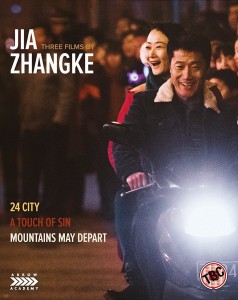

Commissioned by Arrow Films for their dual format boxed set, Jia Zhangke: Three Films, released in the U.K. in early 2018, and reprinted in my collection Cinematic Encounters: Portraits and Polemics (2019). — J.R.

It’s important to acknowledge that part of what makes Jia Zhangke the most exciting and important mainland Chinese filmmaker currently active also makes him one of the most disconcerting and sometimes even bewildering. This has a lot to do with his propensity for viewing fiction and non-fiction, and, even more radically, fantasy and reality, as reverse sides of the same coin, and, in keeping with this complex duality, a talent for bold stylistic shifts not only between successive films but between and within separate sequences. His ambitions are such that even his ‘failures’ are worth more than the successes of many of his colleagues — and, for that matter, what we might describe as a Jia ‘failure’ often means simply a film that we should see again and reconsider.

Confounding us still further in A Touch of Sin (2013), his seventh feature, Jia reverses his previous position of avoiding on-screen violence by delivering it this time by the bucketful. In his earlier features, treatments of violence tended to be reticent or elliptical, so that government executions in Platform (2000) registered as distant gunshots and the tragic and fatal industrial accident of a construction worker in The World wasn’t shown at all. By contrast, A Touch of Sin is already offering us graphic mayhem before all the credits appear, and even the appearance of film’s title is capped by an explosion.

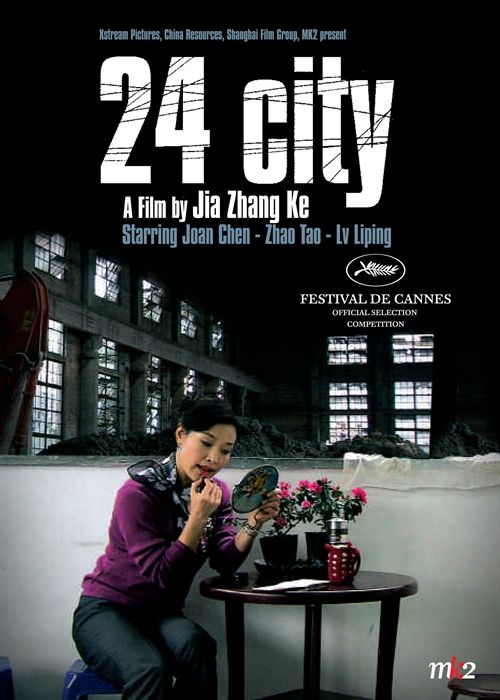

Arguably, most or all of his shifts between reality and fantasy can be traced back to his cinephilia — or, more specifically, to his recognition that movie fantasies shape and alter various aspects of what we commonly regard as reality. This is the precise opposite of Quentin Tarantino’s appropriations of, say, the German occupation of France and American slavery as mere tributaries of his cherished movie fantasies, so that, alarmingly but inevitably, some teenagers today wind up using Inglourious Basterds (2009) and Django Unchained (2012) as historical primers. For Jia, the state of contemporary mainland China is his primary concern and movie fantasies need to be referenced simply in order to examine part of what goes on inside people’s heads. This is why, in his ‘documentary’ 24 City (2008), he can mix real factory workers with four movie actors (all recognizable as such to Chinese audiences) playing other factory workers.

Moreover, starting with The World (2004) — his fourth feature, and the first to be made with government approval — he begins to utilize highly original fantasy interludes. This is a logical step to take in a film about people working in a theme park outside Beijing devoted to fantasy replicas of such world-famous sites as the Eiffel Tower, Lower Manhattan (with the Twin Towers intact), London Bridge, St. Mark’s Square, the Pyramids, the Taj Mahal, and the Leaning Tower of Pisa. These fantasy intervals are always sparked by moments when the film’s alienated characters communicate with one another via text messages on their mobile phones, and they invariably take the form of animation — flights of fancy including the literal flight of one character sailing over the theme park. And quite apart from these cartoon stretches, The World also features a few song-and-dance stage performances that makes the film as a whole resemble a backstage musical, with all the flights of imaginative fancy that this form implies — as well as a somewhat incoherently mystical and distinctly unsatisfying final sequence that creates another disturbance in the film’s realistic narrative.

In Jia’s next feature, Still Life (2006), the fantasies are live-action: a new state monument near the construction site of the Three Gorges Dam suddenly takes off into the sky like a rocket ship (as in an SF movie) and a tightrope artist walks across a high wire stretched between two new skyscrapers in the same vicinity (as in a circus movie). A maker of arthouse films by impulse and instinct, Jia also knows how to instill them with mainstream movie imagery, and indeed, it’s largely his capacity to occupy both realms with equal assurance that makes his position within Chinese film culture so singular.

In A Touch of Sin, the fantasies at play are specifically tied to Chinese culture, Chinese movies in particular. They are also less original, but none the less startling for appearing in this unusual setting — a series of real-life stories gathered from the Internet, most of them familiar to Chinese audiences, offering a survey of contemporary forms of moral and social corruption, and located specifically in all four corners of China and over the four seasons, proceeding backwards in ages from a middle-aged protagonist to increasingly younger characters — all of which imply the sort of ambitions we might associate with an exposé, a manifesto of sorts, and an epic. (Furthermore, Jia periodically recalls some of the places and concerns of his previous features: the first episode is set in his native Shanxi province, the second returns us to the ferry crossing of Still Life, and the fourth is partially set in a sort of fantasy ‘theme park’ brothel that reminds us of The World, and where Jia himself, to suggest his own implication in the fantasy, plays a cameo as the first wealthy customer that we see and hear in this segment.) The film’s English title deliberately recalls King Hu’s A Touch of Zen (1969) and the political implications of his martial arts action stories. (The Chinese title, Tian Zhuding, means ‘ill-fated’, and a further gloss on the English title occurs in the final sequence — at a street performance of the classical opera Yu Tang Chun that formed the basis for King Hu’s first feature.)

What makes these echoes so disconcerting is the way Jia stages shotgun marriages between realistic contemporary details and wuxia conventions, movie-fantasy poses, and the dynamic rhythms of pop-movie violence — all of which threaten to register at times as a reduction (or, for some viewers, elevation) of the characters to familiar icons. On my first viewing of the film — speaking now as a Jia partisan who was relatively unfamiliar with wuxia — it was an alarming reduction, especially in the case of the violence of Zhao Tao’s character in the third episode, and given the rapturous critical response to this film from many of my colleagues, I was uncomfortably reminded of how Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver finally became a hero to everybody by turning into a righteous mass murderer: Was Jia’s depictions of righteous, generic bloodbaths delivered by clichéd killing machines winning him a comparable form of mass approval?

Not really, and certainly not exactly, at least in China. Despite many anticipations of commercial success, the film encountered some belated censorship due to government worries about incitements to violence that delayed its release. In the meantime, the wide circulation of pirated copies brought Jia back to the status of cultish independence that he’d had on his first three features. And a more recent second viewing of A Touch of Sin immediately corrected my initial misimpression. In fact, the adoption by Zhao Tao of familiar wuxia poses after stabbing a sauna customer who’s been slapping her with a wad of bills for not prostituting herself is clearly designed to function as a Brechtian ‘baring of the device’ at the same time that it functions as an absurd fulfillment of the usual genre expectations. That is, it simultaneously invites our applause and makes us feel ashamed and/or embarrassed for applauding. As Jia said to interviewer Nicolas Rapold, ‘In A Touch of Sin the characters are ordinary people. They don’t necessarily have kung fu skills. When they encounter these acts of violence and use their own violence to counteract what was inflicted upon them, they go through a transformation and become like the mystical warriors of the wuxia films. So I’ve treated every instance of violence in the film as a mystical event.” It’s worth adding that Jia’s definition and understanding of violence extend to suicide, diverse kinds of mental cruelty and economic pressure, and, perhaps, above all, to repression and silence — in short, to the toleration of other forms of violence through passivity, fear, or defeated cynicism.

As Jia explained in another interview to Tony Rayns, all four of his main stories — and presumably some of the other stories and forms of corruption or social abuse alluded to only in passing — were found on Weibo, the Chinese equivalent of Twitter, although the first two occurred before Weibo was launched circa 2010, and Jia used the site in those cases for follow-up details:

(1) ‘Black Gold Mountain’: In a mining town in Shanxi, a middle-aged diabetic ex-miner named Dahai (Jiang Wu) attempts to lodge protests against an official who promised but then neglected to pay a percentage of the mine profits to the local populace after the state-run business became privatised, but his efforts are blocked at every turn, even by the local postal service. After being beaten so badly by the entrepreneur’s henchmen that he becomes hospitalised, he loads a rifle and shoots several people in turn, including the corrupt official and a man he sees brutally beating an animal.

(2) ‘Shapingba’: In a village near Chongqing in the southwest Sichuan province, another lone wolf named Zhou San (Wang Baoqiang), a professional killer and thief — whom we have already seen on a motorbike slaughtering several hoods who attempt to rob him in Shanxi province in the precredits sequence — returns home to attend his mother’s 70th birthday celebration and to briefly visit his family. We next see him disguising himself as a streetcleaner, stalking a wealthy couple making a large withdrawal at a bank and then killing them on the street, discarding his disguise, and fleeing.

(3) ‘Nightcomer Sauna’: Zheng Xiaoyu, played by Jia’s wife (and habitual leading lady) Zhao Tao, tries to convince her married lover to leave his wife before visiting her estranged mother and going to work as a sauna receptionist in Yichang (in Hubei province, central China). After being beaten badly by her lover’s wife and the latter’s male friends or relatives, she gets harassed and abused by a sauna customer who insists on having sex with her, and she responds by killing him with a knife.

(4) ‘Oasis of Prosperity’: In Dongguan (in Guandong province, in southern China), a teenage boy named Xiao Hui, working a ten-hour shift on an assembly line at a clothing factory, causes an industrial accident by speaking to a coworker, thus becoming responsible for the coworker’s salary while his wound heals. Further pressured economically by his mother’s demands that he send her more of his wages, he goes to work as a waiter at an expensive brothel, where he falls in love with one of the prostitutes, who explains to him that her work rules out love and that she has a young daughter to support. Further harassed and bullied by some of his fellow tenants at the crowded workers’ tenement where he stays, he leaps from an upper balcony there to his death.

(5) In a final coda, Xiao Wu emerges from prison and moves to Shanxi, where she applies for a job assisting the widow of the corrupt entrepreneur murdered by Dahai. On the street, she watches the performance of a Chinese opera where she hears the recurring line, ‘Do you understand your sin?’

It might be oversimplifying matters to describe this writer-director, born in 1970, as a country boy. But the fact that Jia hails from the small town of Fenyang in Shanxi province clearly plays an important role in all his work. Like William Faulkner and Alexander Dovzhenko, he’s a hick avant-gardist in the very best sense — someone whose outsider and minority status enhances and sustains both his humanity and his art. (In certain respects, his desire to shock and even shame his audience in A Touch of Sin calls to mind Faulkner’s Sanctuary.) Working in long, choreographed takes, and mixing realistic accounts of working-class life with diverse forms of cultural shock and fantasy, he already qualifies as a poetic prophet of the 21st century, and not only for China.