From the Chicago Reader (April 11, 2003). — J.R.

10

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Abbas Kiarostami

With Mania Akbari, Amin Maher, Roya Arabshahi, Katayoun Taleidzadeh, Mandana Sharbaf, Amene Moradi, and Kamran Adl.

In my mind, there isn’t as much of a distinction between documentary and fiction as there is between a good movie and a bad one. — Abbas Kiarostami in an interview

One way to identify the world’s greatest filmmakers is to determine which ones have found it necessary to reinvent the cinema from the ground up. The names that quickly come to my mind are Antonioni, Bresson, Chaplin, Dreyer, Eisenstein, Godard, Griffith, Kubrick, Mizoguchi, Renoir, Tati, and Welles — a far from exhaustive list of mercurial artists who rethought the nature of the medium not once but repeatedly, most often to their commercial disadvantage.

Not all of these figures qualify as “difficult,” though even such crowd pleasers as Chaplin, Griffith, and Kubrick were called that at some points during their careers. Whether people wound up seeing them as old-fashioned or unfashionable, these artists refused to turn themselves into commodities, alienating even their most passionate fans by confounding expectations and changing the rules of the game, and at times scaring off potential investors. By the time many partisans of Dreyer’s Day of Wrath and Welles’s Citizen Kane finally grasped the reconfigurations of Ordet and Touch of Evil, their directors had switched gears again, delivering the disconcerting Gertrud and Chimes at Midnight.

I’m not alone in placing Abbas Kiarostami in the company of such figures — though he’s been luckier than most of them so far, shooting with such tiny budgets and crews and commanding enough of an international audience that he’s been able to make precisely the films he chooses, even in Iran. (Getting them shown there is another matter.) But I have to confess that sometimes I’ve been slow to recognize and applaud his reinventions of himself and of cinema — just as I’ve sometimes been slow to accept the reinventions of the directors on the above list. We all exhaust certain works and aesthetic positions at different rates, and great artists often exhaust their own before their audiences and critics.

Kiarostami’s 10, opening this week at the Music Box, may well represent one of these disjunctions, for in it he seems to have abandoned much of what he’s done best in terms of visual composition, richness of detail in sound and image, diversity of characters and landscapes, and storytelling. Yet it has forced me to consider whether I’ve been misconstruing what he’s capable of — regarding only the traits I like most as the essential ones. I found 10 more immediately exciting as journalism in some respects than his other recent features. And I found it less immediately exciting as art, though repeated viewings have made it seem artistically fresher every time — even the drama becomes sharper with repetition. Kiarostami’s mastery of his material also remains evident throughout, even if it’s less obvious; the best example is his capacity to make the numerous jump cuts in the opening sequence virtually invisible. As J. Hoberman recently noted in the Village Voice, “Paradoxically, Kiarostami’s own absence serves to push his style to its limit. The more minimal the movie, the more it is recognizably his.” I wonder if this might also be said of his recent half-dozen experimental shorts about water, which are expected to surface at Cannes next month.

Since I regard Kiarostami as the most gifted director now working anywhere in the world, it stands to reason that my expectations when I first saw 10 were abnormally high. It hasn’t met all those expectations, but by changing the rules of the game it has given me more to ponder than recent, more satisfying works by other directors. Kiarostami takes risks that go well beyond the alleged risks taken by commercial wizards such as Steven Spielberg, who’s never come close to truly challenging his audience, not even in 1941.

All of Kiarostami’s fictional and nonfictional features since Where Is the Friend’s House? (1987) have been partly concerned with transactions between poor and rich people, and 10 — which combines fiction and nonfiction in a manner that seems relatively new to him — is no exception. Like his last six full-length films, it makes moving vehicles, especially cars, central — the camera virtually never strays from the front seat of a single car. But 10 is also the first movie since the very atypical early film Report (1977) that’s about the urban middle class, Kiarostami’s own milieu. Perhaps for this reason it’s less multicultural and more specifically Iranian than his others — its world is narrower because its boundaries are more firmly determined by class. (Kiarostami wasn’t born into the middle class — as a youth he worked as a traffic cop, among other things. But the domestic success of some of his movies — Where Is the Friend’s House?, Close-up, and Life and Nothing More — changed all that.) Local Iranian critic Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa points out that his use of the DV camera “has some of the intimacy of home video and some of the surreptitiousness of the surveillance camera” — which can be seen as two primary middle-class emblems.

There’s something indescribably poignant about the pseudonewsreel prologue to The Beginning or the End (1947), a docudrama I recently saw about the development of the atomic bomb, especially now that there’s been talk within our government about using nuclear weapons again. We see actors playing scientists from the U.S., Canada, and the UK burying a time capsule, to be opened in 2446, beside 3,000-year-old California redwoods. “Among the many items and records sealed in the time capsule,” intones the narrator, “were a movie projector, with instructions for its use engraved on copper, and a print of the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer motion picture dramatization The Beginning or the End — a title expressing the fear of people today that a future atomic war may destroy all humanity.”

I don’t know which I find more moving — the faith in 1947 that people will still be around in the 25th century or the worry that they won’t. But the sincere expression of both sentiments makes this moment especially suitable for a time capsule — far more so than any in the movie that follows.

Movies, whether fictions or documentaries, have always captured and preserved moments and fragments of space; rather than being intended for the contemplation of people living in future centuries, they become part of an ongoing dialogue with people around the world about the future of humanity. At once simple and revolutionary, 10 is a modest gesture offered in that spirit — a film that says, “This is where we are now.” It gives us 89 minutes in a car moving through Tehran traffic on ten separate occasions, probably in late 2001 or early 2002. (The sequences are numbered backward like a countdown, from ten to one. Incidentally, the first rocket countdown in history was the invention of Fritz Lang and appeared in his 1928 Woman in the Moon.) With the exception of a single shot taken from just outside the car, everything we see comes from two small digital video cameras attached to the dashboard, framing either the driver or the passenger seated beside her — though sometimes we see the hands of the driver or the passenger in the shots of the other.

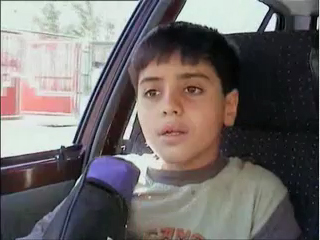

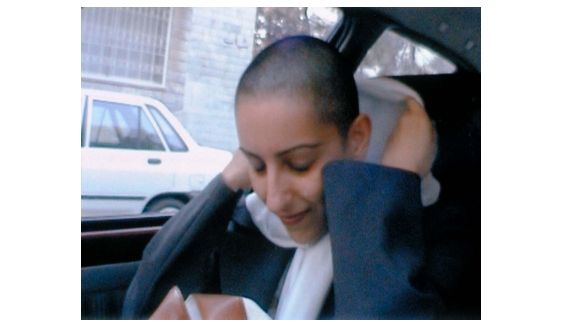

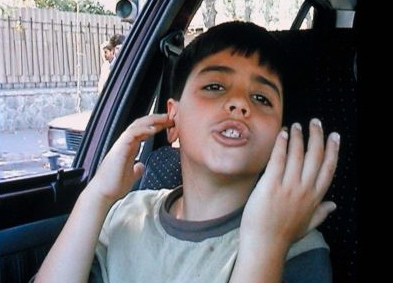

The driver, whom we don’t see until the end of the first and longest sequence, is a beautiful and stylish young woman (Mania Akbari) — a professional photographer who has recently divorced and remarried and is visibly a member of the upper middle class. She gives rides to three people she knows well: her ten-year-old son Amin, her sister, and a woman friend. And she gives rides to three strangers: an old woman and a young one, both en route to or from a shrine, and a prostitute, who gets into the car under the mistaken impression that the driver is a male customer. When the prostitute eventually gets out she finds a real customer; it’s the only time we see her, though it’s from behind, and it’s the only shot in the film that’s outside the car. As critic Gilberto Perez has noted, in a forthcoming piece for the Yale Review, “The film’s sole departure from its two fixed camera positions…implies that if [the prostitute’s] story were to be told a different point of view would be called for.” Amin appears four times — he’s in both the first and final sequences — and the young woman en route to the shrine is given two rides; the remaining four women appear only once each.

It’s worth noting that in recent years Kiarostami has been making films mainly for international audiences, not Iranian ones, which hasn’t been by choice. I heard that The Wind Will Carry Us never opened in Tehran because it was deemed uncommercial, and it seems that ABC Africa hasn’t been seen widely in Iran either. Kiarostami hoped 10 would get a broad Iranian release, but censors said he had to make cuts in two sequences, which would have forced him to remove the sequences entirely — a step that logically would have necessitated retitling the film 8. I haven’t heard which sequences these were, but the likeliest would probably be the one with the prostitute (seven), the one in which Amin discusses the porn his father watches on satellite TV (five), or the one in which the young woman, whose hopes for marriage have recently been dashed, removes her scarf to reveal that she’s shaved off most of her hair (two).

It’s also worth noting that the driver and her son are played by a real mother and son, but the prostitute isn’t played by a real prostitute; according to Kiarostami, he couldn’t find a real one willing to take the part. None of the actors is a professional — apparently the case in all his films, with the exception of Shohreh Agdashlu, who turned pro after playing the female lead in Report, and Mohammad-Ali Keshavarz, who was already a professional when he played the director in Through the Olive Trees (1994).

As in all of Kiarostami’s films at least since the 90s, none of the dialogue is scripted, though how the dialogue is generated has changed. In the earlier features Kiarostami, standing offscreen, would either provoke the actors’ responses or feed them their lines on the spot. For 10 he spent weeks rehearsing the actors, proposing basic situations and asking them to improvise, then left them on their own during the takes, remaining hidden in the back of the car but not directing them. All this careful preparation results in a blend of fiction and documentary so thorough that distinguishing one from the other is impossible while watching the film. Kiarostami has described his method this way: “I state, with a great deal of caution, that direction, in the usual sense of the word, can vanish in this kind of process. In this form of cinema, the director is more like a football coach.” In these terms, all seven actors are powerful team players, and the degree to which Kiarostami has absented himself from their performances is highlighted in the final credits, which consist of only a list of names.

It would be overstating the case to call 10 feminist, yet it broaches the issue of the condition and suffering of women in a world dominated by men in a way no other Kiarostami feature has done. He pointedly limited his male cast to one bratty ten-year-old and brief glimpses of the boy’s father, who’s some distance away in another car as he either drops off or picks up the child. Kiarostami has more to say here about the Iranian patriarchy than ever before, but at no point does the film become preachy. As in his other features, Kiarostami trusts in the intelligence and imagination of the viewer. (Even the two sequences in near-darkness — which recall the passages of darkness in his previous three features — require the viewer’s active participation.)

Amin repeatedly accuses his mother of being selfish, especially because of her work as a photographer and her demands for a divorce. All of Kiarostami’s features since 1988 include either him (Homework, Close-up, Taste of Cherry, and ABC Africa) or a partial or literal stand-in for him (the directors in Life and Nothing More and Through the Olive Trees, the driver in Taste of Cherry, Behzad in The Wind Will Carry Us). The nameless driver in 10 isn’t quite a stand-in, but traces of Kiarostami can be seen in her sunglasses, her photography, and her tendency to lead the conversations with her passengers. His own divorce in the 70s — he’s never remarried — was the major impetus behind Report.

After the local press screening of 10, a colleague and friend who disliked Taste of Cherry so much he hadn’t seen another Kiarostami film until this one, asked me, “If a movie showing the same things were filmed in Chicago, do you think people would find it anything special?” I told him honestly that I didn’t know. After all, there are infinite ways to show “the same things,” and simply agreeing just on what’s being shown in 10 would be no easy matter.

I would argue that 10 is every bit as relevant to Tehran as My Dinner With Andre and Mississippi Burning — two of his favorites — are to New York and Mississippi. And the relevance I have in mind isn’t just the condition of women. There is also, for instance, the blanching quality of the sunlight in Tehran that I recall from my one visit there: some of the sights we see through the car windows may not precisely match the bleached-out reality — even when the camera is facing the sun — but we certainly get a sense of the way the light feels. And we learn a lot about what life in Tehran, a city of more than 12 million, is like through seeing that it’s common to hitch rides and that many people spend as much of their time driving as they would in LA, though Tehran covers less than a fourth of the area.

Of course some people might think that learning what everyday life in Tehran is like is of minimal interest to American moviegoers. But I would suggest that it’s terribly important, especially given the appalling lack of exposure most Americans have to basic information about the people in the Middle East — whose lives our government hopes to alter. We ought to be able to distinguish between the various sects in the region, between the separate languages, between the basic governmental structures. And we ought to know something of who they are as human beings.

Long before September 11, Iranians who came to this country to visit were being subjected to suspicious and hostile treatment. All Iranians crossing U.S. borders, even to change planes, have been routinely fingerprinted and had mug shots taken over the past decade, during which Kiarostami made seven visits to the U.S. — a treatment I didn’t suffer when I visited Iran in 2001. He’d hoped to return last fall, when 10 was showing at the New York film festival, but couldn’t because he was required to wait three months for security clearance. The reason he was given was that the U.S. didn’t have a database for non-Israeli Middle Eastern visitors — which makes one wonder what all the fingerprinting and mug shots were for.

Fortunately it’s easier for Iranian films to get here than Iranians. One might reasonably suppose that the run-up to the war in Iraq has played some part in making 10 more commercially successful in this country than most of Kiarostami’s previous films; it seems a natural human impulse to want to learn something about people our government might choose to bomb in our names. Yet viewers of this movie might be surprised to encounter in the midst of all the Iranian details — saint’s shrines, Islamic divorce laws, chadors — so many Western touchstones: Amin’s T-shirts, his computer programming course, the Hercules video he asks his mother to bring, the flying car he says he saw on a foreign TV channel, his father’s satellite TV and porn, snippets of pop songs, English words (the prostitute laughs as she says, “Sex, love, sex”). I wouldn’t expect anyone to conclude that Iranians are “just like us” — how could they be, when both “us” and “Iranians” are each so culturally, economically, and ethnically diverse? — but one can’t help but notice how many points of reference we share.

My least favorite sequence in 10 is the last, because it adds nothing to what we already know about the driver and her son. My favorite — and that of practically everyone I know who’s seen the film — is the first, which is nothing but revelations. I suspect Kiarostami included the tenth segment mainly for musical reasons, because he wanted a diminuendo after the dramatic crescendo in the previous section — when the young woman reveals her shaved head, laughing as well as crying softly about her situation before falling into an eloquent silence — and thought that the simplest way to achieve it would be to repeat an earlier theme.

Still, in showing the unremarkable — the routine passing of Amin back to his mother from his father — this sequence suggests that routines and rituals have been the main focus of this movie all along. Its concern is errands, meals, memorized prayers, mechanized sex, picking people up and dropping them off, even little comic personal tics, like the way the driver’s sister repeatedly rubs her lip while sitting alone in the car. Nonsubjects, in other words — which have always been an important part of Kiarostami’s films, just as they’re central to our lives.