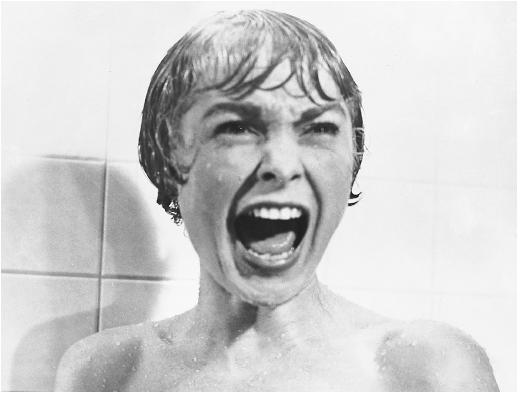

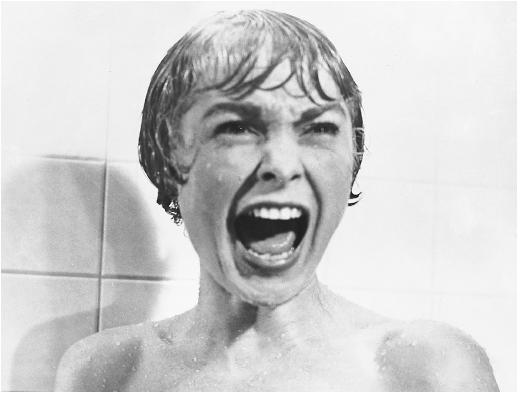

There are few films of the past decade that have irritated me quite as much as Van Sant’s idiotic remake of Psycho, and in some ways I was irritated even more by the rationalizations some cinephiles came up with in their tortured efforts to justify it. I tried my best to behave like a gentleman towards Lisa Alspector, the Reader film reviewer whose capsule sparked my longer review in the December 25, 1998 issue, but I don’t know whether or not I succeeded. — J.R.

Psycho

Rating — Worthless

Directed by Gus Van Sant

Written by Joseph Stefano

With Vince Vaughn, Anne Heche, Julianne Moore, Viggo Mortensen, William H. Macy, Robert Forster, Philip Baker Hall, Ann Haney, and Chad Everett.

Psycho has never been one of my favorite Alfred Hitchcock pictures. The first time I saw it, during its initial release in 1960, I’d already read the Robert Bloch novel it’s based on, a fairly routine horror thriller, so the surprise ending was anything but surprising. I saw the movie back-to-back with Let’s Make Love, which I liked a lot more. Yves Montand spoke English awkwardly, but Marilyn Monroe was irresistible — for practically the only time in her late career, she played a character who was smart and feisty. Read more

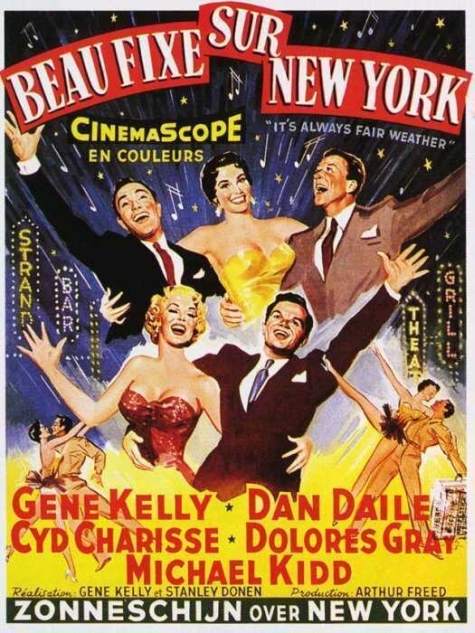

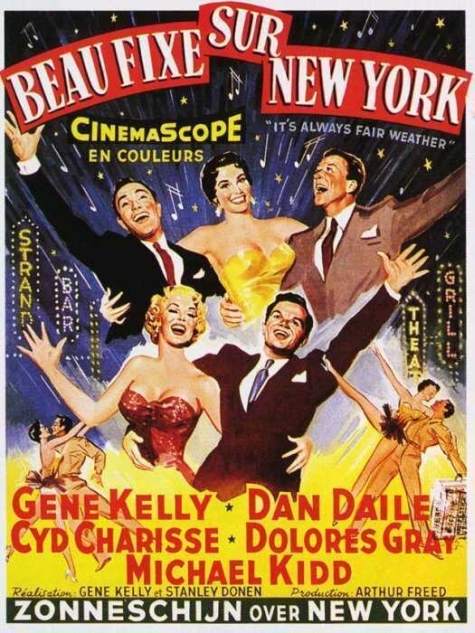

IT’S ALWAYS FAIR WEATHER, directed by Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly, written by Betty Comden and Adolph Green, with Kelly, Cyd Charisse, Dan Dailey, Michael Kidd, and Dolores Gray.

Has there ever been a more deceptive title and ad for a movie than this Belgian poster for the depressive 1955 musical IT’S ALWAYS FAIR WEATHER? Not that the original title or the strained happy ending are exactly apt either. [I resaw this movie yesterday, on my last day at Il Cinema Ritrovato, and might have written about this sooner -– i.e., before I returned to Chicago -– if I’d been able to figure out a way to paste in photos on my laptop.] But in fact it expresses more negative feelings about American culture at mid-century than anything by Frank Tashlin. Tashlin, after all, always seems to love his characters, but what mainly typifies the satirical feelings here about television, advertising, and other forms of corruption are disgust, disillusionment, self-hatred, and anger. It seems characteristic that Kelly and Charisse, the romantic leads, never even get to dance together, and that Dolores Gray’s climactic number, “Thanks a Lot, but No Thanks” (see still), registers as a conscious ripoff of Monroe’s glacially bitter “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend” in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. Read more

From The Soho News (September 15, 1981). -– J.R.

Made in USA

By Jean-Luc Godard

Thalia, September 11 and 12

WHAT could be more timely than a Godard movie that repeatedly returns to the slogan, “The Left, Year Zero”? In point of fact, the beautiful, goofy, and explosive Made in USA was made in France in 1966. But for dispirited moviegoers, having to choose between Blow Out and Prince of the City (or the bossy rival senior critics pushing them) is like having to choose between the United States and the Soviet Union during the 50s (with bland Eisenhower and jocular Khrushchev at the respective helms). All things considered, Made in USA may well be the funniest and punchiest “new” movie around.

It’s the last feature that Godard ever shot with Anna Karina, who was never lovelier and never more made-up to seem at once Japanese and doll-like — in dazzling color and Scope. (Most of the close-ups of her in the movie are the kind of bold compositions you could hang on your wall.) In her off-screen film noir narration, she more or less accurately describes the formal and moral profile of the movie she’s in as ”a film by Walt Disney, but played by Humphrey Bogart — therefore a political film. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 3, 2008). I much prefer this film to Paul Thomas Anderson’s next feature, The Master, an incoherent mess with fewer compensations (despite the heavy breathing from some of my colleagues, who have compared it to Herman Melville); but for my money, neither film holds a candle to Magnolia. — J.R.

Paul Thomas Anderson’s fifth feature, a striking piece of American self-loathing loosely derived from Upton Sinclair’s Oil!, is lively as bombastic period storytelling but limited as allegory. The cynical shallowness of both the characters and the overall conception — American success as an unholy alliance between a turn-of-the-century capitalist (Daniel Day-Lewis) and a faith healer (Paul Dano), both hypocrites — can’t quite sustain the film’s visionary airs, even with good expressionist acting and a percussive score by Radiohead’s Jonny Greenwood. Day-Lewis, borrowing heavily from Walter and John Huston, offers a demonic hero halfway between Thomas Sutpen in Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom! and James Dean’s hate-driven tycoon in Giant (shot on the same location as this movie), but Kevin J. O’Connor in a slimmer part offers a much more interesting and suggestive character. This has loads of swagger, but for stylistic audacity I prefer Anderson’s more scattershot Magnolia. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 6, 2008). — J.R.

No important American filmmaker in recent years has divided audiences more than writer-director Terrence Malick (The Thin Red Line), and his fourth feature in 35 years pushed me for the first time into the skeptics’ corner. The subject matter is partly to blame: after four centuries of Anglo denial about the genocidal conquest of America, I was hoping for something a little more grown-up and educational about John Smith (Colin Farrell) and Pocahontas (the striking Q’Orianka Kilcher). Malick still has an eye for landscapes, but since Badlands (1973) his storytelling skill has atrophied, and he’s now given to transcendental reveries, discontinuous editing, offscreen monologues, and a pie-eyed sense of awe. All these things can be defended, even celebrated, but I couldn’t find my bearings. With Christopher Plummer, David Thewlis, and Christian Bale. PG-13, 135 min. (JR)

Read more

Please go here for all of the listings. — J. R.

Top Blu-ray Releases of 2016

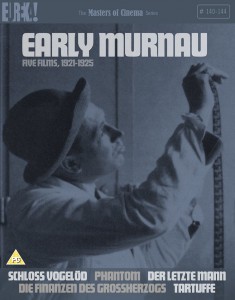

1. Early Murnau (F.W. Murnau, 1921-26), Masters of Cinema, RB, UK)

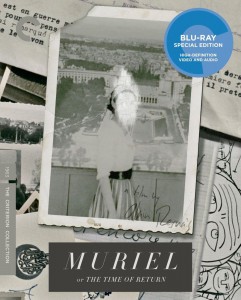

2. Muriel (Alain Resnais, 1963) (Criterion, RA, US)

3. I Want to Live! (Robert Wise, 1958) (Twilight Time, RA, US)

4. Electra, My Love (Miklós Jancsó, 1974) (Second Run Features, RB, UK)

5. The Driller Killer (Abel Ferrara, 1979) (Arrow, RA & RB, US & UK)

6. His Girl Friday (Howard Hawks, 1940) + The Front Page (Lewis Milestone, 1931) (Criterion, RA, US)

7. Napoleon (Abel Gance, 1927) (BFI, RB, UK)

8. The Magic Box: The Films of Shirley Clarke, 1927-1986: Project Shirley, Volume 4 (Milestone Films, RA, US)

9. Son of Saul (Laszlo Nemes, 2015) (Sony Pictures Home Entertainment, RA, US)

10. Dead Pigeon on Beethoven Street (Samuel Fuller, 1973) (Olive Films, RA, US)

Top 10 SD-DVD Releases OF 2016

1. Coffret Nico Papatakis (1963-2004) (Gaumont Vidéo, PAL, France)

2. Les Saisons (Marcel Hanoun, 1968-72) (RE:VOIR, PAL, France)

3. Tricked (Paul Verhoeven, 2012) (Kino Lorber, US)

4. Something Different + A Bagful of Fleas (Vera Chytilová, 1963 & 1962) (Second Run Features, PAL, UK)

5. Read more

An email from Cindy Keefer updating and correcting much of what follows:

Dear Jonathan,

I hope this reaches you.

I just noticed and am very curious why you’ve reposted a 17 year old post about Oskar Fischinger on your blog, reposted on Jan 26, 2018. And those “up to the minute additions” by me at the end, are years old now, definitely no longer up to the minute!! More of the info you have given has changed by this point; one detail is that Center for Visual Music now owns the Fischinger films (gift from the Fischinger Trust). Thus, all those films stills you have online are now (c) Center for Visual Music.

Since then there has been a LOT more Fischinger news, exhibitions and releases – and just now, a new Oskar Fischinger DVD release! Info below.

ALSO – as you may know, I am the curator/archivist for the restoration/reconstruction of Oskar Fischinger: Raumlichtkunst, which has been exhibited in museums worldwide. Though credited incorrectly, you did give some attention to this in artforum in 2012 (my name was excluded as curator, and credit was mistakenly given to a Whitney curator, much to my chagrin). That HD three projector installation continues to be exhibited, most recently in San Francisco, in New Zealand, and at the Whitney for the second time in the recent Dreamlands exhibition.

Read more

This appeared originally in the May-June 1990 issue of Tikkun, and was reprinted in my first collection, Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism, five years later. — J.R.

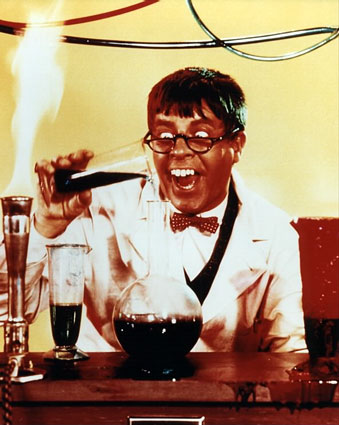

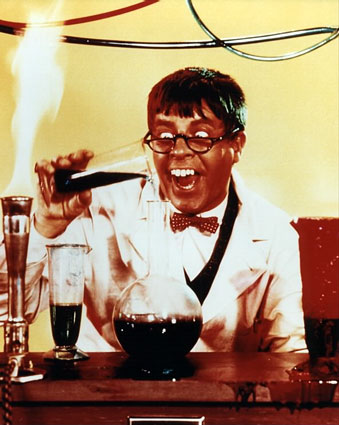

“Why are the French so crazy about Jerry Lewis?” is a recurring question posed by film buffs in the United States, but, sad to say, it is almost invariably asked rhetorically. When Dick Cavett tried it out several years ago on Jean-Luc Godard, one of Lewis’s biggest defenders, it quickly became apparent that Cavett had no interest in hearing an answer, and he immediately changed the subject as soon as Godard began to provide one. Nevertheless it’s a question worth posing seriously, along with a few related ones — even at the risk of courting disbelief and giving offense.

Why are American intellectuals so contemptuous of Jerry Lewis and so crazy about Woody Allen? Apart from such obvious differences as the fact that Allen cites Kierkegaard and Lewis doesn’t, what is it that gives Allen such an exalted cultural status in this country, and Lewis virtually no cultural status at all? (Charlie Chaplin cited Schopenhauer in MONSIEUR VERDOUX, but surely that isn’t the reason why we continue to honor him.) Read more

Jonathan Rosenbaum

This review of was commissioned by its writer-director-producer-editor, Drew Hanks. The Made Man’s trailer can be accessed here: https://youtu.be/rPH9HbveDRk – J.R.

One striking trait shared by the United States and the Catholic Church is a taste for symbolism that overtakes material reality. The same mentality that converts wine into blood can also turn racial differences into graphic abstractions that replace facts so that pinkish brown individuals are called “white” and slightly darker brown individuals can be called “black”.

One of the more eloquent descriptions of this taste for metaphysics over material reality comes from Mary McCarthy, a lapsed Catholic and an American, who argues in her 1947 essay “America the Beautiful: The Humanist in the Bathtub” that “the virtue of American civilization is that it is unmaterialistic”:

“It is true that America produces and consumes more cars, soap, and bathtubs than any other nation, but we live among these objects rather than by them….When an American heiress wants to buy a man, she at once crosses the Atlantic. The only really materialistic people I have ever met have been Europeans….The strongest argument for the unmaterialistic character of American life is the fact that we tolerate conditions that are, from a materialistic point of view, intolerable.” Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 26, 1987). — J.R.

Edgar Neville — an aristocratic Republican filmmaker and writer who was friends with everyone from Lorca and Chaplin to Ortega y Gasset and Lacan — is one of the great undiscovered auteurs of the Spanish cinema. This remarkable turn-of-the-century fantasy, which suggests an eerie encounter between the tales of Borges and the early melodramas of Feuillade and Lang, starts off as a supernatural mystery as the hero (Antonio Casal) is persuaded by a one-eyed ghost to solve the case of his murder. This leads him first to the ghost’s niece (Isabel de Pomes) and eventually to a hidden underground city beneath the old section of Madrid that contains an ancient synagogue and is presided over by hunchbacked counterfeiters. Based on a novel by Emilio Carrere, this hallucinatory fiction ends rather abruptly and never manages to account for all the mysteries it uncovers, but as pure, primal storytelling it is as creepy a spellbinder as one could wish for (1944). (JR)

On November 27, 2017 I received the following email, sent from Spain:

You refer to Edgar Neville in your online review of TOWER OF THE SEVEN HUNCHBACKS as a “Republican”. He was actually one of the other guys, if you know what I mean.

Read more

From Film Comment, September-October 1978. — J.R.

Sound Thinking

#1. The bias against sound thinking is so deeply ingrained that it shapes and invades the most casual parts of our speech. Whenever we ask “What movie did you see?”, or discuss film as a visual medium, or refer to viewers or spectators, we participate in a communal agreement to privilege one aspect of a film text by masking another, identifying the part as a whole. Some might argue that this bias is a carryover from the silent era; yet once we acknowledge that silence is as integral to sound as empty space is to image – not so much a neutral terrain as a variable to be defined and/or filled in relation to an infinite variety of contexts – we can’t really claim that the problem started with the “talkies.” Indeed, we can’t even allude to “talkies” without agreeing to privilege speech over silence, sound effects and music, thereby participating in a related form of suppression.

#2. The point is that none of the terms we use are innocent, and the ones we have for discussing sound still aren’t far removed from Neanderthal grunts. Consider the brutal inadequacy of “sound effects”: it would seem barbaric if we spoke of visual composition in Eisenstein or Renoir as “visual effects,” if only because we perceive composition as a complex of interrelated decisions.

Read more

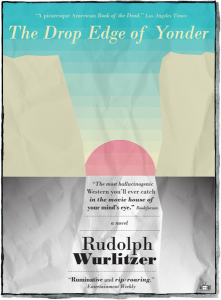

From Written By 3, no. 11, November 1998. — J.R.

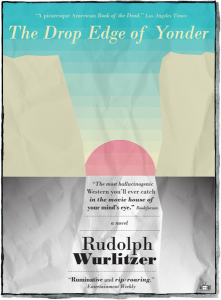

Let me start this off with an update: a plug for Wurlitzer’s most recent novel, a sort of Buddhist Western that grew out of an unrealized script, and a truly haunting page-turner. — J.R.

“What’s your name?” she asked.

“I don’t know,” I said. “I mean, I don’t know how to answer that.”

I was suddenly afraid of losing the anonymity that existed between us, as if once we knew our names the erotic focus we were falling into would dissolve. I curled my lower lip.

“We’re overloaded as it is.”

“Yeah, you’re right,” she said.

— Rudolph Wurlitzer, Quake (1972)

SQUIER We must move southward. Only by expanding can we hope to avoid a civil war and save those in

situtions we hold most precious.

DR. JONES I assume you are including slavery?

SQUIER I certainly am. We must not be sentimental if we wish to preserve that which is most precious to

us. The camera cuts to Ellen, enraged by the conversation. As her eyes dart around the room, she and Walker begin to move their hands in sign language. We see for the first time that Ellen is deaf. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 6, 2006). — J.R.

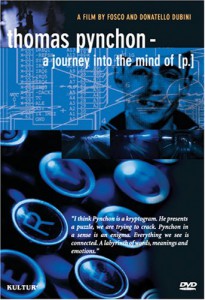

Pynchon freaks can be divided into two categories: those fascinated by his work, who respect his wish to be known through it, and those fascinated by his life, who see his writing as an illustration of his experiences. Aimed at the latter group, this 2001 Swiss documentary by Fosco and Donatello Dubini begins by enlisting a former Pynchon squeeze to show us his LA digs from the early 70s (she’s identified as Bianca from Gravity’s Rainbow, which discounts whatever art he brought to his experiences) and goes mostly downhill from there. Pynchon groupies weigh in while significant critics like Edward Mendelson are omitted, and even as gossip the movie reflects poorly on some of the author’s old friends. But the archival footage does include Lee Harvey Oswald (who may have been in Mexico City at the same time as Pynchon) and a cat freaking out on mescaline. 90 min. (JR) Read more

From the Chicago Reader in July 2000. — J.R.

With the possible exceptions of Killer’s Kiss and A Clockwork Orange all of Stanley Kubrick’s features look better now than when they were first released, and Barry Lyndon, which fared poorly at the box office in 1975, remains his most underrated (though Eyes Wide Shut is already running a close second). This personal, idiosyncratic, and melancholy three-hour adaptation of the Thackeray novel may not be an unqualified artistic success, but it’s still a good deal more substantial and provocative than most critics were willing to admit. Exquisitely shot in natural light (or, in night scenes, candlelight) by John Alcott, it makes frequent use of slow backward zooms that distance us, both historically and emotionally, from its rambling picaresque narrative about an 18th-century Irish upstart (Ryan O’Neal). Despite its ponderous pacing and funereal moods, the film is highly accomplished as a piece of storytelling, and it builds to one of the most suspenseful duels ever staged. It also repays close attention as a complex and fascinating historical meditation, as enigmatic in its way as 2001: A Space Odyssey. The Music Box’s weeklong Kubrick retrospective includes a new print of this and several other films, and it offers an excellent opportunity to reevaluate a filmmaker whose work continues to deepen after his death. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 13, 2001). — J.R.

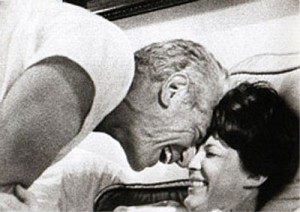

John Cassavetes’s galvanic 1968 drama about one long night in the lives of an estranged well-to-do married couple (John Marley and Lynn Carlin) and their temporary lovers (Gena Rowlands and Seymour Cassel) was the first of his independent features to become a hit, and it’s not hard to see why. It remains one of the only American films to take the middle class seriously, depicting the compulsive, embarrassed laughter of people facing their own sexual longing and some of the emotional devastation brought about by the so-called sexual revolution. (Interestingly, Cassavetes set out to make a trenchant critique of the middle class, but his characteristic empathy for all of his characters makes this a far cry from simple satire.) Shot in 16-millimeter black and white with a good many close-ups, this often takes an unsparing yet compassionate “documentary” look at emotions most movies prefer to gloss over or cover up. Adroitly written and directed, and superbly acted — the leads and Val Avery are all uncommonly good (the astonishing Lynn Carlin was a nonprofessional discovered by Cassavetes, working at the time as Robert Altman’s secretary) — this is one of the most powerful and influential American films of the 60s. Read more