This was written exactly one week after September 11, 2001, at the invitation of the Chicago Reader‘s editor, but the first time it was published was on this web site on March 11, 2010. — J.R.

I was having breakfast in the restaurant of my Toronto hotel on September 11 when I heard President Bush on TV making his first statement of that day, from Florida. I saw the World Trade Center towers in flames, but it wasn’t until I resumed watching the coverage in the film festival’s press office a few blocks away that I actually saw them fall. It was an event that registered in increments for the remainder of the day and the remainder of the week — something that’s still going on. And evaluating whether the prospects of adjusting to the shock and horror are grim or hopeful seems largely a matter of thinking in short or long terms.

***

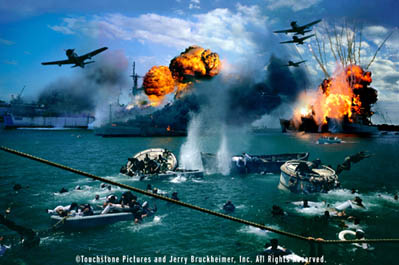

“Pearl Harbor” as a reference point is a good example of the grimmest and least helpful short-term thinking, literally predicated on a world that hasn’t existed for 60 years. (One variation, sadly coming from one of my brightest and most progressive friends: to compare what we’d like to do to Osama bin Laden and other terrorists to what we did to the Japanese, by dropping Atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki — i.e., getting them to stop. My friend didn’t suggest which particular targets and how many innocent victims he contemplated, but I’m sure he didn’t count himself or his family as part of the “necessary” collateral damage.)

I assume it was Pearl Harbor that came to so many minds rather than the sinking of the Titanic (“the symbol of the might of the 19th century industrial civilization,” as Slavoj Zizek has recently noted) because the movie Pearl Harbor opened four months ago whereas the movie Titanic opened four years ago. “Steven Spielberg has a lot to answer for,” a colleague said to me earlier this week, and I knew exactly what she meant. Positing World War 2 as an apt parallel for what’s happening now borders on the psychotic because we aren’t entering a world war — though we may be in serious danger of starting one by launching a CNN-style apocalypse even before we have a clearly identified enemy or target, just a logo and a desire to kick some non-American ass. Driving home from work today to write this piece, I heard speculations on the radio about going after bin Laden and attacking Afghanistan, though a government official was quoted as saying, “Afghanistan doesn’t have a lot of high-value targets.” In other words, only low-value people who are already suffering deeply, along with a lot of rubble — which suggests we may place an even lower value on innocent human lives than bin Laden does. The announcer, recalling the miseries of the Russian occupation of Afganistan and the likely futility of a land war, added that of course we probably wouldn’t capture bin Laden anyway — reminding me of the statements of other government officials which come close to implying that if we can’t find him, any other Arab will do. (Idle query: why is it that the three most demonized figures in this country’s recent war mythology — Noreiga, Saddam, bin Laden — are all largely American inventions whom we previously contrived to jockey into position? If they’re as evil as the Bushes claim — and I’m not inclined to doubt them — what does this say about Bush senior and the others who initially empowered them? Maybe this might help to explain why we seem to adopt some of their own worst qualities once we decide to pursue them.)

Pearl Harbor was attacked in 1941 by an enemy nation. We still have no evidence that the terrorist attacks of September 11 came from any nation at all, but if we insist on acting as if they did, it’s questionable whether we’re much different from those terrorists — who “equated” us Americans with such symbols of global aggression as the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Maybe we’re different only in the sense that the terrorists’ monstrous act was a clear statement — a response to U.S. brutality that could be read and understood across the planet and was something that 18 individuals were willing to sacrifice their lives in order to utter — while most of the statements our leaders have made so far are delusional forms of denial, designed, as Susan Sontag has recently noted, more as psychotherapy than as “the politics of a democracy — which entails disagreement, which promotes candor”. Calling these terrorist acts “cowardly” is as idiotic as threatening to bomb any country that “harbors” their perpetrators — an undertaking that would obviously have to start with this country, which “harbored” all 18 of the perpetrators and may well be “harboring” others who are still alive. Claiming, moreover, that they committed this act simply because they “hate freedom” goes well beyond presumption and stupidity into a refusal to acknowledge basic reality — namely, what this country has been doing to innocent people in the Middle East since the 1980s, and what it’s preparing to do to other “low-value” (i.e., non-American) human targets at the moment. Maybe Bush means the freedom to bomb the hell out of non-Americans regardless of whether or not they’re guilty of anything. Apparently doing this makes some people feel good — people who have been spending much of the past week presuming to speak for the rest of us.

***

“Collateral damage” is a popular phrase these days; it’s even the title of an Arnold Schwarzenegger/Andrew Davis opus about Middle Eastern hijackers and terrorists that was scheduled to open the Chicago International Film Festival this Thursday, until the studio sensibly decided to withdraw it. (Its replacement is a David Mamet opus called Heist.) Despite the fact that this festival’s lineup promises to be one of the best it has had in many years — with pungent glimpses into the world around us that seem more necessary to our survival than ever before — the sheer moral tackiness of the star-hunger that led to anyone wanting to show a film like Collateral Damage in the first place is difficult to shake off.

Needless to say, cartoon Middle Eastern hijackers and terrorists have been as much a staple of our “innocent” escapist entertainments as images of Russians like Khruschev taking off a shoe and beating it against a table were in the 50s. According to Bernard Weintraub in the September 16 New York Times, reporting on the latest deep-dish Industry Wisdom, explosions and hijackers are now out and wholesome family dramas and “escapist comedies” are back in — if one can assume (and I wouldn’t) that they’ve ever been away. Unfortunately, Weintraub identifies Dr. Zhivago and The Sound of Music — the latter set in the Nazi era — as “escapist movies” of the past and The Graduate as an example of the “darker” realities accompanying the war in Vietnam, so what any of this means is anyone’s guess. In other words, more Bush babble, by the bucketful.

What some Americans appear to mean by “collateral damage” is low-value targets hit in other countries, which is business as usual and therefore excusable: maybe the Gulf war and the sanctions against Iraq have already killed about a million people, most of them women and children — the estimate given to me by the American Friends Service Committee a few months ago — but hey, that’s okay, because even if the Gulf war was handled by one of this country’s leading public relations firms, Hill and Knowlton, who were financed in turn by rich Kuwaitis, we know that our intentions in that part of the world are impeccable. I mean, we’re nice guys — honest! — even if we sometimes don’t have much of a clue about what we’re doing. So if we still haven’t hit or even nicked Saddam Hussein — the intended target, whom these low-value Arabs have already had to suffer under for years, and who has meanwhile been enjoying a bonanza of anti-American sentiment thanks to our noble indifference to Iraqi suffering — at least we’ve proven that we mean business. And bombing that pharmaceutical factory in Sudan in 1998, however unfortunate, is still forgivable because — ooops — we thought it was a chemical weapons facility. This proves that we’re good people who are simply fallible — unlike those brilliant, evil, primitive Arabs who actually hit most of their targets last week.

I’m not trying to deny any of the horror of what happened last week. If anything, I’m trying to stress the further horror of some Americans not being able to fathom why some people in the Middle East (and other parts of the world, for that matter) could possibly hate us so much — an innocence that has now become so dangerous that it could wind up doing to this planet what a group of terrorists did to three large buildings last week. Yet the same people who are shocked and enraged by a few Palestinians celebrating last week’s disaster — shown repeatedly on TV like a mantra, to whip us up into a proper fighting mood — might stop and reflect that one could just as easily have found equivalent images of Americans rejoicing over some of the Gulf war hits. (This isn’t a fantasy of mine. Among the more jubilant celebrants were members of my family, as well as some treasured friends and colleagues.) But of course those victims weren’t real, unlike the American victims — or at least the American victims we choose to grieve over. (A few test questions: What about the 80 or so Muslims who were killed in the terrorist attack, apparently not counting the terrorists themselves? Should we base our relative grief about them according to how many were American citizens and how many weren’t? Do American racists lose any sleep over such issues before attacking American mosques? And should any of us give a shit whether or not racists happen to be American citizens? [This one deserves an answer: Yes — if the racists in question insist on it.] If we consider that the number of Muslims in the U.S. roughly equals the population of New York City, that’s a lot of factoring out in every definition of America that contrives to exclude them.) Which leads me to what gives me some cautious hope about the long-range effects of this tragedy — assuming that we allow the planet and ourselves the luxury of having a long range.

***

Part of the shock and pain of the attack was the sudden recognition that this country is, in fact, part of the world. However much that notion may sound like a truism, the working assumption for a good many Americans has been that this country simply is the world, while everything else is something on the order of movies with subtitles, exotic vacations, fancy gourmet meals, bad television, and lots of weird people who want nothing except to be like us and have what we have. The market-driven isolationism that has overtaken this country in recent years might be a swell way of selling products by circumscribing and controlling markets, but it’s a solipsistic luxury we — and the rest of the world — can no longer afford if it expects to survive. To put it even more bluntly, we are the rest of the world, and the rest of the world is us. We’re too implicated in them and they’re too implicated in us — in terms of common experience, common interests, and proximity — for us to go on pretending otherwise. (As for movies with subtitles, I get regular complaints from some local readers for paying too much attention to films they’ve never heard of — meaning films that don’t have multi-million-dollar ad campaigns designed to make them seem like they’re already part of nature. But countries they’ve never heard of seem to fare even worse.)

For me, the pain of discovering details about the individual disasters on September 11 has been a way of discovering, for the first time, a small piece of what it’s meant to be an Iraqi in recent years — during the so-called Gulf war and throughout the continuing sanctions and bombings. (I question the term “war” when an elephant repeatedly stamping its foot on a community of fleas somehow seems closer to the mark.) Endless heaps of rubble, scattered body parts, broken communications, families desperately trying to trace or locate missing parents or children, acts of individual and collective heroism — all the things that our media has steadfastly denied us access to in Iraq it has rubbed our noses into in New York, Washington, and Pennsylvania, now that it’s suddenly happening to “us”. But we have to realize it’s been happening to “us” all along, even if we’ve been forcibly sheltered from it –and from the rest of the world — like children.

Tribalism plays a significant role in this shielding process — which is why I tend to resist the very notion of a benign tribalism, a tribalism without intolerance, as an oxymoron. On a personal level, as the grandson of eastern European Jews, I’ve been taught to regard myself as Jewish in origin but not exactly Middle Eastern. In point of fact I feel like I’m both — which doesn’t necessarily make me Israeli, but makes it easier for me to empathize with some Iranian filmmakers. (Some American Jews prefer to overlook the fact that there are Jews throughout the Middle East.) My point is that we all have many choices to make within our ethnic identities, and denying these choices to others usually also entails shortchanging ourselves. Which is why I can appreciate it when a French person, after the terrorist attacks, said, “We’re all Americans now” — but only if I can imagine that the reverse could also be true if a similar disaster occurred in France. (Why does that currently seem so unlikely?)

For all the grizzliest details of what some Americans are truly seeing now for the first time — facts about horrible things that people have been experiencing for some time across the globe — we have to bear in mind that we’re still not seeing it all. “Interests” have to be looked after. That’s why I estimate I’ve seen the same footage of a few celebrating Palestinians about eight times on American TV — because I presume that American business has nothing to lose by ramming it down our throats. But footage of a Nintendo game approximating, recreating, and perhaps even inspiring the attacks of two planes on the World Trade Center towers is something I’ve seen only once, on Canadian TV — though it’s something I’ll never forget. While showing the game — a point-of-view shot speeding towards the upper floors of one of the towers — the news segment’s announcer persuasively recounted how effective such a game might have been in training those pilots so that they wouldn’t feel they were flying the planes in that direction for the first time.

Maybe it’s misplaced on my part to make the Nintendo people the possible scapegoats of a disaster that can also be blamed in part on the inefficiency of U.S. intelligence and airport security personnel — though I also have to confess that I already find the subsequent increased precautions inconsistent, arbitrary, and more than a little hysterical. Should I complain about the fact that when I took the bus back to Chicago from Toronto — passing through U.S. customs around midnight, only three days after the 11th — none of my bags was checked, including my hand luggage? Not really, because if anything at all was clarified by the terrorist attacks, this is that many of such precautions are ultimately little more than window dressing. If security guards are now bent on looking for plastic knives and box cutters, what can they do if future airborne terrorists don’t carry weapons at all but decide to use karate? And what if they decide to direct their terrorist acts away from air travel and into other pockets of American life?

These are terrible realities to contemplate. But most people just about everywhere else in the world have had to contemplate them long before this incident, and it’s high time we recognize we’re part of that same world. That’s why I’m hoping that the coalitions with other countries the U.S. government is calling for and requires in its anti-terrorism crusade might serve as both a reality check and some form of restraint on the xenophobic impulse to commit absent-minded mayhem that currently fuels most American fantasies of “retaliation”. I’m not saying Americans are in any sense alone in practicing callousness and brutality, though it’s possibly the illusion that they’re alone that’s gotten them into the majority of their messes. It’s the ultimate paradox for a country that owes so much of its genius and energy to its synthesis of other countries — to its fertile mixes of cultures, ethnicities, genders, and desires — that it often pretends to behave collectively like some ornery Marlboro Man roughing it alone. That’s a lie we have to get over, and if we can manage it somehow — it will obviously take some time — this tragedy might show us the way out, joining our fate with that of the remainder of the planet. (One rule-of-thumb indication of when that lie is being reiterated: whenever the events of the 11th are called the worst act of terrorism ever to have occurred in “America,” rather than the world — a distinction that becomes meaningful only because “America” in this case is taken to mean “the world”.)

The day the towers fell and we suddenly got a taste of our own bitter medicine, my memory went back to one night during my junior high days in Florence, Alabama, at some point in the mid-50s, when a school called Burrell Slater burned to the ground. This was back in the Jim Crow days when there were still things called colored schools and white schools in Alabama. Burrell Slater was the main colored school in town, located on a hill in one part of Court Street, the main drag. Nobody seemed to know who or what caused the fire — I still don’t know — but just about everyone I knew, including my friends at the white school, turned up to watch Burrell Slater burn while the fire trucks tried to extinguish the blaze. One of my best friends at the time, whose name was Lannes, was furious because he was convinced that those Nigras musta started the fire themselves. Why? So they could turn up at our school the following day and ask to be admitted.

This, of course, was sheer fantasy on Lannes’s part. The fire was after the 1954 Supreme Court decision calling for the racial integration of American schools, but it was also before the Montgomery bus boycott launched the civil rights movement. Lannes didn’t have a clue about the kids who went to Burrell Slater because he didn’t know any of them, leaving him free to imagine anything and everything about them. He was just like most of us, including George Bush, when it comes to fathoming those cursed A-rabs — most of whom we should be listening to rather than threatening. Maybe if we live long enough, we might all learn something from one another. Maybe we’ll have to. But until we stop compulsively rattling our sabers, I wouldn’t count on it.