From Oui (June 1974). –- J.R.

Salome. Meet Carmelo Bene, a vital figure in the Italian avant-garde

whose introduction to American moviegoers is long overdue. Salome,

freely adapted from the Oscar Wilde play, is the latest and perhaps the

most ravishing of his lavish camp spectacles. (Earlier efforts include

Our Lady of the Turcs, Don Giovanni, and One Hamlet Less.)

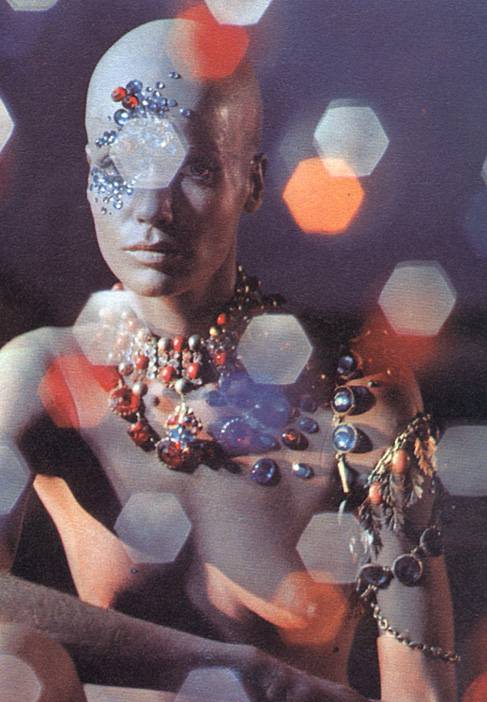

The title role is played by Veruschka –- the high-fashion model who

writhed under the photographer hero at the beginning of Blow-Up

–- appearing bald, nude, and zombielike as she steps out of the water,

decorated from head to foot with multicolored gems. Bene as Herod

upstages everyone with his hysterical nonstop monologues and

Woody Woodpecker laughs. Visually, it’s a riot of extravagant colors

(fluorescent costumes, Day-Glo sets) and opulent debaucheries

flashing by so quickly that everything remains in delirious flux, and

none of the fancy scenic splendors stands still long enough to be

contemplated. Try to imagine Orson Welles’ Macbeth colored in

with a Fellini paintbox, recut by Kenneth Anger, accompanied by

Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony and the Beer-Barrel Polka,

and you’ll get a fraction of a notion of Bene’s giddy madness.

Depravity, thy name is Salome.

–- JONATHAN ROSENBAUM

***

Nada. Claude Chabrol’s current film starts out a little

like The Asphalt Jungle or Rififi. Half a dozen misfits

from different walks of life –- including a young philosophy

teacher (Michel Duchaussoy); a Catalan revolutionary with

a Che Guevara beard (Fabio Testi); an ex-prostitute named

Cash (Mariangela Melato); and a veteran hired gun (Maurice

Garrel) -– join forces and pool their resources to plan a big

caper. But the motives this time are political rather than

mercenary; it’s an anarchist plot to kidnap the American

ambassador in Paris. Adapting a pop thriller by French novelist

Jean-Patrick Manchette, Chabrol turns away from the

examination of provincial and suburban bourgeois behavior

that has concerned him in recent years (in La Femme Infidèle,

Le Boucher, and Just Before Nightfall, among others) to

mount a polemic against gratuitous violence in all its varying

guises. The calculated corruption and sadism of the police are

shown to be equivalent to the recklessness and ruthlessness

of the anarchists, who identify themselves as Nada – the

Spanish word for “nothing”. (Even the American ambassador

comes across as something less than dignified when he is

kidnapped in a fancy bordello, about to sample the pleasures

of a poule dressed up as Salome.) As police and anarchists

pursue their intricate counterstrategies and battle things out

to the bitter end, Chabrol puts a wry pox on both their houses

in this grim adventure of contemporary French terrorism.

-– J.R.