From the Chicago Reader (November 4, 1994). — J.R.

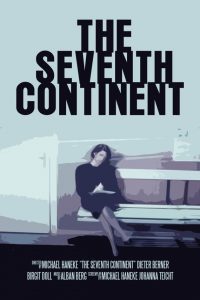

A powerful, provocative, and highly disturbing Austrian film by Michael Haneke that focuses on the collective suicide of a young and seemingly “normal” family (1989). Prompted by Austria’s high suicide rate and various news stories, the film’s agenda is not immediately apparent; it focuses at first on the family’s highly repetitive life-style, taking its time establishing the daily patterns of the characters. The roles of television and money in their lives are crucial to what this film is about, but the absence of any obvious motives for the family’s ultimate despair is part of what gives this film its devastating impact. Its tact and intelligence, and also its reticence and detachment, make it a shocking and potent statement about our times — to my mind a work much superior to the two other films in Haneke’s trilogy about contemporary, affectless violence, Benny’s Video and 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance. With Birgit Doll, Dieter Berner, Leni Tanzer, and Udo Samel. Facets Multimedia Center, 1517 W. Fullerton, Friday and Saturday, November 4 and 5, 7:00 and 9:00; Sunday, November 6, 5:30 and 7:30; and Monday through Thursday, November 7 through 10, 7:00 and 9:00; 281-4114. Read more