide

Significantly, James Benning’s nonnarrative meditation on motiveless murder and landscape is one of the two films here — From the Pole to the Equator, described below, is the other — that I’ve managed to see only once. The relative scarcity of experimental work in relation to the box-office leviathans is of course only one of the reasons they’re less seen and less seeable, but the pleasure and knowledge that these films offer are such that I suspect they would be enhanced by repeated viewings even more than some of the above titles.

The prime advantage of nonnarrative cinema is that it allows one to think, in contradistinction to the conveyor-belt strategies of story telling, which usually permit thoughts to emerge — if at all — only after the films are over. Consequently, although this Benning feature is his first to contain actors — Rhonda Bell and Elian Sacker, who powerfully re-create portions of the court testimonies of Bernadette Protti and Ed Gein, two deranged killers — the principal character is really the spectator’s own mind, confronting these actors and the settings where the crimes took place, and contemplating the relationship between them. The absence of psychologizing, as in Jon Jost’s thematically similar and equally haunting Last Chants for a Slow Dance (1977), liberates the imagination in relation to Benning’s beautifully composed images, and this respect for the viewer’s intelligence pays off in highly charged dividends.

8. Tough Guys Don’t Dance

The biggest surprise of the year was the emergence of Norman Mailer as a bona fide filmmaker. I’m not counting the three vanity productions that he ground out during the 60s; even the best (i.e., most restrained) of these, Beyond the Law, was little more than another recording of his fancies about himself as a movie star, and his exercises in potted film theory in Existential Errands, clearly meant to dignify these excursions, only made them look more tawdry and myopic.

To double the odds against his first “professional” shoot, he decided to adapt the worst and most offensively misogynistic of all his novels. Yet what came out of this constitutes a genuine miracle — over the top and campy, to be sure, yet executed with a good-natured, raunchy gusto and a sense of film style that at once objectifies and satirizes the rampant egomania of the novel. It’s rare that a novelist’s vision ever reaches the screen intact; even a conscientious effort like John Huston’s Wise Blood cools the fever of Flannery O’Connor’s original. Mailer’s trick is to school himself in the best nonliterary stylistic sources (mainly David Lynch), put together a creditable cast, stay behind the camera, and squeeze his best lines out into comic-strip bubbles: the results are excitingly singular and uncompromisingly direct.

9. From the Pole to the Equator

Several years ago, in Manhattan, I had occasion to review a curious film program called “Olfactory Cinema” for the now-defunct Soho News — silent films composed in stop-motion, partially made up of found footage, and accompanied by various scents released from the front row of the auditorium by the filmmakers, Yervant Gianikian and Angela Ricci Lucchi, who had compiled a catalog of over 800 “essences” to go with their films. I wasn’t much impressed by their program. But after a decade of this work and a film about Mahler, this Milan-based couple put together for German TV a stop-frame compendium of documentary footage shot between 1900 and World War I by Luca Comerio, an Italian film pioneer — a film called Dal polo al l’equatore, with a minimalist, nonverbal sound track. I saw this fascinating compilation at Rotterdam last winter (it was shown locally by Chicago Filmmakers), along with The Horse Thief and Mammame, and it has remained embedded in my brain ever since.

The footage concentrates on colonialism and the violence of conquest — recalling the celebrated postcard sequence in Godard’s Les carabiniers, where pictures of the world’s treasures are made to seem equivalent to ownership papers — and ranges from big-game hunting to shots from a moving train to a flock of sheep arranged to spell out “Long live the king” on an Italian hillside. The rephotographed images, edited by the late D.A. Pennebaker, are mesmerizing in themselves, and the sound that accompanies them as well as their order and rhythm make this a disturbing and evocative essay on photography as imperialism — and imperialism as photography — in the first years of this century.

10. Black Widow

Another pleasant surprise of the year was discovering that I could actually like — as opposed to respect and/or squirm through — a Bob Rafelson movie. A very able cast — including Debra Winger, Theresa Russell, Sami Frey, and Dennis Hopper — had something to do with this, as well as a nicely balanced script by Ronald Bass, which I imagine Rafelson also had a hand in. Compared with the macho rich-boy fantasies of Rafelson’s previous work, there is something rather antiauteurist about this well-crafted film noir thriller. But what I find most attractive about it is its capacity to put its sexiness and streamlined story telling to relatively avant-garde purposes: refusing to provide its serial murderer heroine (Russell) with a complete psychology or motive, making her separate marriages and murders a series of existential forays and one-act plays, and developing a doppelganger/transference of guilt theme out of Hitchcock between Russell and Winger that ultimately dissolves the plot into the abstraction of a Persona — without for a moment cheating the spectator who’s simply after a well-turned story.

Considering the number of runner-up favorites that I want to list, in alphabetical order — 28 in all — it must have been an unusually good year for movies: Bad Blood, Bell Diamond, Best Seller, Born in East L.A., Broadcast News (I sincerely hope that Holly Hunter and Albert Brooks both get Oscars), Cross My Heart, The Dead, Dirty Dancing, Homecoming, Hope and Glory, House of Games, Innerspace, The Jester, Life Is a Dream, Matewan, Near Dark, Orphans, The Princess Bride, Rita, Sue & Bob Too, Sammy and Rosie Get Laid, Sign o’ the Times, The Stepfather, Steve Lacy: Raise the Bandstand, Tampopo, The Time to Live and the Time to Die, Universal Hotel/Universal Citizen, Walker, and The Wannsee Conference.

Diane Keaton’s Heaven might be deemed a failure as a whole, but it deserved a lot better treatment than it got for its originality and boldness; much the same could be said of Made in Heaven, at least before its plot became incoherent. Spaceballs and Amazon Women on the Moon were unwieldy messes, but they both had their moments of brilliance: the characters watching the videocassette of Spaceballs in the midst of Spaceballs, as well as some of Mel Brooks’s ethnic humor and the flaunting of his nontechnique (qualities that seem to go together, as they do in Richard Marin’s Born in East L.A.); Joe Dante’s depiction of a failed life reviewed by film critics and demeaned at a celebrity roast in Amazon Women.

The Glass Menagerie sprang to life when the Gentleman Caller arrived, but before that spent too much time with Oscar-mongering and mucking up the theatricality of the original. Raising Arizona had its moments as a brassy piece of junk sculpture, but on the whole seemed much too pleased with itself about them. The River’s Edge, despite its strong subject, was confused and conspicuously overtouted, particularly by reviewers who either missed or forgot Dennis Hopper’s infinitely superior Out of the Blue a few years earlier. And I’m sorry to say that I still haven’t caught up with Robocop.

With apologies, I would like to retire an annual honor that was a longtime feature of this column, the Edgar G. Ulmer Award. As I see it, the original intention of this award was to draw attention to the best example of low-budget exploitation filmmaking released during the year. The problem is, movies of this kind receive so much attention nowadays that the task of making an annual “discovery” in this field seems close to impossible. (By the same token, “bad” movies have probably been receiving more close attention in recent fan publications than “good” movies — a clear sign of Western decadence.) As a replacement to this venerable tradition, I would like to inaugurate the F.W. Murnau Award, to be given each year to a film that provokes a radical revision in our sense of film history — a film that can be young or old in years, but which by nature must be brand-new in spirit. My choice for 1987 is an easy one: Louis Feuillade’s Les Vampires, a ten-part serial released in France in 1915-16, and shown in its entirety at the Film Center last October.