From Monthly Film Bulletin, February 1976 (Vol. 43, No. 505). It’s worth noting that (1) this stinker made a fortune, which suggests that many people must have liked it, and (2) cinemas were required to book it for extended runs regardless of whether or not people showed up or liked it, making it the only movie showing for a lengthy time in many small towns that summer and thus making its profitability a bit of a self-fulfilling prophecy. — J.R.

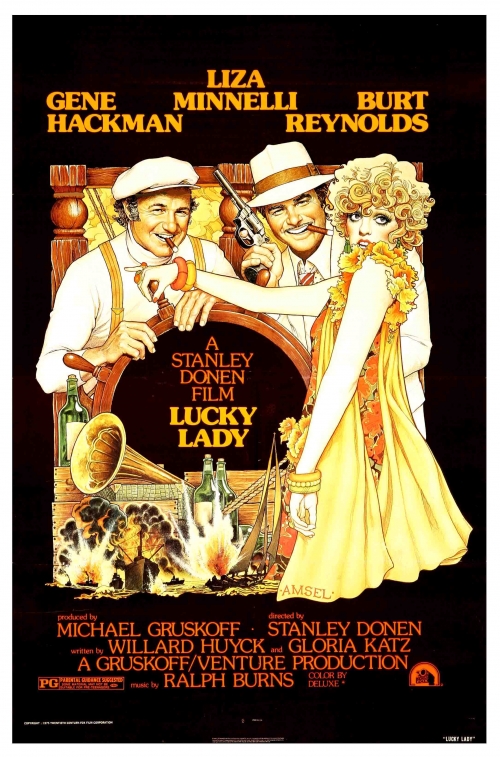

With an outsized budget estimated variously at $12,600,000 (Variety) and £10,000,000 (Daily Mirror), three box-office favourites and a script deliberately written, according to co-author Gloria Katz, as “the most commercial thing we could think up”, Lucky Lady is both conspicuously overproduced and undernourished.

The presence of Stanley Donen seems to count for little in a project that might more logically have been entrusted to a computer. All it has to express, quite simply, are its deliberations: to combine as many saleable features as can be packed on a screen within the space of two hours. A little of everything is thus tossed into the mixture; and a great deal of nothing emerges out of the isolation and autonomy of the assorted elements. For Cabaret-like nostalgia, Geoffrey Unsworth creates a hazy milk-of-magnesia look with a dull sheen that obscures the details of the expensive sets and sea battles, both of which seem to derive from other models.

As the leading lady, Liza Minnelli is dressed in a fright wig worthy of a nightmare dreamt by Robert Aldrich, given two unmemorable songs to sing, and encouraged or allowed to deliver each comic line (sample: “It’s so quiet you can hear a fish fart”) as if she were explaining it to a child of four, crushing gags like so many acorns in her wake. The jolly argumentative ménage à trois reflects an intention to bolster the bantering male duo of The Sting or The Fortune with a small dash of kinkiness (within AA Certificate limits) out of the Bonnie and Clyde cycle, but this in turn has been altered by a last-minute change in casting (Gene Hackman replaced George Segal when the latter became ill), which adds an irrelevant taste of Night Moves to the blend. It is harder to guess at a strategy behind the tinny soundtrack — where all the voices seem to occupy the same disembodied plane — unless one cites a box-office precedent like Deep Throat or The Night Porter; but Burt Reynolds’ rendition of “Ain’t Misbehavin’ ” with a 78 r.p.m. record does suggest a possible fusion of At Long Last Love and Lady Sings the Blues. The absence of any ruling principle that might unify such combinations is sadly reflected in the public protest lodged by Liza Minnelli and Burt Reynolds against Donen’s decision to change the movie’s ending, which originally had the two male leads killed by federal agents.

According to Minnelli, “The changes made in the film mark the difference between a work of art and a commercial movie” — an astonishing notion in relation to the film as it now stands, which could end a dozen different ways without substantially altering anything. If, however, it had concluded with the entire fleet of battling ships and all the characters consumed by one enormous tidal wave, thereby assimilating the disaster film and the science fiction epic into its strategies, it might have broadened its horizons far enough to encompass a few moments of old-fashioned entertainment.