This was written in the summer of 2000 for a coffee-table book edited by Geoff Andrew that was published the following year, Film: The Critics’ Choice (New York: Billboard Books). — J.R.

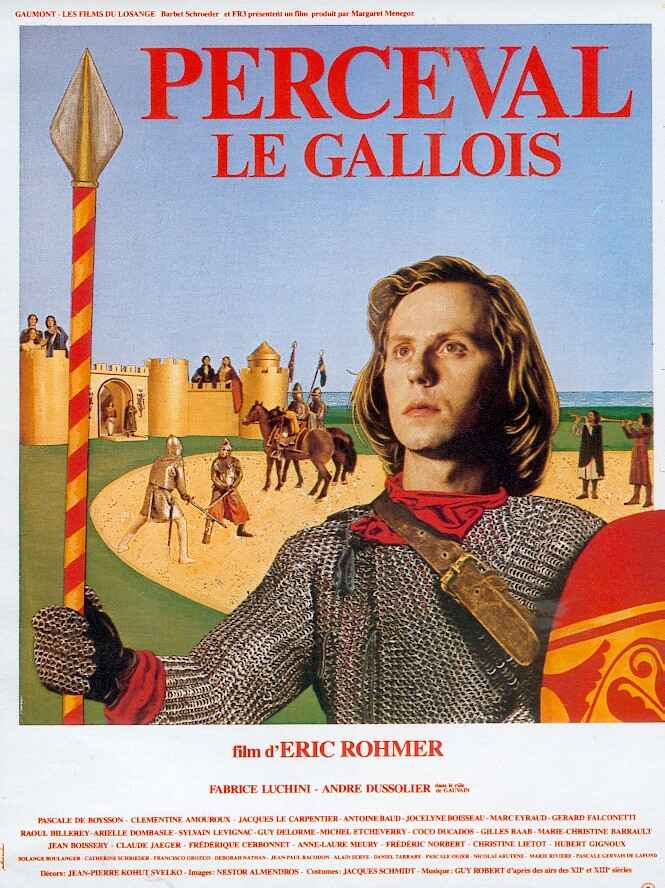

Eric Rohmer’s least typical film, Perceval might also be his best: A wonderful version of Chrétien de Troyes’ 12-century epic poem, set to music, about the adventures of a callow and innocent knight (Fabrice Luchini). Deliberately contrived and theatrical in style and setting -– the perspectives are as flat as in medieval tapestries, the colors bright and vivid — the film is as faithful to its source as possible, given the limited material available about the period.

Luchini, who would later play Octave in Rohmer’s much more characteristic Full Moon in Paris (1984), called Perceval “a scholarly project, touched by insanity.” That is both its charm and its ineffable strangeness, enhanced by the fact that it represents an almost complete departure from the carefully crafted realism of Rohmer’s other films. As Australian critic G.C. Crisp has described this realism, “The cinema is a privileged art form because it faithfully transcribes the beauty of the real world….Any distortion of this, any attempt by man to improve on [God’s handiwork], is indicative of arrogance and verges on the sacreligious.”

Though this might seem to make Pervecal a betrayal of Rohmer’s aesthetic, his medieval musical -– which actually feels at times like a studio-shot Western, complete with artificial sky -– cogently illustrates his stated conviction as a critic that a true preservation of the past ultimately produces a kind of modernity. (Working against the grain of anything that might be regarded as quaint or old-fashioned in the film is the immediacy of the violence and the utter lack of sentimentality). When asked [by me] how he reconciled his realist aesthetic with this film, Rohmer responded by recalling André Bazin’s defense of Carl Dreyer’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc as a realist work: that at least the dirt in that film was real. Here, where there doesn’t appear to be any dirt at all -– and where the film’s settings often seem to resemble the artificial greens of miniature golf courses -– it still might be argued that it is actually the 12th century that emerges as real. And the merit of this realism is that it brings something otherwise dead and forgotten to life -– not because Rohmer’s imagination is especially rich but because he can see no alternative to his literalism, even if it makes some viewers laugh in disbelief.

One striking example of the literalism is the fact that Rohmer’s fidelity to the text compels him to include narrative descriptions as well as dialogue in the sung passages. The film opens with musicians and singers who also manufacture bird sounds, and members of this entourage periodically follow the characters around, making further comments. Among those followed are actors Rohmer would memorably use again, including André Dussollier (Le beau marriage, 1981) and, making their debuts, Arielle Dombasle (Pauline at the Beach, 1983) and the late Pascal Ogier (Full Moon in Paris, 1984).