Commissioned by the University of Chicago Press and written in September 2016; published in November 2017. — J.R.

For all the differences between the history of cinema and the history of the Internet, one disturbing point they have in common is the degree to which our canons in both film and film criticism are determined by historical accidents. Thus we’ve canonized F.W. Murnau’s third American film, City Girl (1930), ever since a copy was belatedly discovered in the 1970s, but not his second, The Four Devils (1928), because no known print of that film survives. Similarly, we canonize Josef von Sternberg’s remarkable The Docks of New York (1928), but not the lost Sternberg films that preceded and followed it, The Dragnet (1928) and The Case of Lena Smith (1929). And it’s no less a matter of luck that all my long reviews for the Chicago Reader, published between 1987 and 2008, are available online, but none of Dave Kehr’s long reviews for the same publication, published between 1974 and 1986—a body of work that, together with Kehr’s columns for Chicago magazine in the 1980s, strikes me as being the most remarkable extended stretch of auteurist criticism in American journalism.

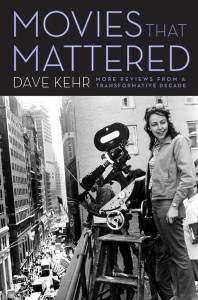

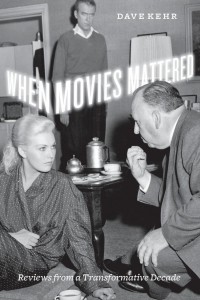

I hasten to add that, unlike the missing films of Murnau and Sternberg, Kehr’s writing for the Reader and Chicago has never been lost. Yet it’s one of the crueler aspects of Internet culture that items that aren’t online are effectively treated as nonexistent—which is what gives this collection and its predecessor, When Movies Mattered (2011), the force of revelation, especially to younger readers encountering Kehr’s pieces for the first time. For the range of films and filmmakers treated, the analytical tools employed, and the intellectual confidence and lucidity of the arguments, Kehr’s prose really has no parallels, which is why so much of it reads as freshly as if it were written yesterday.

The range of films being dealt with is especially impressive: children’s films and Westerns, international art films and American blockbusters, porn and horror, literary adaptations and remakes, comedies and melodramas—all get treated with equal amounts of unpatronizing scrutiny. And because Kehr is also a public intellectual as well as a passionate cinephile, his analyses invariably go beyond issues of style, form, and genre, which are examined with rigorous care, to broader social and cultural matters. The epigrammatic brilliance that often shines in Kehr’s capsule reviews for the Reader is developed into arguments that illuminate entire careers. (“For [Werner] Herzog, plot is mainly a support structure: it holds the images, it doesn’t generate or advance them.”) And sometimes aesthetic points merge seamlessly into social critique: Kramer vs. Kramer’s “chief failing as art — its wavering point of view — becomes its most potent commercial guarantor.” Furthermore, in the course of describing what makes Used Cars “the first post-OPEC comedy, the first film to perceive how treacherously our symbols have turned on us in the past few recessionary, deflationary years,” Kehr carves out an elegant, poetic prose summary of a national zeitgeist:

The affordable family car once represented the fruit of American life: unchecked personal mobility, the unlimited flow of material goods, the triumph of free enterprise—the chrome-plated proof that every American could live like a king. But when those symbols won’t start, when their tanks run dry, they mock us. Rusting in the driveway, they’re like the skull—the memento mori—that Renaissance gentlemen kept on their writing desks: they stare back with intimations of mortality. When the dream car loses its patina, its promise of health, wealth, and happiness, every car becomes a used car—a ton of metal twisting in the sun.

Writing about adaptations of Joseph Conrad, F. Scott Fitzgerald, E.M. Forster, Thomas Hardy, Ernest Hemingway, and William Shakespeare, Kehr demonstrates that he’s also a first-rate literary critic, but not one who ever loses sight of the cinematic, historical, and cultural issues at stake in these adaptations. And despite his decision to subdivide these essays between appreciations of favorites and “autopsies/ minority reports,” these examinations rarely qualify as “thumbs up” or “thumbs down” reviews. His exemplary consideration of Bernardo Bertolucci’s much-reviled Luna—probably the best critical treatment that film has received anywhere, and one that drove me immediately to take a second look—turns out to be every bit as conflicted as the object of its focus, even though it’s grouped with Kehr’s favorites:

The usual line on films as radical as this is that you’ll either love ’em or hate ’em. I found myself loving and hating Luna indiscriminately, and sometimes simultaneously. I hated its hermeticism, its inconsistency, and its lack of discipline, but I loved its size, its audacity, and its complete unpredictability. The film may turn out to be more valuable for its outrages than for its accomplishments: if it doesn’t satisfy, it still gives a damn good shake. Meanwhile, it’s worth bearing in mind that one of the more pertinent derivatives of the Latin luna is “loony.”

In short, even though Kehr remains one of the most responsible of film critics, he also proves that one reason why he deserves this distinction is that he knows the value of irresponsibility—as his treatment of Russ Meyer’s Supervixens also demonstrates.

In order to appreciate fully the historical importance of these essays, one should distinguish between the relative homogeneity of academic and journalistic criticism in Continental Europe and the United Kingdom and the relative estrangement between those realms in the United States—an estrangement that becomes especially pertinent during the 1970s and 1980s, the same period when Kehr was publishing these essays.

In his Introduction to When Movies Mattered, aptly subtitled Reviews from a Transformative Decade, Kehr focuses on the parallel developments of the alternative press and auteurist criticism as sparked by Andrew Sarris’s seminal The American Cinema (1968), inspired in turn by writing about Hollywood that appeared in Cahiers du Cinéma during the 1950s and 1960s, before more theoretical and ideological persuasions overtook that magazine for a spell in the 1970s, in response to the uprisings in May 1968. Although Kehr discusses these developments chiefly in order to clarify his distance from them, it’s important to acknowledge that while Roland Barthes and Umberto Eco were able to air their positions in mainstream newspapers, and Peter Wollen, writing under the pseudonym of Lee Russell in New Left Review in the U.K., was able to combine a certain amount of academic film theory with auteurist journalism, Kehr was operating from a different set of platforms in the pages of the Reader and Chicago, where no such accommodations would have been tolerated. Yet in spite of these distinctions, the differences between Lee Russell’s “structural” analyses of Samuel Fuller, Budd Boetticher, and Anthony Mann and Kehr’s treatments of Boetticher, Clint Eastwood, Stanley Donen, and Elaine May is arguably more a matter of terminology and prose than one of critical and analytical substance. Stated differently, Kehr’s acquaintance with theory, ideology, and critical methodology often arguably runs deeper than his writing is ready to acknowledge, given the orientation of his audience.

***

When the Reader started to post its movie reviews online in March 1996, I had already been their staff critic for nearly a decade, thanks to Kehr having named me as his successor—a gift that afforded me not only the best job in my career but a unique one in terms of space and freedom because of Dave’s own initiatives during his stint at that alternative weekly. The posting of the Reader’s extended film reviews gradually proceeded backwards, from present to past, eventually encompassing all my long reviews but lamentably stopping short of including any of Dave’s. This had the untoward effect of creating an unfortunate cleavage between our online profiles that has persisted ever since, despite the posting of all of Dave’s capsule reviews on the Reader’s web site and all his New York Times writing (including his superb weekly DVD column, which lasted from 1999 through 2013) on their own site, not to mention the excellent film blog open to group discussions (“reports from the lost continent of cinephilia”) that he maintained for many years at davekehr.com—no longer active but still available online the last time I looked.

That Kehr considers cinephilia a “lost” continent and that the titles of his collections are in the past tense are what mainly separate his current position from mine—a position that I’m sure has also been inflected by the urgency of his exciting and vigorous second career as a adjunct curator and archivist at the Film Department of the Museum of Modern Art since late 2013, which is dedicated to resurrecting and preserving treasures that otherwise might be lost. I’m sure his pessimism is well founded (and grounded), even if I can’t entirely share it. I also wonder if the banishment of his best prose from the Internet may have played some role in his viewing of cinephilia as largely a thing of the past. Reading this prose now, and coordinating some of my own viewing in relation to it, it feels very much alive to me.