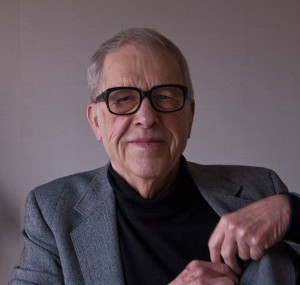

From the Los Angeles Times’ Calendar, June 14, 1987. For readers who might wonder how I could have ever gotten such an assignment, I should point out that in this period, the Los Angeles Times was running anti-Ishtar articles virtually every day over several weeks, so I assume that my contrary position must have had some interest for them strictly as a novelty. This piece is reprinted in my most recent collection, Cinematic Encounters 2: Portraits and Polemics (2019). — J.R.

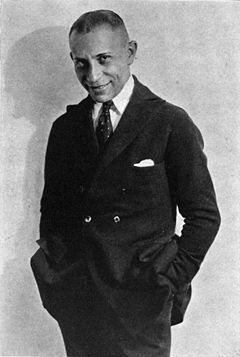

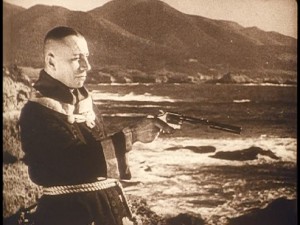

In all of Elaine May’s films, one encounters a will to power, a witty genius for subversion and caricature, and a dark, corrosive vision that recalls the example of Eric von Stroheim. The legendary Austrian-born director who started out, like May, as an aggressive actor (“The Man You Love to Hate”), Stroheim the film maker was known throughoutthe ’20s for his intransigence and extravagance — what one studio head termed his “footage fetish’.

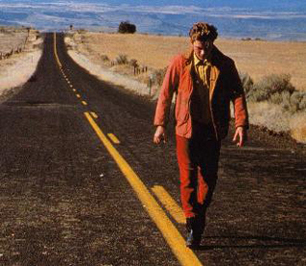

The thematic and stylistic parallels between May and Stroheim are equally striking. Broadly speaking, “A New Leaf” is her “Blind Husbands” — a bold first film about ferocious, cynical flirtation, with the writer-director in the lead part. The Miami of “The Heartbreak Kid matches the Monte Carlo of “Foolish Wives”; the squalor and hysteria of “Mikey and Nicky” hark back to “Greed.” Read more