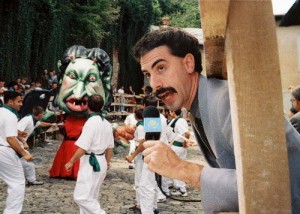

Posted By Jonathan Rosenbaum on 12.23.06 at 06:46 PM

I’d like to ask some of the fans of Borat to explain something to me. I keep reading that this movie is a sly (or not so sly) critique of racism and intolerance based on ignorance, but Sacha Baron Cohen’s apparent semi-ignorant intolerance of the Kazakhs is almost always factored out of the discussion. It’s pretty easy to paint them as a pack of pathetic anti-Semites if you know nothing about them, but isn’t that the kind of glibness Borat is supposedly attacking?

Michael Moore has often been accused of a similar kind of one-upmanship, and with some justification, but why does the even less analytical Cohen get a free ride when he appeals to the same base impulses of the audience? The fact that, as recently revealed, he has the villagers of Kazakhstan speaking Hebrew suggests that maybe he’s enjoying a joke on his more “knowing” spectators as well as his more obvious on-screen targets. But I honestly don’t know what sort of thought — if any — lies behind his use of Kazakhstan or the choice of Hebrew. John Tierney in the New York Times (subscription required) has aptly pointed out that he always could have made Borat a citizen of an invented country instead.

Would any of the people who put the film on their ten-best lists care to comment?

Tags: Borat, Sacha Baron Cohen, Kazakhstan, intolerance

Showing 1-17 of 17