Sorry that the links for this no longer work. — J.R.

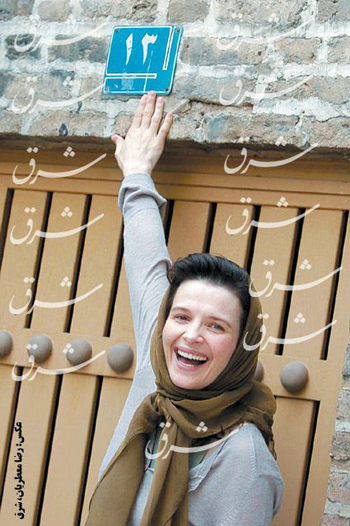

As far as I know, the above photograph of Juliette Binoche in Iran doesn’t come from Shirin, the latest feature by Abbas Kiarostami, which just premiered in Venice. And I’m certain that the two photographs of Binoche below, which I’ve found elsewhere on the Internet, doesn’t come from this film, even though Binoche’s trip to Iran was at Kiarostami’s invitation, and she’s generally credited as the “star” of his new film. For one thing, most accounts seem to agree that Binoche doesn’t wear any makeup in Shirin, and she appears to be doing just that in all three of these photographs.

Judging by some early reviews of Shirin–the best of which is probably Ronnie Scheib’s in Variety, and several of which are usefully grouped together by David Hudson in GreenCine Daily–it’s a development and expansion of “Where is My Romeo?”, Kiarostami’s segment in last year’s Chacun Son Cinéma, in which a wide assortment of females are seen responding to an unseen and possibly imaginary film of Romeo and Juliet. And there’s reason to believe that the unseen film apparently being responded to by Binoche and a good many Iranian actresses in Shirin–apparently an adaptation Farrideh Golbou’s poem “Khosrow e Shirin” by Mohammad Rahmanian, with a very elaborate soundtrack–is imaginary as well.

Many reports and reviews are decrying Kiarostami’s progressive abandonment of his arthouse audience ever since 10, and largely equating this change of direction with a rejection of narrative and storytelling. What they’re usually leaving out is that Kiarostami’s dedication to narrative illusion has remained a near-constant in everything from some of the dialogues in 10 to the final sequence in Five (2003) to “Where is My Romeo?” to Shirin, where not only is the unseen film imaginary, but reportedly the entire film was shot in Kiarostami’s living room with a few chairs, and each actress was asked to gaze at a blank screen. One can trace the same tendency all the way back to the imaginary reverse angles of Kiarostami’s last narrative features, Taste of Cherry and The Wind Will Carry Us, which also might be described as audiovisual variations on the famous Kuleshov experiment. And the theme of deception can be traced all the way back to such earlier films as The Traveler (whose young hero employs a camera without film) and Close-up. So regardless of whether or not Kiarostami is abandoning his arthouse audience, his commitment to fiction and fooling the audience clearly remains intact. [8/31/08]