From the Chicago Reader (August 27, 1993). — J.R.

MANHATTAN MURDER MYSTERY

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Woody Allen

Written by Allen and Marshall Brickman

With Allen, Diane Keaton, Alan Alda, Anjelica Huston, Jerry Adler, Joy Behar, Ron Rifkin, and Lynn Cohen.

It’s instructive to divvy up Woody Allen’s movies into “art films” and entertainments. Without too much boiling and scraping, I think you could say that the entertainments come from his first 11 years as a filmmaker, from What’s Up, Tiger Lily? (1966, now missing from the press-kit filmography) to Annie Hall (1977), while his art-film efforts extend from Interiors (1978) to Husbands and Wives (1992).

Some would argue that Broadway Danny Rose (1984) and The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985), coming halfway through the second period, belong to the entertainment category, along with “Oedipus Wrecks” (1989), his contribution to New York Stories, but I would beg to differ. (The first of these is in black and white, the second traffics in misery and pathos, and the third derives directly from Fellini’s episode in Boccaccio ’70 — the first pieces of counterevidence I’d cite.) Similarly, to those who’d claim that the “foreign movie” sketch in Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex (But Were Afraid to Ask) (1972) pushes it into the art-movie category, I’d maintain that there’s a world of difference between this film’s parody of Antonioni and the pastiches of the later movies.

I’m not trying to argue that Allen’s 16 “art” features aren’t entertaining, only that it’s mainly a constipated and superficial notion of what art is that authorizes what makes them entertaining. I’d even claim that only in a country that hates and fears art as much as this one does — a country that allots more federal funding to military marching bands than to all its artists combined — could a gifted writer and entertainer like Allen be catapulted to the status of a major artist.

As far as most critics are concerned, the turning point wasn’t Interiors but Manhattan (1979), the film that immediately followed it. Here at last was a movie that flattered and rewarded (while gently tweaking) the self-image of upscale urbanites so effectively that critics all but anointed Allen our official poet laureate out of sheer gratitude. Writing about the movie from Cannes in 1979, English critic Penelope Houston caught the zeitgeist perfectly: “A funny, nervous, garrulous, New Yorkerish picture, everything that one would expect of its maker and certainly a little more, it floats in on an advance wave of American ecstasy (‘The only truly great American film of the 70s’ — Andrew Sarris). You can sense the audience in the Palais purring with pleasure as Gordon Willis’s splendid black and white camerawork probes the skyline, and the Gershwin tunes suggest that if we wait long enough Fred and Ginger might even round a street corner. . . . The film’s accuracy in catching a New York setting of neurosis and cultural gush and underlying despair, where even the analysts (or perhaps especially the analysts) have lost their wits, seems undoubted; and bound to appeal especially to the New York critics, as comforting assurance that the world they inhabit really exists.”

If this wasn’t art, the zeitgeist seemed to be saying, it would do just fine until the real thing came along. So it wasn’t too surprising that this witty comic and devoted copycat came to occupy more or less the same cultural niche as his primary models, Bergman and Fellini. (Bergman’s retirement from filmmaking and the failure of many Fellini films, including one called Ginger & Fred, to get much or any U.S. distribution only helped this process along.) While a genuine inventor of forms like Samuel Fuller (who doesn’t conform to the mousy image of the cloistered artist this country finds so heartening) was being forced into exile to find work, Allen was being celebrated as our official idea man, our metaphysical sage — the perfect artist for an audience as nervous as he is about the very notion of art.

Allen’s return to his entertainment mode in Manhattan Murder Mystery has been receiving some mixed press — in part because it occurs in the shadow of his break with Mia Farrow and the ensuing custody scandals, which have tarnished his image for some; in part because even Allen has been cautioning us not to take the movie too seriously. For me, it’s ample cause for breaking out a magnum of champagne.

While the movie is no masterpiece, it represents both a significant (albeit tentative) advance in Allen’s work as art and an agreeable (if uneven) return to his practice of “simply” entertaining. Which is to say it’s less successful than Annie Hall but more provocative than Crimes and Misdemeanors — and certainly a lot funnier than Shadows and Fog. A middle-aged romance that cunningly uses an intricate and clever mystery plot to spike its main course, it may represent the first time in Allen’s career that stepping beyond the rigid class barriers that define his familiar upscale world is regarded as sexually exciting — a walk on the wild side that ultimately rejuvenates a stagnating marriage. It also benefits from the delightful return of Diane Keaton as a flaky, adventurous muse to Allen, an impulsive risk taker who eventually pulls him out of his whiny, constricted universe.

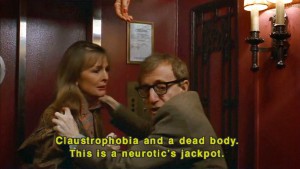

It takes a while before the class implications of the adventure become evident, but some notion of what’s in store is already apparent when we see Larry and Carol Lipton (Allen and Keaton) returning to their comfortable high rise from a hockey game, she with the New York Daily News and he with the Sunday Times. They start to chat in the elevator with Paul and Lillian House (Jerry Adler and Lynn Cohen), the older couple who live directly across the hall, and in spite of Larry’s reluctance — he wants to watch an old Bob Hope movie on TV — Carol accepts the Houses’ invitation to come over for a drink. Afterward she muses, “Will we become another dull aging couple like that?” (We’re treated to several gags about how unglamorous the Houses are, especially Larry’s displays of boredom with Paul’s stamp collection and Lillian’s exercise program.)

A day or so later, after a trip to a flea market and going to see Double Indemnity, Larry and Carol come home to the news that Lillian has dropped dead from what a doctor describes as a “classic coronary.” But before long Carol becomes suspicious about the cause of the death and the “perky” behavior of the husband; after Larry scoffs repeatedly at her doubts, she finds a more receptive ear when she phones Ted (Alan Alda), a playwright friend. Eventually this develops into some amateur sleuthing on her part a la Rear Window — filching an extra key to the House flat from the super, sneaking inside to look for incriminating evidence when Paul is out, calling Ted from there to report on her progress, and then hiding under a bed when Paul makes an unexpected return. Larry, who works as an editor at HarperCollins, is meanwhile developing a mild flirtation with Marcia Fox (Anjelica Huston), one of his authors, whose latest novel is entitled Comfort Zones.

It’s a simple enough setup, and it develops class tensions only after we’re regaled with the usual consumerist inventory of glamorous yuppie hangouts (Elaine’s, Lincoln Center, posh restaurants, et al). Meanwhile, we get further escapades in the House flat, some flirtation between Ted and Carol, Carol’s sighting of the supposedly dead Lillian in a passing bus, and more sleuthing with Ted — including an incognito visit to a ramshackle movie theater Paul owns and is planning to restore — that finally leads them to a downscale hotel. At this point Larry, who’s been spending more time with Marcia, finally joins Carol in the detective work (“We’re on the threshold of a real experience”), and still further adventures lead the couple to drive out of Manhattan to a seedy warehouse district, where they see a corpse being dumped into molten steel.

Anything that gets a Woody Allen couple out of Manhattan is surely enough to make one sit up and take notice. Larry and Carol’s subsequent trip to meet Ted and Marcia (who are by now becoming a couple) at a New Jersey bar in the middle of the night only confirms the new direction in their marriage — and the hint of a new direction in Allen’s work. (That this “walk on the wild side” is strictly voyeuristic goes without saying, but so is the obligatory catalog of yuppie hot spots that preceded it.)

Another part of this new direction can be felt in the peregrinations of the mainly hand-held camera — meandering between and around the characters, who are often viewed from a relative distance. Some viewers have been complaining about this complicated busywork — which superficially resembles the wandering camera movements and deliberate “bad” cuts in Husbands and Wives, Allen’s previous picture — and a couple within my earshot maintained that it gave them headaches. For me it’s one welcome sign that the complacency and security of Allen’s congested manner are finally being cut loose from their moorings, and if this entails a loss of the visual coddling that made his arty movies so insular, so much the better. It could be argued that this jumpy camera style is every bit as mannerist as the Bergman-esque still lifes than preceded it, but it has the formal virtue of providing a sort of loose obbligato to the tightly rehearsed overlapping dialogue. Like the jazz recordings used in the score, it provides a feeling of improvisation in relation to the fixed itineraries of the script.

While film references are anything but absent from this movie, they’ve shifted in their nature and function. For once, virtually all the key references are to Hollywood movies — Bob Hope mystery comedies, Double Indemnity, Rear Window, The Lady From Shanghai — and their function is mainly to make thematic points rather than to provide arty surfaces and blue-chip calling cards. (Significantly, the latter three movies are fundamentally concerned with class tensions and the relationship between sex and money.) The only partial exception to this — a climactic use of the fragmented house-of-mirrors shoot-out from The Lady From Shanghai that deliriously extends the arty fragmentation of the original with mirrors of its own — is so nicely executed that I can forgive the cornball gloss it’s accorded afterward in the dialogue. And it might even be argued that an earlier verbal reference to the non-Hollywood Last Year at Marienbad points to a picture about “dangerous seduction” that plays throughout with Hollywood conventions.

Not everything works or is accounted for. Larry and Carol have a son enrolled in Brown (Zach Braff) whom we see once or twice, but he’s neither integrated into the plot nor represented in a way that makes us believe the lead couple are parents. Some of the thriller moves are handled awkwardly, and the characterizations of Ted and Marcia are perfunctory at best. A few of the plot maneuvers — notably a scene involving four cassette recorders — are simply pretexts for gags. But Allen’s willingness to let Keaton steal the movie from him gives me some hope that one of the most overpraised artists of our time — our perennial badge of middle-class insularity — may finally be creeping out of his cocoon.