From Written By 3, no. 11, November 1998. — J.R.

Let me start this off with an update: a plug for Wurlitzer’s most recent novel, a sort of Buddhist Western that grew out of an unrealized script, and a truly haunting page-turner. — J.R.

“What’s your name?” she asked.

“I don’t know,” I said. “I mean, I don’t know how to answer that.”

I was suddenly afraid of losing the anonymity that existed between us, as if once we knew our names the erotic focus we were falling into would dissolve. I curled my lower lip.

“We’re overloaded as it is.”

“Yeah, you’re right,” she said.

— Rudolph Wurlitzer, Quake (1972)

SQUIER We must move southward. Only by expanding can we hope to avoid a civil war and save those in

situtions we hold most precious.

DR. JONES I assume you are including slavery?

SQUIER I certainly am. We must not be sentimental if we wish to preserve that which is most precious to

us. The camera cuts to Ellen, enraged by the conversation. As her eyes dart around the room, she and Walker begin to move their hands in sign language. We see for the first time that Ellen is deaf.

Walker notices her agitation. In subtitles we read what she is saying.

ELLEN (subtitles) Screw your institutions. WALKER (translating) Miss Martin says that perhaps not all our institutions are worth saving.

SQUIER (patronizing) Perhaps. But I am sure she would agree that we must save our way of life at any

cost. Otherwise the barbarians will storm the gates and then where will we be? Walker translates what Squier has said into sign language.

ELLEN (subtitles) Go fuck a pig.

WALKER (translating) Miss Martin has a rather different view. She positions herself more on the side of

change, rather than cultural preservation.

— Rudy Wurlitzer, Walker (1987)

One has been hearing lately that the 1960s are making a comeback, but what this actually means is a matter of dispute. Whose 60s is being evoked, and has it ever been away in the first place? If we’re talking about a counter-cultural state of mind, my own 60s has been a constant companion for the past three and a half decades, but for many younger people it remains something of a cryptic, unexplored continent.

Judging by the versions of that decade filtered through most movies and TV, the lingering image of dashed political hopes and bad acid trips has been hard to shake loose, even though this necessarily elides certain political victories (such as the civil rights movement) and a few good acid trips that are less fashionable to remember. Yet the persistence of some legends from the heroic side of that era suggests a solid residue waiting to be noticed — a potent collective vision firmly inscribed in the present that has been obscured by such terms as “new age” and “liberalism”. Let me propose novelist and screenwriter Rudolph Wurlitzer — who started signing his works “Rudy Wurlitzer” in the 80s — as an excellent tour guide to that sensibility.

The story of the talented east coast novelist who is lured out west to write for the movies is almost as old as Hollywood, and it rarely has a happy ending. Although it could be argued that William Faulkner used Hollywood to subsidize his own fiction at least as much as Hollywood used his limited screenwriting skills, a more characteristic tale is that of Jeremy Larner, author of the 60s novel Drive, He Said, whose first screenplay, for The Candidate (1972), won him an Oscar, but who has remained in development purgatory and published no further novels ever since.

Roughly speaking, Wurlitzer’s career to date falls somewhere in between those of Faulkner and Larner. He has continued to publish books as well as write scripts, but where he arguably differs from both–as well as from F. Scott Fitzgerald, Nathanael West, and James Agee — is in the degree to which he has managed to retain his literary persona in many of his best screenplays. Unfortunately, most of these scripts remain to be filmed, though even if one concentrates on some of those that have made it to the screen — especially Two-Lane Blacktop (1971) and Candy Mountain (1987), but also Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973) and Walker (1987) — the continuity with his novels is unmistakable. (In other cases — ranging from his polish of Jim McBride and Lorenzo Mans’ Glen and Randa to his uncredited final draft of Coming Home to his work with Volker Schlondorff on Voyager — it’s either fitful or indiscernible.)

It would diminish Wurlitzer’s considerable originality as a novelist to call him a translator of Samuel Beckett (especially the trilogy of Molloy, Malone Dies, and The Unnameable) into precise American equivalents and home-grown idioms, but that represents at least part of the achievement of his first two novels, Nog (1969) and Flats (1970). In fact, this “translation” is so seamless and so authentically American that it goes well beyond mere recreation. Perhaps one could say that Wurlitzer has applied some of the lessons of Beckett to the meaning of his own experience and created something new out of the encounter, including a use value that never would have occurred to his master.

If loss of history and loss of identity are the preconditions of the shifting Beckett hero (Molloy, Malone, the unnameable), the central figures of Nog and Flats, both minimalist constructs at the outset, gradually take on histories and identities, though the extent to which these are adopted or invented is deliberately left ambiguous. Thus the drifting narrator of Nog is not the eccentric Finnish traveler of that name whom he once met, even if “Nog” becomes his adopted moniker whenever he has to explain who he is to other people. And the various tramps seated around an open fire in the even more minimalist Flats — all of them named after American cities, but so mutable in their identities that they all collapse into one another — add up at most to a single individual. The American ethos behind this process — you are what you do and how you seem, not where you come from and where you go — is one version of the western cowboy myth writ large, and in one way or another, all of Wurlitzer’s best work is replenished by it.

According to Richard Poirier in The Performing Self (1971), it is a process that gave voice to a mainly voiceless counterculture. As he put it, Nog “makes the first ser-ious effort since [Thomas] Pynchon to create a style that renders states of being in which separate identities can barely be located, and, when they are, seem merely accidental. Identities fuse and separate without intention and without feeling, as if persons had the consistency of air….For Wurlitzer to have created a stylistic approximation of these conditions is an accomplishment of some historic consequence, showing that our language can manage to reach into those areas of contemporary life where, among its young inhabitants, there is mostly silence.”

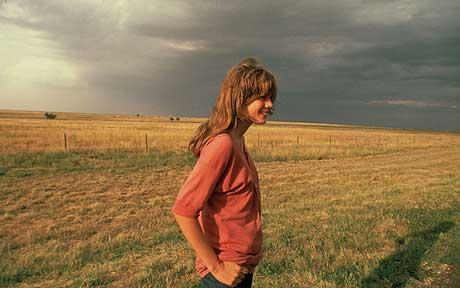

Though it’s hard to imagine a project more inimical to mainstream Hollywood, director Monte Hellman hired Wurlitzer to script Two-Lane Blacktop on the strength of Nog, and his screenplay received the singular honor of being printed in its entirety in Esquire prior to the picture’s 1971 release, where it was heralded on the cover as “the movie of the year”. That the film failed commercially after this fanfare is hardly surprising, yet it survives as one of the key road movies of the era. Chronicling a coast-to-coast race between strangers identified only as The Driver and The Mechanic in one car (musicians James Taylor and Dennis Wilson), G.T.O. (Warren Oates) in the other, the latter of whom immediately assumes a different past and identity with every hitchhiker he picks up, the movie registers as an existential comedy with tragic undertones about going nowhere. Although most of the country gets crossed and many other characters drift through the plot, the process of continuous motion eventually overtakes any sense of destination, and not long after the race gets abandoned, the plot ends metaphysically with the film itself burning up inside the projector.

In a comparable contrary spirit, Wurlitzer recently described to me a script he wants to write for an action film in which the action gets progressively slower. A practicing Buddhist for the better part of 25 years — and one who sharply criticizes his own work on Bernardo Bertolucci’s Little Buddha for its self- consciousness in his 1994 memoir Hard Travel to Sacred Places — he has wrestled throughout his screenwriting career with the challenge of reconciling the rewards of meditation with the forward motion of film narrative, and much of his best screenwriting grows out of this conundrum. It also relates to a desire to broaden the thrust of his writing. He once wrote to literary critic David Seed that he initially turned to screenwriting “for relief and therapy as my prose was so much on the edge of being solipsistic, as well as introverted. I needed, or so I thought then, to be more out in the world, even if it meant being battered by a relentlessly profane marketplace.” A few years later, he wrote that “the first axiom of the screenwriter…is to sublimate language to image.” In keeping with this axiom, apart from the loquacious G.T.O, Two-Lane Blacktop moves along with a minimum of dialogue.

No less ambitious was Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, also written for Hellman, but the ambitions in this case collided with those of Sam Peckinpah, who later inherited the project and ordered changes. In Wurlitzer’s version, the title characters never meet until the last scene, when the former kills the latter; Peckinpah made them old friends from the outset and added a prologue flashing forward to Garrett’s own death 18 years later. The results are an unstable mix of Wurlitzer’s dry, flavorsome dialogue — always

one of his strongest suits–and Peckinpah’s more high-flown and elegaic sentiments, complicated still further by various location disasters and studio tampering. As partial compensation, Wurlitzer eventually published a draft of his own version of the script as a mass market paperback, introduced by an account of the project’s checkered past that pointedly neglects to mention Peckinpah’s name once.

Wurlitzer’s best western script, however, remains unfilmed — a powerful turn-of-the-century tale about former mountain trapper Boone Pike breaking out of Northwest Territorial Prison with a bullet in his heart and fleeing cross-country so that he can die with what remains of his family. Mountain of the Heart — like Wurlitzer’s more recent (and perhaps second-best) western script Gold Fever, set in the mid-19th century — proceeds on an epic scale, in striking contrast to the minimalism of his early work, but it represents an evolution rather than a negation of what went before because the same concentration of language and incident is evident.

These and other scripts reveal retroactively how much a precoccupation with history pervades all of Wurlitzer’s work — including all four of his novels, Two-Lane Blacktop, Candy Mountain, and Just To Be Together (a recent and unrealized script coauthored by Michelangelo Antonioni that revises their previous collaborative screenplay, Two Telegrams), all of which have contemporary settings. The minimalist histories of Wurlitzer’s characters in Nog, Flats and Two-Lane Blacktop represent not rejections of history but searches for what is essential — that is, useful — about the past in relation to the present. This is also why the post-apocalyptic Los Angeles setting of his third novel, Quake (1972), charting social disintegration after an earthquake, and the filmmaking milieu of his fourth, Slow Fade (1984) — part of which clearly derives from his on-location experiences and skirmishes with Peckinpah — vividly reflect their respective decades. (As Gary Indiana noted in the Village Voice a few years ago, all of Wurlitzer’s books can be read as “socio-logical artifacts” and period pieces.) It furthermore helps to explain why Wurlitzer’s current novel-in-progress is set in the 19th century, and why his recent screenplay Shinobi — a remarkable Ninja fantasy inspired in part by early films of Akira Kurosawa — is mainly set in the year 1600. Yet another recent unrealized script, Dark Angel, adapting J.F. Federspiel’s novel The Ballad of Typhoid Mary, is set during the same period as Mountain of the Heart, albeit on the other side of the United States — New York City at the end of the 19th century.

Walker is a satirical fantasy about the real-life exploits of William Walker, the American southerner and onetime abolitionist who ruled Nicaragua from 1855 to 1857 and altered its constitution to reinstate slavery. Written for eclectic cult director Alex Cox and boldly filmed on location (though far south of the war being waged then against the Contras), it’s the most overtly political of Wurlitzer’s scripts, and sufficiently radical to have evoked the scorn of most mainstream critics, though the wit behind its anger — including several deliberate anachronisms that make its contemporary relevance unmistakable — continue to make it suggestive and potent.

Significantly, Wurlitzer largely views Walker’s arrogance in terms of rhetoric and language, such as the fact that the offscreen narration of Walker, played by Ed Harris, eerily alternates between first and third person (a ruse inspired by Walker’s book The War in Nicaragua). This connects up with the use of sign language and subtitles in relation to Walker’s deaf-mute fiancee Ellen Martin, cited at the beginning of this article, and is equally apparent in a dialogue with Cox that was published at the time of the film’s release, in which Wurlitzer said, “We don’t have the right to interpret Nicaragua for Nicaraguans….It’s not our business with left governments, right governments, any governments, you know? And we must defend our right to be innocent that way. Our fight not to be sophisticated. We must defend our right not to join that language, to be innocent and to refuse that dialogue.”

Considering how many of Wurlizer’s projects are road movies, his most characteristic script may be the one he wound up codirecting with Robert Frank, Candy Mountain. (1987). The hapless hero, a wanabee musician named Julius Book (Kevin O’Connor), works his way north via various barter exchanges from New York into the remote Canadian wilderness, in search of a legendary guitar maker named Elmore Silk, subsidized by music entrepeneurs who want Silk to resume his craft. Bearing an audiocassette carrying messages from Silk’s former associates, Book encounters Silk’s discarded friends, lovers, and relatives, who add their own messages to the tape, along with Book’s own ruminations and bulletins of his progress. When Silk eventually plays the tape back, the parallel portraits of his gradual retreat into the wilderness and the reasons for that retreat–the culture he has fled — are equally evident. If it’s a movement that recalls the shape of Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness,” the Silk at the end of the rainbow is the opposite of Conrad’s Kurtz (a figure who has more in common with Walker). Signing an agreement with Japanese investors to turn over a dozen of his guitars, destroy the rest, and make no more, Silk cheerfly abdicates the patriarchal power that Book and the other characters have invested him with and donates most of his life’s work to a bonfire.

Given all the autobiographical resonances in Wurlitzer’s script, it’s clearly one of his most personal works.Born in Cincinnati in 1937, he comes from the famous family of musicians and instrument makers that gave us the Wurlitzer organ, and his own periodic flights into the wilderness from New York and Los Angeles — his principal bases nowadays are Nova Scotia and Hudson, New York — describe the retreats and drifts of his fiction and screenwriting. Most important of all, the deliberate relinquishment of power, a key aim of 60s counterculture, represents the closest thing in his work to utopia.