Published online on October 12, 2017 by the British Council. — J.R.

Stillness and Life: Abbas Kiarostami’s 24 Frames

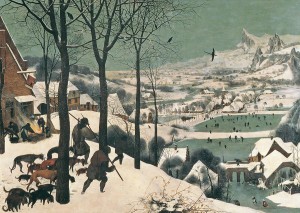

24 Frames (2017), the last film by Abbas Kiarostami, is a feature length experimental work comprising twenty-four vignettes, each four-and-half minutes long and shot mostly in black and white. The majority of these vignettes take place in natural surroundings. In fact, the first shot, of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s painting The Hunters in the Snow (1565), establishes the template for most of the following scenes, which portray different kinds of animals and birds moving around in snowy landscapes. Elsewhere in the film, hunters are kept offscreen but we hear their gunshots. In one instance, they kill a bird and in another, a peaceful fawn. Other segments of the film focus on interior spaces, represented by large, dark windows that reveal only a limited view of the natural world beyond them (birds, or trees, or their shadows). With the exception of the homage to Bruegel, all of the segments are based on Kiarostami’s own photographs.

In 2015, Kiarostami confirmed that he was working on the project, which he began after completing his previous feature, Like Someone in Love (2012). His death in July 2016 meant the film remained unfinished. The final stages of its post-production were completed by his son, Ahmad Kiarostami, who prepared the film for its premiere at the Cannes Film Festival in spring 2017. [1]

The idea for the film is encapsulated in a quotation of Kiarostami’s, which appears as text at the beginning of the film:

I always wonder to what extent the artist aims to depict the reality of a scene. Painters capture only one frame of reality and nothing before or after it. For 24 Frames I started with a famous painting but then switched to photos I had taken through the years. I included about four and half minutes of what I imagined might have taken place before or after each image that I had captured. [2]

With 24 Frames Kiarostami experiments with different tools to fabricate a deceptive sense of reality, a process that started with the inclusion of the video footage in the final scene of Taste of Cherry (1997) and continued through the use of a digital camera to shoot ABC Africa (2001), Ten (2002) and his subsequent films. With his short Take Me Home (2016) Kiarostami began constructing a digital reality through animation and compositing (using green screen to combine different images into one) to further explore the concept of the illusive deception of realism. But in his final film, not only does he manipulate the images, he also blurs the borders between photography (frozen time) and cinema (real time), generating a sense of dialogue between his photographic and cinematic work. In this sense, Kiarostami becomes more self-referential. [3]

In one of the vignettes, a still image is shown of a group of tourists viewing the Eiffel Tower, with their backs to the camera. Soon, snow starts to fall and we see some pedestrians walking in the foreground and later a woman crossing the screen singing the jazz standard ‘Autumn Leaves’. The still image, frozen in time (the past) and the footage of the snow and people moving (in real time) make us aware of the two different levels of reality within the frame. It is through this combination that a sense of nostalgia, melancholy and loss is evoked.

The tone and mood of Kiarostami’s film is reminiscent of Forough Farrokhzad’s, poem, ‘Let’s Believe in the Beginning of the Cold Season’:

And this is I

a woman alone

at the threshold of a cold season

at the beginning of understanding

the polluted existence of the earth

and the simple and sad pessimism of the sky

and the incapacity of these concrete hands.

…

Let us believe in the beginning

of the cold season.

This use of contrasts – movement versus stillness (life and death), harmony and togetherness versus isolation and abandonment – that runs through the film is exemplified by the use of window frames to achieve strikingly beautiful compositions in a number of the film’s segments. The first use of a window occurs in the second frame, in which a snow covered landscape is seen through the window of a moving car. As the car stops, the window is rolled down to reveal a heavenly vision: a gorgeous, crystalline, pure white snowy scene with two black horses dancing lovingly to Francisco Canaro’s tango, ‘Poema’. The scene ends with the window being shut once more, making us aware of the invisible driver and his isolation from the world he sees or imagines.In other segments, windows are also used as a formal device, to create a border between the interior and exterior world and to compose what the we see. They also draw our attention to the subjective viewpoint and the presence of the person who is behind the window, looking outside.

One of the most intriguing, poetic parts of the film is the segment that presents a view of treetops and a cloudy sky seen through a dark window. The gentle voice of a female singer ‘rhymes’ with the slow movement of the clouds and the subtle trembling of the leaves in the wind. The half-open window suggests the possibility of seeing and hearing the beauty of an exterior, unreachable world and possibly being transformed by it while being trapped within the limits of a shadowy interior.

And finally, the most rewarding and dreamlike scene in the film: frame twenty-four, which also features a large window and in which we are given to see two different views within two different frames – both in the same shot (a commentary on cinema). A woman is asleep at her desk by a monitor that shows an image of a couple (actors Teresa Wright and Dana Andrews in the last scene of William Wyler’s 1946 film The Best Years of Our Lives). The desk faces a large window that looks out onto a darkened view of some trees moving in the wind. The frozen image of the couple on the monitor gradually begins to move, and the background becomes brighter as the couple start to kiss. The song ‘Love Never Dies’ by Andrew Lloyd Webber (with lyrics by Glenn Slater) is heard on the soundtrack and the announcement ‘The End’ appears on the monitor. This classical Hollywood happy ending also ends 24 Frames, the bleak yet poetic and beautiful last film of Abbas Kirostami with its hopeful message of love mixed with the artist’s unique sense of irony.

Notes:

[1] Kiarostami had apparently filmed more segments, one of which included the use of The Gleaners by Jean-François Millet, although the reason for leaving them out remains unclear.

[2] In an interview with CNN, Ahmad Kiarostami talks about his father’s creative process: ‘ … Then he moved on to do (animations) with the photos he had (taken). In the end, he … had elements coming from different pictures, but he assembled the whole scene. He made more than 40 frames. He didn’t finish all of them; wasn’t happy with some of them … But the selection that you see here are his originals.’ (Source: http://www.cnn.com/style/article/abbas-kiarostami-24-frames/index.html)

[3] Kiarostami’s work here has been compared to that of some other experimental filmmakers, such as James Benning and Jon Jost. However, it comes closer to the video installations of Bill Viola.