From the Chicago Reader (November 10, 2000). — J.R.

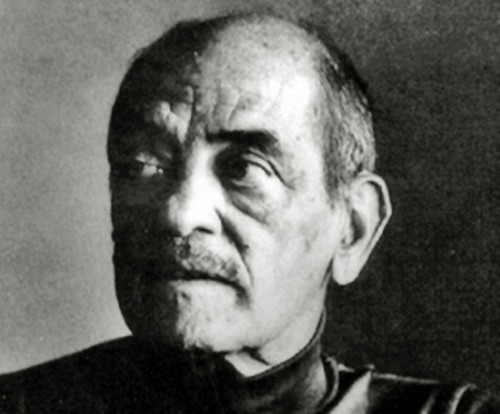

Films by Luis Buñuel

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

It seems to be universally agreed that Luis Buñuel (1900-1983) is the greatest Spanish-language filmmaker we’ve ever had, but getting a clear fix on his peripatetic career isn’t easy. The authorized biography, John Baxter’s 1994 Buñuel, isn’t available in the U.S., and the deplorable English translation of Buñuel’s autobiography, My Last Sigh (1983), is actually an unacknowledged condensation of the original French text. Better are an interview book translated from Spanish, Objects of Desire, and a recently published translation of selected writings by Buñuel in both Spanish and French, An Unspeakable Betrayal, which includes his priceless, poetic early film criticism.

A more general problem is that Buñuel is not only “simple” and direct but full of teasing, unresolvable ambiguities. A master of the put-on, he often impresses one with his earthy sincerity. A political progressive and unsentimental humanist, he was also, I’ve learned from Baxter, an active gay basher in his youth, and those who’ve read the untranslated but reputedly fascinating memoirs of his widow report that he was a very old-fashioned and prudish male chauvinist throughout his life. He was a onetime devout Catholic who lost his faith in his youth and was fond of exclaiming years later, “Thank God I’m still an atheist!” Read more

These two short articles were written for the catalogue of the fifth edition of the Buenos Aires Festival of Independent Film in 2004. Both are about neglected filmmakers who are or were also longtime friends of mine–although neither, to the best of my knowledge, has ever seen any films by the other, and they met for the first time at the festival, where complete retrospectives of both filmmakers were being presented. (I first met Eduardo in Paris in 1973, shortly after he’d finished working as a screenwriter on Jacques Rivette’s Céline et Julie vont en bateau, and I first met Sara about ten years later in New York, shortly before I saw her first major film, You Are Not I, and decided to devote a chapter to her in my book Film: The Front Line 1983.) Her complete works apart from her 2017 Boom for Real: The Late Teenage Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat are now available in a wonderful two-disc package, which can be found here.

When I was asked to write these two pieces for the BAFICI catalogue, I opted to make them each exactly the same length (942 words) and to make them rhyme with one another in various other ways. Read more

This was written exactly one week after September 11, 2001, at the invitation of the Chicago Reader‘s editor, but the first time it was published was on this web site on March 11, 2010. — J.R.

I was having breakfast in the restaurant of my Toronto hotel on September 11 when I heard President Bush on TV making his first statement of that day, from Florida. I saw the World Trade Center towers in flames, but it wasn’t until I resumed watching the coverage in the film festival’s press office a few blocks away that I actually saw them fall. It was an event that registered in increments for the remainder of the day and the remainder of the week — something that’s still going on. And evaluating whether the prospects of adjusting to the shock and horror are grim or hopeful seems largely a matter of thinking in short or long terms.

***

“Pearl Harbor” as a reference point is a good example of the grimmest and least helpful short-term thinking, literally predicated on a world that hasn’t existed for 60 years. (One variation, sadly coming from one of my brightest and most progressive friends: to compare what we’d like to do to Osama bin Laden and other terrorists to what we did to the Japanese, by dropping Atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki — i.e., Read more

From the Chicago Reader (August 14, 1997). — J,R.

Adapted by Ann Biderman from the popular Peter Hoeg novel and directed by Bille August (Pelle the Conqueror, The Best Intentions), this is a watchable conspiracy thriller, but, as with most conspiracy thrillers, the first half is a lot more watchable than the second: the more one discovers, the less interested one becomes. Playing a troubled and not very likable loner who’s half Greenlandic Inuit and half American, Julia Ormond—a lot more interesting here than she’s been on previous star outings—plays a spiky recluse obsessed with solving the mystery of the allegedly accidental death of a six-year-old Inuit neighbor. This leads to a complex investigation whose facts become steadily more outlandish. Others in the cast include Gabriel Byrne, Richard Harris, Robert Loggia, and, in a cameo, Vanessa Redgrave. Jorgen Persson’s ‘Scope cinematography is handsome; the imitation Bernard Herrmann score is by composer-by-the-yard Hans Zimmer, working with Harry Gregson Williams.

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 1, 1993). — J.R.

A stunning debut (1992) from writer-director Quentin Tarantino, though a far cry from Stanley Kubrick’s 1956 The Killing, to which it clearly owes a debt. Like The Killing, it employs an intricate flashback structure to follow the before and after of a carefully planned heist and explores some of the homoerotic allegiances, betrayals, and tensions involved; unlike The Killing, it never flashes back to the heist itself and leaves a good many knots still tied at the end. The hoods here — including Harvey Keitel, Tim Roth, Michael Madsen, Steve Buscemi, and (in a bit) Tarantino himself — are all ex-cons hired by an older ex-con (Lawrence Tierney) who conceals their identities from one another by assigning them the names of colors. Our grasp of what’s going on is always in flux, and Tarantino’s skill with actors, dialogue, ‘Scope framing, and offbeat construction is kaleidoscopic. More questionable are the show-offy celebrations of brutality: buckets of blood, racist and homophobic invective, and an excruciating sequence of sadistic torture and (offscreen) mutilation that’s clearly meant to awe us with its sheer unpleasantness. It’s unclear whether this macho thriller does anything to improve the state of the world or our understanding of it, but it certainly sets off enough rockets to hold and shake us for every one of its 99 minutes. Read more

Published by DVD Beaver in April 2006. I’ve updated this to include further links for films that have subsequently become available; there are in fact quite a few of these, and, unless I’ve missed something, only one title that isn’t currently available, The Argyle Secrets. — J.R.

Most of my favorite offbeat musicals are commercially available on DVD, and I wrote about them for DVDBeaver in March. I can’t say the same about most of my favorite noirs, and I’m not sure why this is so.

It’s also important to stress that “noir” isn’t a genre; it’s a category that’s applied retroactively to films with certain traits in common — a practice started by French critics and eventually continued by us Yanks and others. (Check out James Naremore’s definitive 1998 book on the subject, More Than Night: Film Noir in its Contexts.) This makes it something more flexible than a genre, and I’ve tried to honor this factor in some of my choices.

In the following list I’ve managed to make peace with myself by appending one SBA title (which stands for “should be available”) to each one that you can currently buy, in the same general category, with brief explanations added. Read more

From Projections 8, edited by John Boorman and Walter Donohue, 1998. Subtitled Film-makers on Film-makers, this issue of the periodic Faber and Faber publication was devoted specifically to what it called ‘criticism,’ spurred jointly by a brief declaration by Bruce Willis at Cannes in 1997 (‘Nobody up here pays attention to reviews…most of the written word has gone the way of the dinosaur’) and a lengthy essay by François Truffaut, ‘What Do Critics Dream About?’, introducing his 1974 collection The Films of My Life. As nearly as I can remember, I was one of the nine critics (along with Gilbert Adair, Geoff Andrew, Michel Ciment, Peter Cowie, Kenneth Turan, Alexander Walker, Armond White, and Jonathan Romney) asked to respond to these two declarations of principles. (I haven’t been able to find Truffaut’s essay online, but an excerpt from it can be found here: https://www.lostinthemovies.com/2009/04/what-do-critics-dream-about.html.)

If my comments about the Truffaut essay sound harsh, I hasten to add that I still regard his early criticism as seminal — perhaps even the most seminal that was written by Bazin’s younger disciples, as Godard, among others, has suggested. -– J.R.

I welcome the prospect of an issue of Projections devoted to `the art and practice of film criticism’, though given the present climate that circulates around film discourse in general — a climate at once pre-critical and post-critical in which the static produced by commerce tends to drown out most of the murmurs associated with criticism — I’m more than a little fearful about what results such an inquiry is likely to yield. Read more

Written for Sight and Sound (March 2017). — J.R.

WE’LL ALWAYS HAVE CASABLANCA

The Life, Legend, and Afterlife of Hollywood’s Most Beloved Movie

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

By Noah Isenberg. W.W. Norton & Co., 334 pp. US$27.95. ISBN 9780393243123.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Reviewed by Jonathan Rosenbaum

I’ve never been asked to select my favourite ‘guilty pleasures’ in movies, but I suspect that if I were, Gone With the Wind and Casablanca — two highly accomplished and engrossing pieces of dubious Hollywood hokum — could easily head the list. Yet it’s one of the signal virtues of Noah Isenberg’s We’ll Always Have Casablanca to suggest that the true sources of Casablanca’s popularity place it well beyond the racial and racist subtexts of Gone With the Wind.

In the case of the latter film, we have the benefit of Molly Haskell’s Frankly, My Dear (2009), a superb critical and ideological unpacking of both the Margaret Mitchell novel and the David O. Selznick blockbuster. Isenberg, an academic and a scholar more than a critic — director of screen studies and professor of culture and media at New York’s New School, and best known among cinephiles as an Edgar G. Ulmer specialist — hasn’t given us the same sort of book as Haskell, although he’s produced a volume that’s equally accessible and nearly as valuable in explaining the appeal of a popular classic. Read more

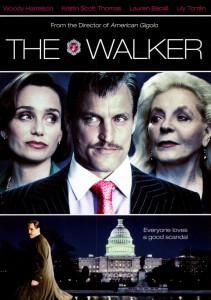

From the Chicago Reader (October 5, 2007). — J.R.

“Has there ever been a good Paul Schrader film?” a colleague asked me on my way into the press screening for this feature, the director’s 16th. I haven’t seen quite all of them, but I couldn’t come up with a single title, even though some have their compensations (Patty Hearst, Light Sleeper). As does this weak thriller, about a gay southern dandy (Woody Harrelson) who escorts aging society ladies around Washington, D.C., and becomes the prime suspect when the lover of one gets murdered. The main compensation is Harrelson’s well-judged and finely shaded performance; the secondary ones are the ladies he hangs out with — Lauren Bacall, Lily Tomlin, and Kristin Scott Thomas. But the rest of this mainly drifts. R, 107 min.

Read more

Read more

My contribution to the 2019 anthology Unwatchable, published by Rutgers University Press and edited by Nicholas Baer, Maggie Hennefeld, Laura Horak, and Gunnar Iversen. — J.R

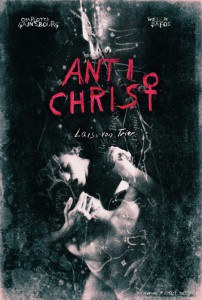

My refusal to watch Lars von Trier’s Antichrist (2009), even after Criterion generously sent me a review copy, isn’t a position I arrived at suddenly or lightly. Even though the film premiered the year after I retired as a weekly reviewer, thus obviating any possible professional obligation, my decision wasn’t only based on the near-certainty that I would hate it — which, after all, hadn’t prevented me from twitching all the way through The Passion of the Christ five years earlier. Nor was it founded on any conviction that von Trier is devoid of talent, a conviction I don’t have.

Trying retroactively to account for my steadfast refusal to see the film, arrived at eight years ago, I can only take the blatantly ahistorical, illogical, and quintessentially Trieresque tack of citing a remark of his quoted in the Guardian only six months ago. It concerns his latest project (I won’t assist his ad campaign by mentioning the title) — a feature about a serial killer (natch) that takes the serial killer’s viewpoint (ditto). It’s a film, he says, that “celebrates the idea that the life is evil and soulless, which is sadly proven by the recent rise of the Homo trumpus —the rat king. Read more

From Film Quarterly (Winter 2008-09: Volume 62, Number 2). — J.R.

It’s been gratifying to see the almost instant acclaim accorded to John Gianvito’s beautiful, 58-minute Profit Motive and the Whispering Wind (2007), especially after the relative neglect of his only previous feature-length film, the 168-minute The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein (2001).

The more recent film — a meditative, lyrical, and haunting documentary about grave sites that won the grand prix at the Entervues Film Festival in Belfort in 2007 and both a Human Rights Award and a special mention at the Buenos Aires Festival of Independent Film in 2008 —- also received an award at the Athens International Film and Video Festival in Ohio and was named the year’s best experimental film by the National Society of Film Critics. (Full disclosure: I nominated Profit Motive for the last of these awards, and headed the jury of the same Buenos Aires film festival in 2001, which gave The Mad Songs its top prize.)

The Mad Songs focuses on the irreparable effects of the first Gulf war in 1991 on three separate powerless people in New Mexico (which is where the film in its entirety was shot). Profit Motive focuses on the grave sites of several dozen heroes of progressive struggles throughout American history. Read more

From Jean-Luc Godard: Son-Image 1974-1991 (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1992). -– J.R.

“Jean-Luc cultists,” complains Judith Crist in the World Journal Tribune. God bless them! They constitute a line of defense against every manipulative insult the entertainment business throws out, there are more of them each year, and they may even be winning. — Roger Greenspun (1)

Greenspun’s rallying cry of a quarter of a century ago testifies to the passion and debate that used to be stirred up in the United States when Godard’s name was mentioned. The gradual phasing out of that debate and the depletion of that passion cannot be explained simply, and to understand it at all requires some careful thought about how American culture as a whole has itself changed in the interim. For a director still closely identified with the sixties in American film criticism, Godard is regarded today with much of the same fear, skepticism, suspicion, and impatience that greet many other contemporary responses to that decade. And his status as an intellectual with a taste for abstraction may make him seem even more out of place in a mass culture that currently has little truck with movie experiences that can’t be reduced to sound bites. Read more

Can I help promote a collection of symposia, two of which I participated in, as well as several interviews? Why not? This is fun to browse and useful as well as instructive to read. The symposia are conducted with exemplary breadth and thoroughness (the one on international film criticism, for instance, takes in no less than twenty countries), and although the interviews are mostly with critics (Pauline Kael, John Bloom, Peter von Bagh, Mark Cousins), a good many programmers and film preservationists are also surveyed. Editors Cynthia Lucia and Rahul Hamid have done a careful and conscientious job and produced a very handsome book. Need I say more? [12/16/17] Read more

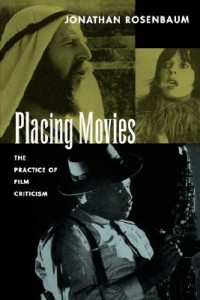

This is the Introduction to the first section of my first collection, Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (University of California Press, 1993). I’ve taking the liberty of adding a few links to some of the pieces of mine mentioned here which appear on this web site. — J.R.

Introduction

Although this entire book is devoted to film criticism as a practice, this section emphasizes this fact by dealing with film criticism directly as a subject. This includes both specific examinations of the work of other critics and polemical forays into questions about how critics and reviewers operate on a day-to-day basis. A broader look at the same topic might question whether film criticism as it’s presently constituted is a worthy activity in the first place — if in fact the public would be better off without it.

I should add that it’s the institutional glibness of film criticism in both its academic and mainstream branches — above all in the United States, where it seems most widespread and least justifiable — that has led me on occasion to raise this latter question. Speaking as someone who set out to become a professional writer but not a professional film critic, I’ve never felt that movie reviewing was an especially exalted activity, but I didn’t start out with any contempt or disdain for the profession either. Read more

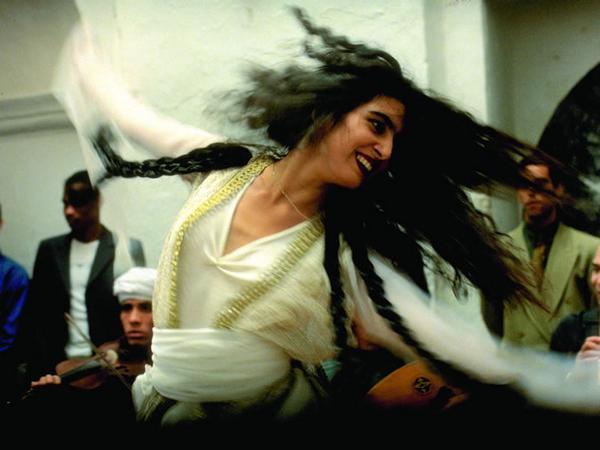

From the Chicago Reader (February 10, 1995). –J.R.

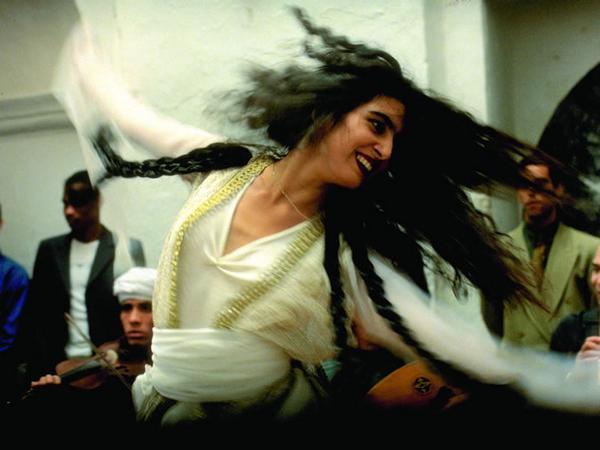

Latcho Drom

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed and written by Tony Gatlif.

If you haven’t heard of Latcho Drom — an exuberant and stirring Gypsy musical, filmed in CinemaScope and stereophonic sound in eight countries on three separate continents — you shouldn’t be surprised. Although the movie has been wending its way across the planet for the past couple of years and picking up plenty of enthusiasts en route, it has at least three commercial strikes against it, any one of which would probably suffice to keep it out of the mainstream despite its accessibility. The first two of these are the words “Gypsy” and “musical”; the third is the fact that it qualifies as neither documentary nor fiction, thereby confounding critics and other packagers.

These “problems,” I hasten to add, are what make the picture pleasurable, thrilling, and important; but media hype to the contrary, sales pitches and audience enjoyment aren’t always on the same wavelength. Though this movie is so powerful you virtually have to force yourself not to dance during long stretches of it, that fact doesn’t translate easily into a 30-second prime-time spot or a review in a national magazine (though CNN did devote a four-minute feature to Latcho Drom some time ago). Read more