From the Chicago Reader (January 10, 1997). — J.R.

Compiling a list of the best new (or “new”) movies that opened in Chicago in 1996, I’ve come up with 40 titles, half of which are foreign-language pictures. Many of my colleagues would regard choosing so many foreign movies as perversely esoteric, but it’s hard for me to fathom why. I willingly concede that this country has one of the strongest national cinemas in the world — probably the greatest, which is fully reflected in my including 19 American films in my list and only 5 from France; 3 from Taiwan; 2 apiece from England, Hong Kong, and Iran; and 1 each from mainland China, Denmark, Italy, Poland, Russia, Spain, and Vietnam.

Of course I haven’t seen nearly as many non-American films as American, but I’ve made a stab at seeing those that have made it to Chicago. I have long been bewildered by how the majority of my colleagues almost never mention any cinema that isn’t English-language when they draw up their end-of-the-year lists. Is American cinema really that wonderful and non-American cinema really that awful? Of course not; the reason most reviewers don’t include foreign pictures on their lists is that they don’t see them. Read more

A chapter from my book Film: The Front Line 1983. Apart from integrating a footnote into the main body of the text and eliminating a long out-of-date filmography, I’ve kept this text pretty much as I wrote it.

Adynata exists on both film and DVD, but, discounting unofficial/pirated/ underground sources, seems available, alas, only at institutional prices (from Women Make Movies and Electronic Arts Intermix — the latter of which also distributes X-Tracts and Jennifer, Where Are You?, both on video, along with Thornton’s subsequent works, 21 titles in all). One can, however, access her radically different and recent Novel City (2008), about seven minutes long, which draws on a few of Adynata‘s sounds and images and adds several others, here. — J.R.

X-Tracts (1975) and Adynata (1983) have one very interesting and crucial aspect in common: they are montage films structured around the possibility ofan auto-critique, the activity of reading one’s self. The fact that Thornton performs this work in X-Tracts is what gives the film interest; the fact that we are able to perform this work in relation to Adynata is what gives it an even greater interest and importance. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, September 1975. — J.R.

Brats

U.S.A., 1930

Director : James Parrott

Cert–U. dist–Kingston. p.c/p–Hal Roach. For MGM. story–Leo

McCarey. dial–H. M. Walker. ph–George Stevens. ed–Richard Currier.

l.p–Stan Laurel (Himself/His Son), Oliver Hardy (Himself/His Son).

732 ft. 20 mins. (16 mm.).

While Laurel and Hardy try to play checkers, they are repeatedly interrupted by the fights and antics of their two sons, miniature replicas of themselves; eventually they send them up to bed. After putting on their pyjamas, the kids continue to wreak havoc: as Hardy Jnr. looks under the bed for a mouse, it crawls on to his bottom, and Laurel Jnr. fires at it with a toy gun; Hardy Jnr. howls in pain, and Laurel Jnr. fills the bathtub to offer him relief, leaving both taps on. They spar with boxing gloves before their fathers appear once more, and Hardy is persuaded to sing them a lullaby; when one of the kids asks for a glass of water and Hardy opens the bathroom door, the room is flooded.

A clever use of double sets — each room scaled separately to match the respective sizes of fathers and sons — and a baby Hardy without a moustache aren’t really enough to make this more than a minor Laurel and Hardy effort, although there are a few compensations along the way, most notably Laurel’s adage that “You can lead a horse to water but you can’t make a pencil lead”, and Hardy’s lullaby, which quickly gravitates into a scat-yodeling exercise. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 8, 1991). — J.R.

PRIVILEGE

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Yvonne Rainer

With Alice Spivak, Novella Nelson, Blaire Baron, Rico Elias, Gabriella Farrar, Dan Berkey, and Yvonne Rainer.

Approached as a narrative, Yvonne Rainer’s sixth feature takes forever to get started and an eternity to end. In between its ill-defined borders, the plot itself is repeatedly interrupted, endlessly delayed or protracted, frequently relegated to the back burner and all but forgotten. All the way through, the action proceeds like hiccups.

Yet approached as an essay, Privilege unfolds like a single multifaceted argument, uniformly illuminated by white-hot rage and wit — a cacophony of voices and discourses to be sure, but a purposeful and meaningful cacophony in which all the voices are speaking to us as well as to one another.

Everything in the movie can and should be experienced as part of an ongoing dialogue, and it’s no small tribute to its overall coherence and impact that one wants to have an ongoing dialogue with the movie–talk back to it, argue with it — and that one has to if the movie is going to make any sense at all. The dialogue may deliberately go in and out of sync with the on-screen characters, the characters may be periodically played by different actors, and the shots may shift without notice between color and black and white. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, March 1975 (Vol. 42, No. 494). — J.R.

Gambler, The

U.S.A., 1974

Director: Karel Reisz

The limitations and pretensions of James Toback’s script for The Gambler are so formidable that it is difficult to conceive of any director redeeming or transcending them. A Q.E.D. (indeed, virtually ABC) demonstration of a masochist’s steady progress to self-obliteration, peppered with ‘significant’ flashbacks and literary quotes, it involves gambling no more and no less than The Conversation involves tape recording — which is to say, incidentally rather than substantively. By the end of the first reel or so, it is already painfully clear that Axel Freed (James Caan) is more interested in losing than winning, and from that point onward narrative interest is increasingly diffused by a clinical spelling out of his condition which has all the earmarks of a stacked deck. The problem is not so much a surfeit of psychological analysis — the script offers hints, not explicit causes explaining Axel’s condition — as too little to account for his behavior naturalistically, and too much to permit any sustained acceptance of the character on an allegorical or mythical level. Unlike the abnormal, high-strung and death-defying auto racer played by James Caan in Hawks’ Red Line 7000, there is nothing in Axel that suggests hidden depths; indeed, despite Caan’s consistent professionalism, the actor appears to be as uninterested in his character as Axel seems to be in himself. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (2002). — J.R.

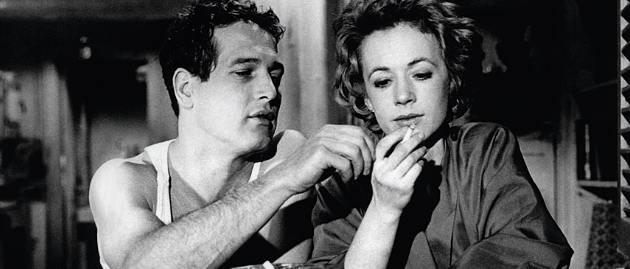

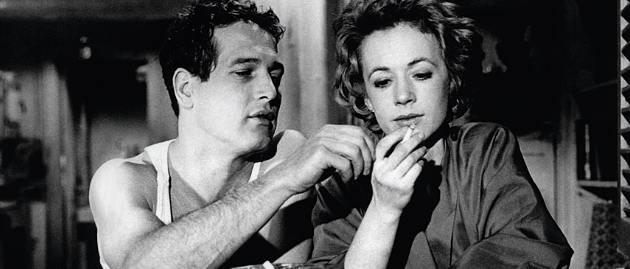

Robert Rossen’s 1961 feature is a somber morality play postulating as existential hero a pool hustler perfecting his craft (Paul Newman at his best). It makes wonderful use of its seedy locations (memorably filmed in black-and-white ‘Scope by Eugen Shuftan, who won an Oscar for his work) and its first-rate secondary cast (Piper Laurie, Jackie Gleason, George C. Scott, Myron McCormick, and Murray Hamilton). Adapted by Rossen and Sidney Carroll from a Walter Tevis novel, this picture is so much better than Martin Scorsese’s belated sequel The Color of Money that they don’t even belong in the same category. A postnoir melodrama with metaphysical trimmings, it does remarkable things with mood and pacing, and the two matches with Gleason as Minnesota Fats are indelible. 135 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From Oui (October 1974). — J.R.

La Gueule Ouverte. A 5O-year-old Frenchwoman named Monique (Monique Melinand) is dying of a painful disease. She gradually loses the ability to communicate with any ease, and finally the power to speak at all. Eventually she’s moved from the hospital to the family’s house in Auvergne, where her husband Roger (Hubert Deschamps), along with her son Philippe (Philippe Leotard) and his wife Nathalie (Nathalie Baye), take care of her and wait for her to die. It’s a painful and less-than-inviting subject for a film, but somehow Maurice Pialat works wonders with it. Too recognizable and embarrassing to be strictly sentimental and too inventive and observant to be predictable. his story moves like a string of terse epiphanies, beautifully recorded by Nestor Almendros’s camera. The characters are neither bigger nor smaller than life: Roger is a drunken grouch whose idea of kicks is to cop a feel from a pretty girl while she changes sweaters in his clothing shop, yet he is the one most affected by Monique’s death. Philippe screws Nathalie and then goes hunting up prostitutes in his desperate flight from the fact of death. Father and son don’t like each other much, and when Philippe and Nathalie drive away at dusk– an extraordinary extended shot that encapsulates a lifetime into a few miles — we can be confident that they won’t be coming back again. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 10, 1992). — J.R.

David Cronenberg’s first masterpiece since Videodrome breaks every rule in the book when it comes to adapting a literary classic — perhaps On Naked Lunch would be a more accurate title — but justifies every transgression with its artistry and sheer audacity. Adapted not only from William S. Burroughs’s free-for novel but also from several other Burroughs works (e.g., Exterminator and the introduction to Queer), it pares away all the social satire and everything that might qualify as celebration of gay sex, yielding a complex and highly subjective portrait of Burroughs himself (expertly played, under his William Lee pseudonym, by Peter Weller) as a tortured sensibility in flight from his own femininity, who proceeds zombielike through an echo chamber of projections (insects, drugs, and typewriters) and disavowals. According to the densely compacted metaphors that compose this dreamlike movie, writing equals drugs equals sex, and William Lee, as politically incorrect as Burroughs himself, repeatedly disavows his involvement in all three activities. Maybe it’s Cronenberg himself who’s doing all the disavowing; like David Lynch, his imagination seems to depend on ideological unawareness, but here, at least, it produces the most ravishing head movie since Eraserhead. Read more

From Sight and Sound, February 2006. — J.R.

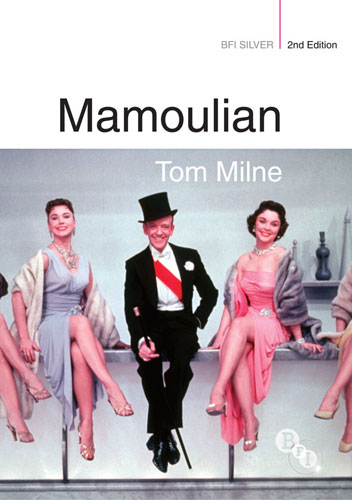

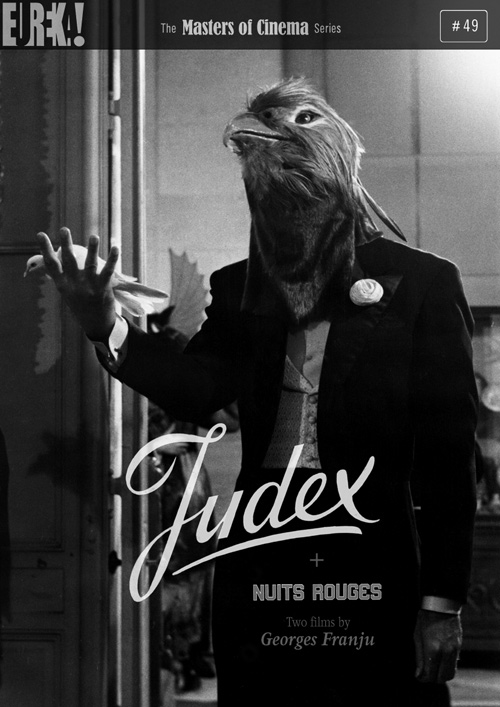

I was a fan of Tom Milne’s writing before I ever met him, having not only read his passionate criticism religiously in Sight and Sound during the 1960s, but also having selected his review of Franju’s Judex for a never-published anthology, Film Masters, that I edited in New York, shortly before I moved to Paris in 1969. I acquired permission to reprint it from Penelope Houston, the magazine’s editor (whose vibrant review of Last Year at Marienbad I was also including), and having published virtually nothing of my own at the time, I was inordinately pleased when Penelope wrote me back that Tom had said, “Whoever he is, tell him he’s got taste,” for that review was one of his own favorites.

I think I must have met him for the first time circa 1974, in London, when I was preparing to live there and start work as assistant editor to Richard Combs on Monthly Film Bulletin, Sight and Sound’s sister magazine at the BFI. As a former assistant to Penelope, Tom was still a key contributor to both magazines; one might even call him — I would indeed call him — the key contributor, as well as a mainstay at the office in all sorts of other, more practical ways (such as deputy editing and proofreading, for example). Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 1, 1997). — J.R.

Buster Keaton is a bachelor who stands to inherit a fortune if he finds himself a bride by seven o’clock in this 1925 silent feature, which Dave Kehr has described as “a cubist comedy…based on a principle of geometric progression” from the number seven. Adapted from a stage-bound play by David Belasco, it takes off into the stratosphere only at the climax, but that outlandish chase sequence alone is well worth the price of admission. On the same program: one of Keaton’s greatest shorts, Cops (1922), which he directed with Eddie Cline. Both films will be shown in 35-millimeter prints, and David Drazin will provide live piano accompaniment. Gene Siskel Film Center, 164 N. State, Friday and Saturday, September 21 and 22, 6:15, 312-846-2800.

Read more

From Oui (August 1974). As unlikely as this may sound to some, Out 1: Spectre enjoyed a week-long run in Paris at a Left Bank cinema (Studio Gît-le-Coeur) in my own neighborhood around the same time I wrote this capsule, so I had many opportunities to make return visits. –- J.R.

Out 1: Spectre. “Who are the 13?” jean-Pierre Léaud, when he isn’t impersonating a deaf mute on Champs-Elysées, is traveling around the rest of Paris, asking a variety of people this embarrassing question. He’s trying to solve the riddle of a secret society alluded to in a coded message – hidden relationships of power and influence lurking behind the normal surfaces of the everyday. Some of the reputed members of this sect include the owner of a hippie boutique (Bulle Ogier), a theater director (Michel Lonsdale), a lawyer (Françoise Fabian), and a novelist (Bernadette Lafont). Meanwhile, a small-time hustler (Juliet Berto) comes across additional evidence in a b atch of letters that she steals for blackmailing purposes. Although Berto and Léaud never meet, just about everybody else in Out 1: Spectre cross paths at one point or another. The movie’s geared to work that way, with each actor furnishing his own scenario and improvising dialogue while Jacques Rivette, the director, stages confrontations between them within his master plan. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, December 1975 (Vol. 42, No. 503). — J.R.

Framed

U.S.A., 1974

Director: Phil Karlson

In films as diverse as 99 River Street and The Phenix City Story, Phil Karlson has shown a striking aptitude for the dynamics of seedy crime melodramas — particularly those which deal, in Andrew Sarris’s phrase, “with the phenomenon of violence in a world controlled by organized evil”. Working, however, in slicker settings and with a plotline at once as hackneyed and as confused as the one in Framed, he appears no better than anyone else at handling the hysterical revenge theme that has often seemed his stock-in-trade.

Discounting some lamentable lab work and five minutes of censor’s cuts in the version under review — which apparently include a rape and some protracted pre-murder mayhem perpetrated by the hero against a failed kidnapper (shooting one ear off and prodding the other with hot wire, until he gives out information) — it is difficult to imagine what could have been salvaged from such a nonsensical collection of plastic characters and cardboard stances, where the narrative proceeds as if by hiccups and the film’s dramatic highlight is provided by the hero remarking of a minor villain, “First time I ever saw a tub of shit in a suit”. Read more

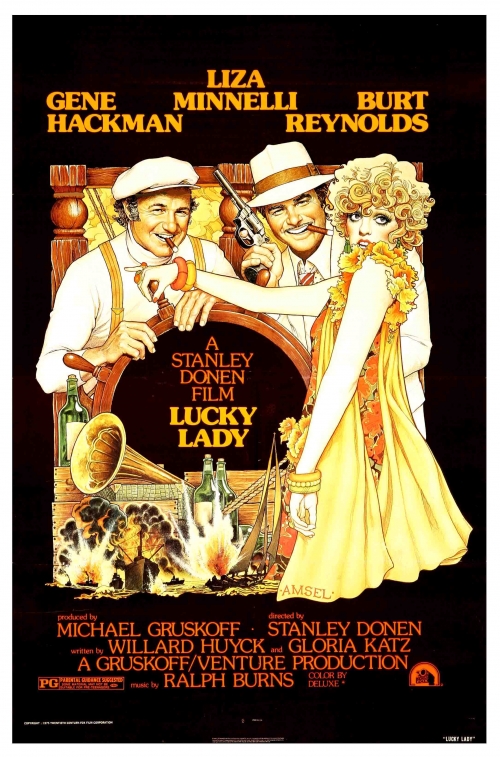

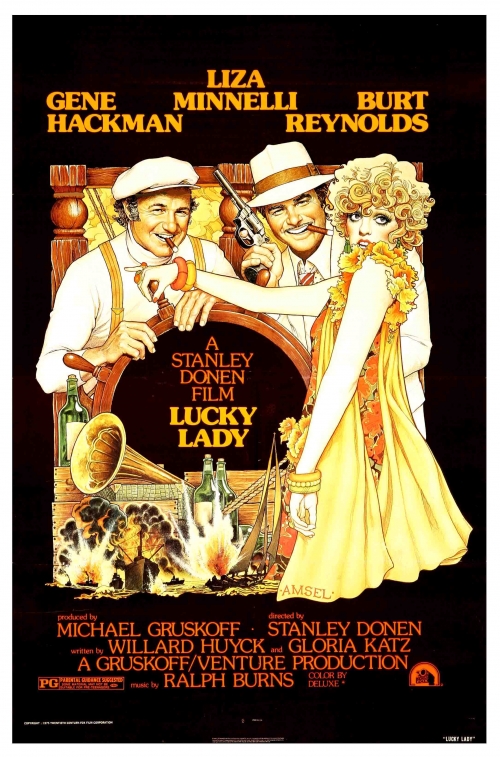

From Monthly Film Bulletin, February 1976 (Vol. 43, No. 505). It’s worth noting that (1) this stinker made a fortune, which suggests that many people must have liked it, and (2) cinemas were required to book it for extended runs regardless of whether or not people showed up or liked it, making it the only movie showing for a lengthy time in many small towns that summer and thus making its profitability a bit of a self-fulfilling prophecy. — J.R.

With an outsized budget estimated variously at $12,600,000 (Variety) and £10,000,000 (Daily Mirror), three box-office favourites and a script deliberately written, according to co-author Gloria Katz, as “the most commercial thing we could think up”, Lucky Lady is both conspicuously overproduced and undernourished.

The presence of Stanley Donen seems to count for little in a project that might more logically have been entrusted to a computer. All it has to express, quite simply, are its deliberations: to combine as many saleable features as can be packed on a screen within the space of two hours. A little of everything is thus tossed into the mixture; and a great deal of nothing emerges out of the isolation and autonomy of the assorted elements. Read more

From Film Comment (July-August 1999). I’ve done a light edit, trimming part of my original conclusion. It’s worth adding that at least two additional pieces about this film have recently turned up on the Internet — a new essay by Ignatiy Vishnevetsky (the first part of an ongoing series) and a detailed account by the late Gilbert Adair that was originally published in 1987, not long after Affaires Publiques was rediscovered in Paris.

I apologize for the poor quality of most of the illustrations from Bresson’s short film, which are the best that I could find. — J.R.

Ten years ago, I flew all the way from Chicago to the San Francisco Film Festival for a weekend to see Robert Bresson’s first film, which had been discovered in incomplete form at the Cinémathèque Française, bearing the title Béby Inauguré. Shorn of three of its musical numbers and now totaling 23 minutes, this rather elaborate piece of slapstick and surrealist tomfoolery was written and directed by Bresson and released in 1934, a full nine years before shooting started on his first feature, Les Anges du péché, and I had been hearing about it for years as an irretrievably lost curiosity. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 28, 2004). — J.R.

Like Mystery Train and Night on Earth, this feature by Jim Jarmusch is a collection of short stories, but it’s funnier and more formally adventurous than either; it’s also ultimately greater than the sum of its parts. Shot in black and white over 17 years, its 11 episodes feature actors and/or musicians, usually playing themselves and hanging out together in cafes while consuming caffeine and nicotine. One recurring theme is the ethics and protocol of being a celebrity (explored most impressively by Alfred Molina and Steve Coogan, and by Cate Blanchett in a virtuoso double role as herself and her own cousin); another is the everyday tension that can develop between friends and relatives. Among the two dozen stars are Isaach de Bankole, Roberto Benigni, Steve Buscemi, GZA, RZA, Bill Murray, Iggy Pop, Bill Rice, Taylor Mead, Tom Waits, and the White Stripes. R, 96 min. Music Box.

Read more

Read more