Commissioned by Iranian Film Magazine in early December, 2017. — J.R.

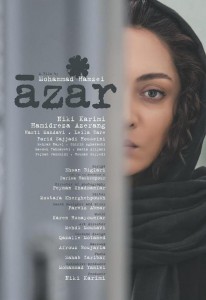

It might be argued that domestic melodramas are often based on contrivances. This is true of both Asghar Farhadi’s The Salesman (2016) and Mohammed Hamzei and Ehsan Biglari’s Azar (2017), two of the better Iranian domestic melodramas that I’ve seen in recent years. But the different ways in which these films handle their contrivances is instructive.

Farhadi — whom I tend to regard as the Elia Kazan of Iranian cinema, for better and for worse, typically generating more heat than light in his most popular works, as Kazan did in On the Waterfront and East of Eden — is more conventionally skillful with his Big Scenes than the team of Biglari (writer) and Hamzei (director) are with theirs. This is because Farhadi knows how to disguise his contrivances so that they don’t seem contrived at all, but dramatically inevitable, such as the sexual impropriety that spurs most of the action in The Salesman as well as the various dramatic confrontations that result from this.

By contrast, the Big Scenes in Azar tend to be awkwardly unconvincing (notably, the accidental death of Saber from a brief scuffle with his cousin Amir arising from a financial dispute), or played down (the uncle of Amir smashing windows in his nephew’s pizzeria with his fist), or else omitted entirely (the pivotal meeting between Amir and his uncle in prison). This is likely because the aim is to provoke thought more than produce strong emotional effects, making it possible to recognize the film’s contrivances yet still appreciate the commentary about Iranian society that they make possible. And the charismatic and persuasive performances by the actors help to make this possible.

Both films are concerned with gender issues, but Azar introduces these issues at the outset by subtly implicating the viewer in their consequences. The very first thing that we see and hear in the film is the revving up of a motorcycle, but it isn’t until a few shots later that we discover that the racer we’ve been watching on a motorcross track is a woman—the film’s title heroine, in fact (Niki Karimi). This only happens when her loving and approving husband Amir (Hamidreza Azarang) says to their little girl Baran, “There she is!”

Indeed, this is a film in which male responses to Azar are both telling and crucial. The fact that she drives a motorcycle is only part of what makes her unorthodox: she also helps to run the pizzeria she has recently set up with her husband, and when their delivery person fails to show up, she gets back on her motorcycle to make the deliveries herself. The first customer is both surprised and favorably impressed, but the second customer manages to confuse her with the prostitute he’s ordered on the phone (another telling contrivance in the script), and it’s the second customer’s error that anticipates the film’s tragic outcome, when she’s obliged to pretend to have been an adulterer and end her happy 14-year marriage in order to placate Amir’s intolerant uncle and get her husband out of prison.

It’s important to realize that Amir is as unconventional in his attitudes as his wife — and the film’s tragedy, epitomized in the blackout of their pizzeria in the final shot, is also his. But the filmmakers are still clever enough to depict them as something more complex than simple nonconformist role models. We learn early on that Azar is a secret smoker, which Saber knows about but not Amir — making the possibility of adulterous impulses plausible to Saber’s father. In short, the visible contrivances of Azar are offset by three-dimensional characters.