Written for the catalogue of Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna (June-July 2017). — J.R.

It might be excessive to claim that The Asphalt Jungle (1950) invented the heist thriller (also known as the caper film), but at the very least one could say that it provided the blueprint for the most successful examples of that subgenre that would follow it, including (among others) The Lavender Hill Mob (1951), Rififi (1955), The Killing (1956), Seven Thieves (1960), The Thomas Crown Affair (1968), and Reservoir Dogs (1992) — not to mention such parody versions as Big Deal on Madonna Street (1958) and most of the latter films of Jean-Pierre Melville, including Bob le flambeur (1956), Le deuxième souffle, (1966), and Le cercle rouge (1970). Indeed, The Asphalt Jungle was regarded as such a master text by Melville that one isn’t surprised to find over a dozen references to it in Ginette Vincendeau’s book about him. According to Geoffrey O’Brien, Melville once “declared that…there were precisely nineteen possible dramatic variants on the relations between cops and crooks, and that all nineteen were to be found in [John Huston’s masterpiece].”

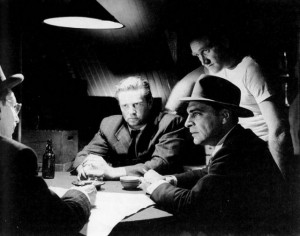

In short, the reverberations in this MGM A-feature are multiple, although that doesn’t prevent it from still seeming fresh today. Adapted by Ben Maddow and director John Huston from a 1949 novel by W. R. Burnett (Little Caesar, High Sierra), it’s especially memorable for its gallery of small-time hoodlums in an unnamed Midwestern city who are enlisted in the planned caper: a bookie (Marc Lawrence), Kentucky-bred compulsive gambler (Sterling Hayden), lawyer (Louis Calhern), safecracker (Anthony Caruso), hunchbacked getaway driver, and a mastermind fresh out of prison (Sam Jaffe) who plans the jewel robbery. There are also memorable turns by Jean Hagen as Hayden’s girlfriend, Marilyn Monroe as Calhern’s mistress, and Dorothy Tree as Calhern’s wife. Promoting the film when it came out, Huston described each member of the gang as having a separate vice, and this is what also makes each of them life-sized. No less impressive are Miklós Rózsa’s characteristically brazen score and Harold Rosson’s glittering cinematography.

Jonathan Rosenbaum