From The Soho News (September 15, 1981). -– J.R.

Made in USA

By Jean-Luc Godard

Thalia, September 11 and 12

WHAT could be more timely than a Godard movie that repeatedly returns to the slogan, “The Left, Year Zero”? In point of fact, the beautiful, goofy, and explosive Made in USA was made in France in 1966. But for dispirited moviegoers, having to choose between Blow Out and Prince of the City (or the bossy rival senior critics pushing them) is like having to choose between the United States and the Soviet Union during the 50s (with bland Eisenhower and jocular Khrushchev at the respective helms). All things considered, Made in USA may well be the funniest and punchiest “new” movie around.

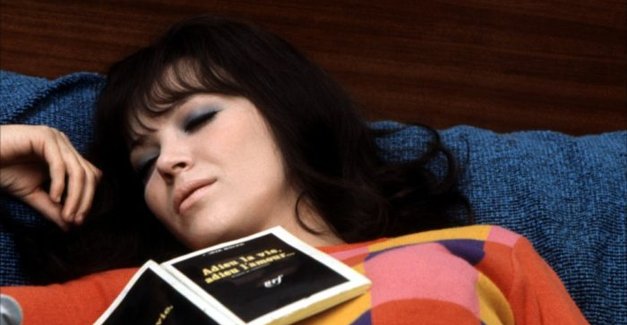

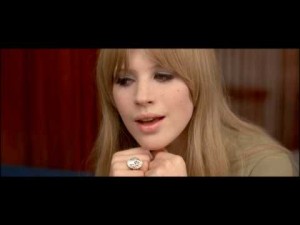

It’s the last feature that Godard ever shot with Anna Karina, who was never lovelier and never more made-up to seem at once Japanese and doll-like — in dazzling color and Scope. (Most of the close-ups of her in the movie are the kind of bold compositions you could hang on your wall.) In her off-screen film noir narration, she more or less accurately describes the formal and moral profile of the movie she’s in as ”a film by Walt Disney, but played by Humphrey Bogart — therefore a political film. ” Even in a wobbly 16mm print, the New York theatrical premiere of Godard’s ultimate statement about his love/hatred for the aesthetics/politics of American movies/life is an event to be savored and celebrated, at the very least, not ignored.

For starters, the movie’s dedicated “to Nick and Samuel” (Ray and Fuller), “who taught me respect for image and sound”. Students of American cinema in the 50s who are looking for the best critical treatment of the subject should head for neither bookstore nor library, but straight for this movie. Just as Alphaville conceivably has as much to say about German expressionist cinema as either Siegfried Kracauer or Lotte Eisner, Made in USA is provocative, first-rate film criticism, cunningly composed in the language of the medium, about violent Hollywood iconography of the 50s, in both the crime thriller and the animated cartoon.

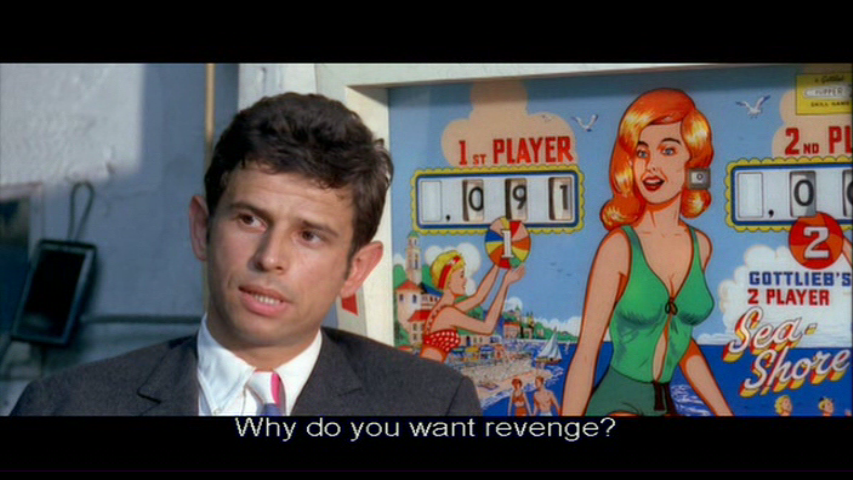

As John Kriedl helpfully points out in his recent study of Godard published by Twayne, an important aspect of this critique is “the almost continuous use of ‘the Hollywood shot’ or medium shot cut off at the knees,” a shot significantly known in French as the plan américain. Godard often freezes this shot into planes of brightly colored stripes and overlapping diagonals, angles as sharply pointed as Dick Tracy’s chin, with blocks of glacial primary colors and rasping, staccato and percussive sounds that bring alternative American models of consciousness, like pinball machines and comic strips, into the act.

Then there’s the picaresque detective investigation plot – Karina as Paula Nelson in a Bogart trench coat — filched from movies like The Big Sleep and Kiss Me Deadly, and characters with names like Inspector Aldrich, David Goodis, Donald Siegel, Richard Widmark, Mark Dixon and Dr. Korvo (the latter two characters in minor Preminger thrillers, Where the Sidewalk Ends and Whirlpool), Robert McNamara and Richard Nixon. This in turn is politically contextualized by impenetrable. paranoid events like the first Kennedy assassination and The Ben Barka affair, and set in an anonymous French suburb confusingly called Atlantic City. Summoned there by a telegram from her lover Richard (whose last name is repeatedly smothered by ringing phones, jet planes, and car horns), she soon enters an absurdist labyrinth of entanglements with cops and gangsters.

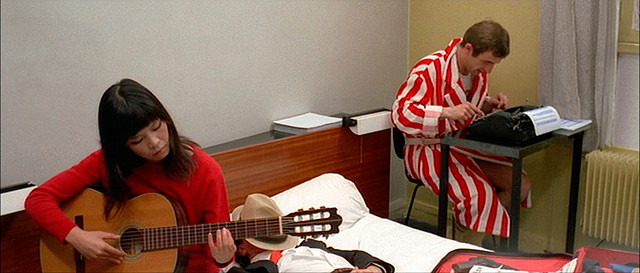

There are many links to earlier New Wave films: Rivette’s Paris Belongs To Us, Godard’s Le petit soldat and Pierrot le fou, and Truffaut’s Shoot the Piano Player. Jean-Pierre Léaud walks around with a forlorn expression, a pocket pinball game, and a “Kiss me, I’m Italian” button, while in place of a Jean-Paul Belmondo we get Yves Alfonso in a striped bathrobe, who sports a similarly shaped nose. Made almost simultaneously with Two or Three Things I Know About Her, Godard’s major critical statement about documentary, Made in USA echoes its companion piece in a few structural particulars: a plan américain of the heroine lighting a cigarette on the street in front of peeling posters; a long, sagging, and monotonous dialogue sequence set in a café bar. (Ever since Sartre wrote about the café waiter playing at being a café waiter in Being and Nothingness, a surprising amount of existentialism and related French thought seems to have been formulated in relation to café culture.)

“Mystery and fascination of this American cinema,” Godard wrote around the same time he was completing Made in USA, after reseeding yet another minor Preminger, Fallen Angel. “How can I hate McNamara and adore Take the High Ground, hate the John Wayne who upholds Goldwater, and love him tenderly when he abruptly takes Natalie Wood into his arms in the next-to-last reel of The Searchers?”

Reformulating this dilemma again and again informal terms – always critically, and never reverentially or sycophantically in the Wenders or Bogdanovich manner, Godard turns Made in USA into a collage film composed almost exclusively of colliding citations and incidental vaudeville: Marianne Faithful crooning “It is the evening of the day” and a Japanese woman named Doris Mizoguchi singing in a shower; Laszlo Szabo imitating Sylvester the Cat and Tweetie Pie. Daisy Kenyon, Ruby Gentry, and director Edward Ludwig are all paged over the p.a. system in a health club out of Frank Tashlin, and abstract expressionist eruptions of red paint and other simulated gore flash by in BandAid-shaped compositions. My favorite sequence -– in which fragmented, disembodied movie-theater posters and cutouts seem to float around a garage, while Szabo and Karina discuss mise en scène as a political maneuver –- has all the electric thrill of a Rauschenberg painting in motion.