These are expanded Chicago Reader capsules written for a 2003 collection edited by Steven Jay Schneider. I contributed 72 of these in all; here are the third dozen, in alphabetical order. — J.R.

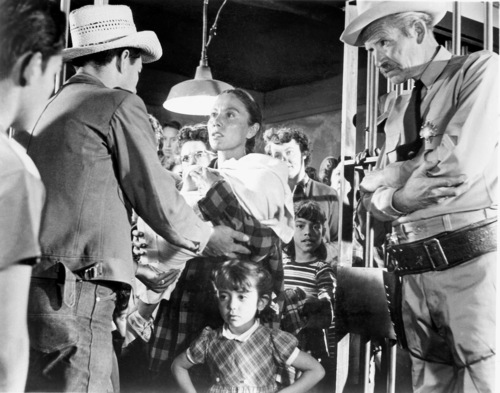

Salt of the Earth

This rarely screened 1954 classic is the only major American independent feature made by communists; a fictional story about the Mexican-American zinc miners in New Mexico then striking against their Anglo management, it was informed by feminist attitudes that are quite uncharacteristic of the period. The film was inspired by the blacklisting of director Herbert Biberman, screenwriter Michael Wilson (A Place in the Sun), producer and former screenwriter Paul Jarrico, and composer Sol Kaplan, among others; as Jarrico later reasoned, since they’d been drummed out of Hollywood for being subversives, they’d commit a “crime to fit the punishment” by making a subversive film. The results are leftist propaganda of a very high order, powerful and intelligent even when the film registers in spots as naive or dated. Basically kept out of American theaters until 1965, it was widely shown and honored in Europe, but it’s never received the recognition it deserves stateside. Regrettably, its best-known critical discussion in the U.S. is in Pauline Kael’s final essay in her first collection — a 1954 broadside in which this film is ridiculed as “propaganda” alongside a forgettable cold war thriller, Night People, that’s skewered as “advertising”. As accurate as Kael is about some of the film’s left-wing clichés, she indiscriminately takes some of her examples from the original script rather than the film itself, and gives no hint of why Salt of the Earth could remain vital half a century later while Night People survives only as a barely watchable curiosity. (JR)

Sans soleil

Chris Marker’s 1982 masterpiece, whose title translates as Sunless (the title given to the film in the United Kingdom), is one of the key nonfiction films of our time — a personal philosophical essay that concentrates mainly on contemporary Tokyo but also includes footage shot in Iceland, Guinea-Bissau, and San Francisco (where the filmmaker tracks down all of the original locations in Hitchcock’s Vertigo —- one of Marker’s key filmic obsessions, as evidenced by his recent CD-Rom Immemory). Difficult to describe and almost impossible to summarize, this poetic journal of a major French filmmaker and video artist (La jetée, Le joli mai, The Last Bolshevik, One Day in the Life of Andrei Arsenevich) radiates in all directions, exploring and reflecting upon many decades of experience all over the world. While Marker’s brilliance as a thinker and filmmaker has largely (and unfairly) been eclipsed by Godard’s, there is conceivably no film in the entire Godard canon that has as much to say about the state of the world, and the wit and beauty of Marker’s highly original form of discourse leave a profound aftertaste. A film about subjectivity, death, photography, social custom, and consciousness itself, Sans soleil registers like a poem one might find in a time capsule. Characterically, it is a film of second thoughts by a photographer, a leftist, and a compulsive globetrotter who remains haunted and transfixed by some of his own images. And significantly, as in his other films and videos, Marker refuses to take a directorial credit. It also seems pertinent that he assigns his own narration to a American woman (Alexandria Stewart) in the English-language version of this film, a woman quotes him only in the third person and past tense —- marking him as a master of indirection. (It’s also indicative of his playful shyness that some of the names in the final credits of this film are anagrams for “Chris Marker”.) (JR)

The Saragossa Manuscript

Jerry Garcia proclaimed this 1965 Polish feature his favorite movie, having seen a pared-down version in San Francisco’s North Beach during the 60s, and a few years back he, Martin Scorsese, and Francis Ford Coppola helped to restore it to its original three-hour length. It’s easy to see how it became a cult film: toward the end of the Spanish Inquisition a Napoleonic military officer (Zbigniew Cybulski — the Polish James Dean, though pudgier than usual here) is morally tested by two seductive Muslim princesses, incestuous sisters from Tunisia, and no less than nine interconnected flashbacks recounted by various characters figure in the labyrinthine plot, its tales within tales imparting some of the flavor of The Arabian Nights and occasional echoes of Kafka (mainly in the eroticism). Krzysztof Penderecki’s score runs the gamut from classical music to flamenco to modernist electronic noodling, and the stark, rocky settings are elegantly filmed in black-and-white ‘Scope. The late Wojciech Has was a good journeyman director, but a film of this kind really calls for someone more obsessive, like Roman Polanski — or at least someone more personally engaged with the material. Adapted by Tadeusz Kwiatkowski from Jan Potocki’s 1813 novel, it’s certainly an intriguing fantasy and a haunting reflection on the processes of storytelling.

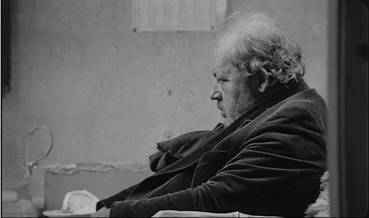

Satantango

How can I do justice to this grungy seven-hour black comedy (1994), which in many ways impressed me more than any other film of the 90s? Adapted by Hungarian director Béla Tarr and Laszlo Krasznahorkai from the latter’s 1985 novel, this is a diabolical piece of sarcasm about the dreams, machinations, and betrayals of a failed farm collective, set during two consecutive rainy fall days (rendered more than once from the perspectives of different characters), and later the same month. The form of the novel was inspired by the steps of the tango — six forward, six backward — an idea reflected by the film’s overlapping time structure, its 12 sections, and its remarkable choreographed long takes and camera movements, which often suggest a despiritualized Tarkovsky with the hothouse intensity of a Cassavetes. Each section ends powerfully with offscreen third-person narration — eloquent, poetic commentary on the characters and their world that comes directly from the novel.

The movie makes us share a lot of time as well as space with its characters, and the overall effect is to give a moral weight as well as a narrative weight to every shot: as detestable as these people are, we’re so fully with them for such extended stretches that we can’t help but feel deeply involved, even implicated in their various maneuvers. Among the extraordinary sequences —- and there are indeed many —- is a riveting tour de force charting for a full hour the chiefly solitary movements of an aging doctor lost in an alcoholic haze, hilariously detailing the amount of exertion required for an overweight man to drink himself into near-oblivion. It’s important to add that the apparent cruelty shown to a cat in another sequence is as expertly faked as the nearly continuous rain; for all the apparent gritty realism, Tarr is a master of artifice.

The story may seem to comment indirectly on the collapse of communism, but it has just as much to say about the subsequent degradations of capitalism; as Tarr has pointed out, the police — and human nature — are the same everywhere. The subject of this brilliantly constructed narrative is nothing less than the world today, and its 431-minute running time is necessary not so much because Tarr has so much to say, but because he wants to say it right.

Schindler’s List

For all its questionable elements, this is one of Steven Spielberg’s best films (1993), and it doesn’t so much forgo the shameless and ruthless manipulations of his earlier work as refine and direct them toward a somewhat nobler purpose. Working from a well-constructed script by Steven Zaillian (Searching for Bobby Fischer) adapting Thomas Keneally’s nonfiction novel — a fascinating account of the Nazi businessman Oskar Schindler, who saved the lives of over 1,100 Polish Jews — Spielberg does an uncommonly good job both of holding our interest over 185 minutes and of showing more of the nuts and bolts of the Holocaust than we usually get from fiction films. One enormous plus is the rich and beautiful black-and-white cinematography by onetime Chicagoan Janusz Kaminski. Spielberg’s capacity to milk the maximal intensity out of the existential terror and pathos conveyed in Keneally’s book–Polish Jews could be killed at any moment by the capriciousness of a labor camp director (Ralph Fiennes) — is complemented and even counterpointed by his capacity to milk the glamour of Nazi high life and absolute power. Significantly, each emotional register is generally accompanied by a different style of cinematography, and much as Liam Neeson’s effective embodiment of Schindler works as our conduit to the Nazis, Ben Kingsley’s subtle performance as his Jewish accountant, right-hand man, and mainly silent conscience provides our conduit to the Polish Jews.

What’s unfortunately missing, and therefore distorted, are many of the more fascinating elements in the real-life story that don’t match Spielberg’s pious, patriarchal scenario —- such as the major role played by Schindler’s wife, Emilie, in saving Jewish lives after he resumed living with her while he was establishing a mock munitions plant in Moravia, or the fact that he continued to betray her with other women. One also wonders how Spielberg might have coped with the bribes that were necessary for many of the Polish Jews to find their way onto Schindler’s list and thus survive. If he had dealt with this sort of material, the film would have probably gained in moral complexity while losing some of its emotional directness. With Caroline Goodall, Jonathan Sagalle, and Embeth Davidtz. (JR)

Se7en

Who would have guessed that a grisly and upsetting serial-killer police procedural (1995, 127 min.) costarring Brad Pitt and Morgan Freeman as detectives, written by a Tower Records cashier (Andrew Kevin Walker), and directed by David Fincher (Alien) would bear a startling resemblance to a serious work of art? One can already tell that this film is on to something special during the opening credits, which formally echo several classic American experimental films and thematically point to the eerie kinship between the serial killer and the police — not to mention the kinship between murder and art making that the movie is equally concerned with. The detectives are trying to solve a series of hideous murders based on the seven deadly sins, and the sheer foulness and decay of the nameless city that surrounds them, which makes those of Taxi Driver and Blade Runner seem almost like children’s theme parks, conjures up a metaphysical mood that isn’t broken even when the film moves to the countryside for its climax.

Admittedly, designer unpleasantness is a hallmark of our era, and this movie may be more concerned with wallowing in it than with illuminating what it means politically. In this respect, it shares some of the duplicity of Taxi Driver -— another film that derives much of its power from this country’s love-hate relationship with fundamentalism, although it should be added that America is hardly alone in experiencing this ambivalence. Se7en is one of the only Hollywood films to have shown widely in post-revolutionary Iran (along with the Godfather trilogy and Dances with Wolves), and even though it likely showed there in censored form, one can’t account for its appeal there simply by noting that its highly skillful cinematographer, Darius Khondji, is Iranian.

The filmmakers stick to their vision with such dedication and persistence that something indelible comes across — something ethically and artistically superior to The Silence of the Lambs that refuses to exploit suffering for fun or entertainment and leaves you wondering about the world we’re living in. Paradoxically, however, one should note that the film originally had a much grimmer ending —- available now as a DVD bonus -— which preview audiences resisted. With Gwyneth Paltrow, Richard Roundtree, John C. McGinley, R. Lee Ermey, and Kevin Spacey.

Seven Brides for Seven Brothers

This is a profoundly sexist and eminently hummable 1954 CinemaScope musical — supposedly set in the great outdoors, but mainly filmed on soundstages — with some terrific athletic Michael Kidd choreography and some better-than-average direction by Stanley Donen. Based on a story by Stephen Vincent Benet, who took his plot from the rape of the Sabine women, it concerns six mangy fur-trapping brothers who go to town to find wives after big brother Howard Keel marries Jane Powell; they wind up following their frontiersmen instincts by kidnapping them, but then have to mope through the winter until their impromptu mates get around to forgiving them in the spring. A fascinating glimpse at the kind of patriarchal rape fantasies that were considered “cute” and good-natured at the time, performed to the catchy music of Johnny Mercer and Gene DePaul. With Russ Tamblyn, Virginia Gibson, and Tommy Rall. Among the most memorable tunes, some of whose titles accurately pinpoint the sexual politics, are “Bless Your Beautiful Hide,” “Sobbin’ Women,” “Goin’ Courtin’,” “I’m a Lonesome Polecat,” and “Spring, Spring, Spring”. (JR)

Shadows

John Cassavetes’s exquisite and poignant first feature (1959), shot in 16-millimeter and subsequently blown up to 35, centers on two brothers and a sister living together in Manhattan; the oldest, a third-rate nightclub singer (Hugh Hurd), is visibly black, while the other two (Ben Carruthers and Lelia Goldoni) are sufficiently light skinned to pass for white. This is the only Cassavetes film made without a script in the usual sense of that term, although Cassavetes scholar Ray Carney has demonstrated at length how the closing title, announcing that the film you have just seen is an “improvisation,” is closer to being a sales pitch than an objective description, and that in fact Cassavetes and Robert Alan Aurthur wrote most of the film, basing their work on a workshop improvisation that was carried out under Cassavetes’ supervision.

Shadows is also the only one of Cassavetes’ films that focuses mainly on young people, with the actors, to increase the feeling of intimacy, using their own first names. Rarely has so much warmth, delicacy, subtlety, and raw feeling emerged so naturally and beautifully from performances in an American film. This movie is contemporaneous with early masterpieces of the French New Wave such as Breathless and The 400 Blows and deserves to be ranked alongside them for the freshness and freedom of its vision; in its portrait of a now-vanished Manhattan during the beat period, it also serves as a poignant time capsule. Tony Ray (the son of director Nicholas Ray), Rupert Crosse, Dennis Sallas, Tom Allen, Davey Jones — all very fine — and cameos by subsequent Cassavetes regular Seymour Cassel and Cassavetes himself round out the cast, and a wonderful jazz score by Charles Mingus featuring alto saxophonist Shafi Hadi plays as essential a role in the film’s emotional pitch as any of them. It’s conceivable that Cassavetes made greater films, but, along with his final masterpiece, Love Streams —- another film focusing on the warmth and empathy between siblings — this is the one I cherish the most. (JR)

Signs & Wonders

Director Jonathan Nossiter and screenwriter James Lasdun, who collaborated on the very promising Sunday (1997), reunite for this ambitious and ambiguous thriller (2000) involving an Americanized businessman in Athens (Stellan Skarsgard) who has twice left his Greek-American wife (Charlotte Rampling at her best) for another woman (Deborah Kara Unger) but still hasn’t given up on their marriage. Shot in digital video as if it were a documentary, the film at separate junctures evokes Nicolas Roeg, Graham Greene, and Richard Lester’s Petulia, even as it takes up multinational corporations, political amnesia, the mixed blessing of American idealism, and some of the monstrous ways love can turn sour. Clearly it bites off more than it can possibly chew, and ultimately it winds up in a pretentious heap. (Some may feel it starts off that way as well.) But Nossiter, an American who grew up in Europe, and Lasdun, an Englishman who currently lives in the U.S., share a sense of cultural displacement that allows them to create something original and provocative. (JR)

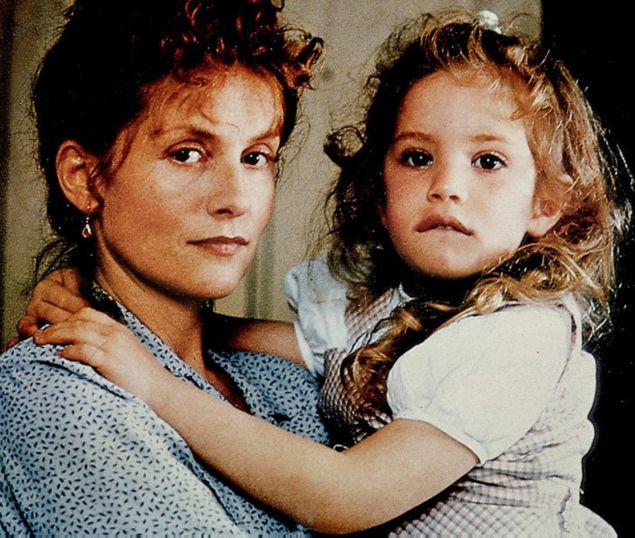

Story of Women

A bit mislabeled — the French title is Une affaire de femmes, which translates better as “Women’s Business” — Claude Chabrol’s accomplished and generally uncharacteristic period film (1988), set in World War II occupied France and loosely adapted from a nonfiction book by lawyer Francis Szpiner, gives a plausible and wholly unsentimental account of a housewife and mother (Isabelle Huppert at her finest) in a small village near Dieppe who becomes an abortionist and is sent to the guillotine for it. Married to a French soldier (François Cluzet) who’s in a POW camp, she doesn’t want to sleep with him after his return; she soon becomes the family breadwinner — a tough survivor who’s also helping other women out.

Cowritten by Chabrol and Colo Tavernier O’Hagan and based on actual events, this film more than makes up for Chabrol’s The Blood of Others, his worst film, adapted from a Simone de Beauvoir novel and set in Paris during the same period of the German occupation —- while looking forward to his excellent 1993 documentary about the same period, The Eye of Vichy. Here his mise en scène and his handling of the period and performances are masterful. (JR)

Strange Days

A movie that gives a new meaning to the word “punchy,” Kathryn Bigelow’s hyperventilating, violent 1995 thriller — entertaining if often over the top — is set in Los Angeles on New Year’s Eve in the year 1999 and has something to do with snuff tapes (with several nods to Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom), racial violence, and police corruption. One feels at times that these matters have been worked into James Cameron and Jay Cocks’s script like fashionable teasers rather than as subjects the filmmakers have much to say about, but they’re certain part of the punchiness. Ralph Fiennes stars as a black marketer who traffics in virtual-reality tapes, and one wonders if surviving fragments of four or five different script drafts are responsible for his changes of personality every half hour or so. I wasn’t in the least bit bored by this movie, and Angela Bassett’s charisma as an action heroine often blows me away, although fans of Bigelow at her best (e.g., Near Dark) may be put off by the acres of calculation, which don’t always fit with the intellectual pretensions. With Juliette Lewis, Tom Sizemore, Michael Wincott, Vincent D’Onofrio, Glenn Plummer, and Richard Edson. (JR)

Tabu

This is the last film of F.W. Murnau, who was probably the greatest of all silent directors. He didn’t live long enough to make sound films, dying in an auto accident a few days after work on the musical score for this masterpiece was completed and a week before the film’s New York premiere. Filmed entirely in the South Seas in 1929 with a nonprofessional cast and gorgeous cinematography by Floyd Crosby, this began as a collaboration with the great documentarist Robert Flaherty, who still rightly shares credit for the story, though clearly the German romanticism of Murnau predominates, above all in the heroic poses of the islanders and the fateful diagonals in the compositions. (As we now know, partly through the detailed research of Murnau specialist Janet Bergstrom, Flaherty was ultimately squeezed out of the project because Murnau, who had all the financial control, wasn’t temperamentally suited to sharing directorial credit, but this unfortunately hasn’t prevented many commentators from continuing to miscredit Flaherty as a codirector.)

Part of Murnau’s greatness was his capacity to encompass studio artifice in such large productions as The Last Laugh, Faust, and Sunrise as well as documentary naturalism in The Burning Earth, Nosferatu, and Tabu — a versatility bridging both his German and American work – and Tabu, shot in natural locations and strictly speaking neither German nor American, still exhibits facets of both of these talents. The simple plot (the two “chapters” of the film are titled “Paradise” and “Paradise Lost”) is an erotic love story involving a young woman who becomes sexually taboo when she is selected by an elder (one of Murnau’s most chilling harbingers of doom) to replace a sacred maiden who has just died; an additional theme is the corrupting power of “civilization” — money in particular — on the innocent hedonism of the islanders. (Murnau himself was in flight from the Hollywood studios when he made the picture, although Paramount wound up releasing it, in 1931.) However dated some of this film’s ethnographic idealism may seem today, the breathtaking beauty and artistry make it indispensable viewing, and the exquisite tragic ending — conceived musically and rhythmically as a gradually decelerating diminuendo — is one of the pinnacles of silent cinema.