On Criterion’s very attractive DVD release of Alex Cox’s Walker, there’s a pretty funny bonus feature consisting of Cox reading aloud from the almost exclusively negative and dismissive U.S. reviews that the film received when it came out in 1987. I’m sorry that he doesn’t read from — and apparently wasn’t aware of — my near-rave in the Reader, written during my first year at the paper, so I’m reprinting it here.

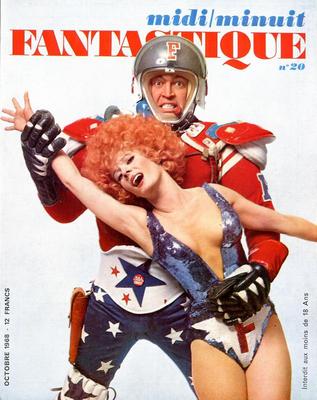

For me, this ties in with the surprisingly warm and appreciative welcome accorded to William Klein’s Mr. Freedom (1967) when I showed it in my 60s world cinema course a few years ago. It even sold out every ticket at the Gene Siskel Film Center’s larger auditorium, which I doubt would have happened even in the 60s. I guess it takes a George W. Bush or a Donald Trump to make 60s radicalism both fashionable and available again.

(For more on William Klein, go here.)

Walker is scripted by the novelist Rudy Wurlitzer — who also wrote Two-Lane Blacktop (also recently released on an excellent Criterion DVD set) and has recently published his first novel in almost a quarter of a century, The Drop Dead of Yonder, a sort of Buddhist Western which I strongly recommend. Read more

I’d completely forgotten about my having written this piece until I came across it recently here, complete with the photo of me (apparently in late 1999) delivering this paper at a panel discussion in Chicago. Apart from correcting a few typos and adding some other photos, I’ve reproduced it here more or less as I found it. (Afterword, April 2, 2015: I’ve done a light edit on this.) — J.R.

It’s tempting but dangerous to approach artists from exotic cultures in terms of more familiar reference points such as comparing Zhang Yimou’s Ju Dou to The Postman Always Rings Twice or reading Souleymane Cissé’s Brightness as if it were an African Star Wars, as some American and English critics have done. Yet to describe the styles and visions of the two major Iranian filmmakers of the Eighties and Nineties, Abbas Kiarostami and Mohsen Makhmalbaf, I’ve been exploring comparisons to Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoevsky — a project obviously fraught with booby traps, but one that none the less clarifies some of the important differences between these two major figures.

A key difference which has only an oblique relevance to my comparison is that Makhmalbaf has been the most popular and respected filmmaker in Iran in recent years, despite his many run-ins with state censors, while Kiarostami is a hero principally elsewhere. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (November 19, 1999). — J.R.

Winner of the 1998 Palme d’Or at Cannes, this rambling but beautiful feature by Theo Angelopoulos may seem like an anthology of 60s and 70s European art cinema: family nostalgia from Bergman and seaside frolics from Fellini; long, mesmerizing choreographed takes and camera movements from Jancso and Tarkovsky; haunting expressionist moods and visions from Antonioni. Yet it’s so stirring and flavorsome — far richer emotionally and poetically than Woody Allen’s derivations — that I was moved and captivated throughout its 132 minutes. Bruno Ganz is commanding as a Greek writer who’s recently learned that he’s terminally ill; the part was conceived for the late Marcello Mastroianni, yet Ganz seems perfect for it (though he’s dubbed by a Greek actor, as Mastroianni undoubtedly would have been). Brooding over the loss of his seaside retreat and family home in Thessaloniki, the hero meets an eight-year-old illegal alien from Albania (Achilleas Skevis) and spends the day crisscrossing the past and visiting his familiar haunts, sometimes in the flesh and sometimes in his imagination, and Angelopoulos is masterful in orchestrating these lyrical and complex encounters. With Isabelle Renauld. Music Box, Friday through Thursday, November 19 through 25. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 1, 1999). — J.R.

Pushing 100, Portuguese writer-director Manoel de Oliveira is our oldest living film master, which makes it all the more astonishing that he’s averaged one feature a year since the ’80s. His finest work is bound to literature and theater, and this eccentric triptych (1998) is one of its absolute peaks. It consists of a one-act play (Prista Monteiro’s The Immortals) and a story by Antonio Patricio about four people who attend it, one of whom recounts the third story, Agustina Bessa-Luis’s The Mother of the River. The theme of this exquisite masterpiece, linking all three parts, is existential identity, played out in each case by two characters — father and son, playboy and prostitute, young village woman and ancient witch. The witch is played by Irene Papas, and de Oliveira can be seen dancing with his wife in the middle episode. In Portuguese with subtitles. 114 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (December 1, 2000). — J.R.

Requiem for a Dream

**

Directed by Darren Aronofsky

Written by Hubert Selby Jr. and Aronofsky

With Ellen Burstyn, Jared Leto, Jennifer Connelly, Marlon Wayans, Christopher McDonald, and Louise Lasser.

Darren Aronofsky’s first feature, Pi (1998), had more style than substance — or perhaps it’s just that the only thing I now remember with much clarity is its razzle-dazzle style. The black-and-white cinematography and the jazzy editing were pretty attractive in a disposable sort of way, though critic Bill Boisvert had a point when he suggested in these pages that the attitude of this metaphysical thriller was “profoundly anti-intellectual,” rightly adding that this was “true of most indie genius films.” (He may have been more right than he realized. His second example was the 1997 Good Will Hunting, directed by Gus Van Sant, who’s been offering us nothing but anti-intellectual holiday releases about geniuses ever since — with Alfred Hitchcock rather than Norman Bates as the prodigy in the 1998 Psycho remake and Robert Brown taking the equivalent role in Finding Forrester, which opens on Christmas day.)

When I belatedly caught up with Aronofsky’s second feature, Requiem for a Dream, it was with the hope of seeing something more than just fancy style. Read more

From the March 1, 2000 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

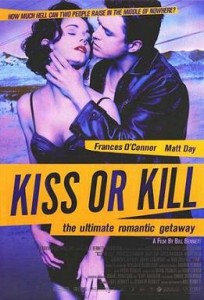

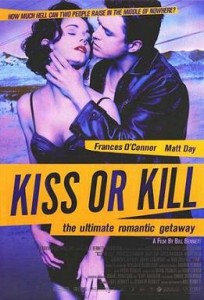

Who needs another killer couple fleeing cross-country with cops in hot pursuit? Yet thanks to this 1998 Australian thriller’s aggressive and unnerving formal approach — jump cuts that hurtle us through the story like a needle skipping across a record and an inventive camera style that defamiliarizes characters as well as settings — the characters’ paranoia is translated into the slithery uncertainty of our own perceptions: this is the most interesting reworking of noir materials I’ve seen since After Dark, My Sweet and The Underneath. The creepy alienation of the lead couple (Frances O’Connor and Matt Day) from their victims and the world in general is eventually replicated in their own relationship, and variations on the same kind of mistrust crop up between the cops pursuing them and in just about every other cockeyed existential encounter in the film. Apart from some juicy character acting and striking uses of landscape, what makes this genre exercise by veteran director Bill Bennett special is the metaphysical climate produced by the style, transforming suspense into genuine dread. The outback is an eyeful too. 95 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

This was originally a lecture given at a conference on Godard held in Cerisy, France on August 20, 1998. It subsequently appeared in a printed form somewhat closer to that found below, in Screen magazine (vol 40, no. 3), in Autumn 1999, as part of a Godard dossier assembled by the estimable Michael Witt. But, if memory serves, it took about a year of correspondence and wrangling before anyone on the magazine’s staff agreed to send me any copy of the issue. (Note: for a more general essay and interview with Godard about Histoire(s) du cinéma, go here.) —J.R.

Le Vrai Coupable: Two Kinds of Criticism in Godard’s Work

Jonathan Rosenbaum

Since the outset of his career, Godard has been interested in two kinds of criticism — film criticism and social criticism — and these two interests are apparent in practically everything he does and says as an artist. The first two critical texts that he published — in the second and third issues of Gazette du cinéma in 1950 — are entitled “Joseph Mankiewicz” and “Pour un cinéma politique”, and his first two features, A bout de souffle and Le petit soldat, made about a decade later, reflect the same dichotomy. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 6, 1998). — J.R.

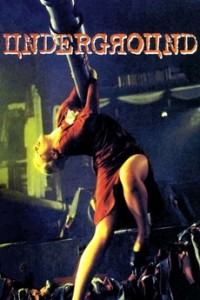

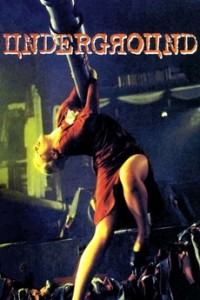

Though slightly trimmed by director-writer Emir Kusturica for American consumption, this riotous 167-minute satirical and farcical allegory about the former Yugoslavia from World War II to the postcommunist present is still marvelously excessive. The outrageous plot involves a couple of anti-Nazi arms dealers and gold traffickers who gain a reputation as communist heroes. One of them (Miki Manojlovic) installs a group of refugees in his grandfather’s cellar, and on the pretext that the war is still raging upstairs he gets them to manufacture arms and other black-market items until the 60s, meanwhile seducing the actress (Mirjana Jokovic) that his best friend (Lazar Ristovski) hoped to marry. Loosely based on a play by cowriter Dusan Kovacevic, this sarcastic, carnivalesque epic won the 1995 Palme d’Or at Cannes and has been at the center of a furious controversy ever since for what’s been called its pro-Serbian stance. (Kusturica himself is a Bosnian Muslim.) However one chooses to take its jaundiced view of history, it’s probably the best film to date by the talented Kusturica (Time of the Gypsies, Arizona Dream), a triumph of mise en scene mated to a comic vision that keeps topping its own hyperbole. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (Mar 1, 1998). — J.R.

After his first two features in the early 60s (The Love Game, The Five-Day Lover), Philippe de Broca, a former assistant to Francois Truffaut and Claude Chabrol, was taken by some to be a member of the French New Wave — an impression that was quickly undermined by the glossy commercial fare that followed, including this enjoyable 1964 thriller romp with Jean-Paul Belmondo and Francoise Dorleac. If memory serves, this is swell light entertainment — there’s a nice score by Georges Delerue, and the original screenplay was nominated for an Oscar — designed to autodestruct as soon as you see it. (JR)

Read more

From Chicago Reader (August 1, 1998). — J.R.

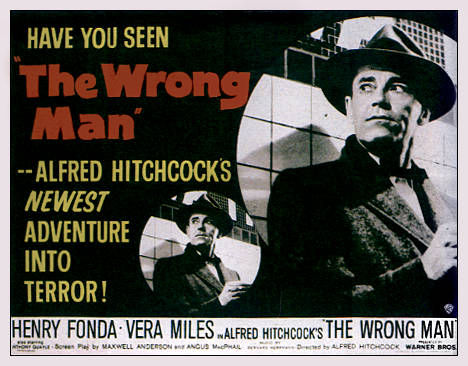

Federico Fellini’s restored 1957 masterpiece, starring his wife, Giulietta Masina. Though the additional scene — an incident involving a man who distributes food and clothing to the homeless — may have little consequence in terms of the overall plot, it changes one’s thematic and spiritual sense of the whole film. The story basically consists of five lengthy episodes in the life and career of a prostitute who repeatedly becomes disillusioned but keeps finding the resources to believe in romantic love just the same. Masina’s exaggerated grimaces and clownlike features, which hark back to the tradition of silent comics, are undoubtedly mannerist, but part of Fellini’s mastery is to make them necessary correlatives to his own vision of innocence. Too melodramatic and fanciful in turn to qualify as neorealism in the usual sense, despite the gritty Roman street slang contributed by Pier Paolo Pasolini, this gains immeasurably, like many other Fellini films, from Nino Rota’s wistful music. In Italian with subtitles. 117 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

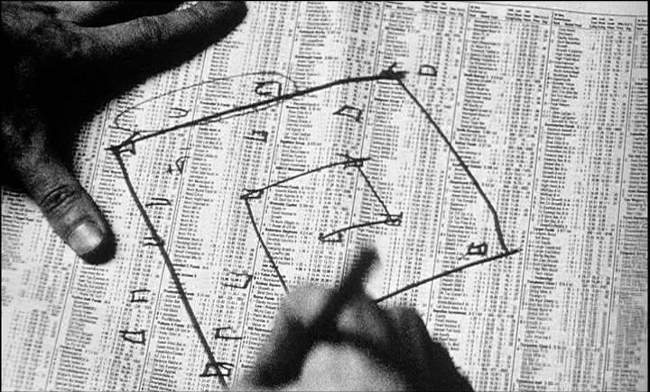

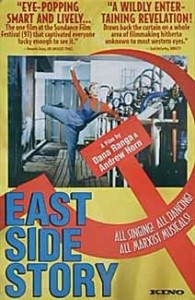

East Side Story, a recent documentary about communist musicals, assumes that communist-bloc directors were just itching to make Hollywood extravaganzas and invariably wound up looking strained, square, and ill equipped. But Red Psalm (1971), Miklos Jancso’s dazzling, open-air revolutionary pageant, is a highly sensual communist musical that employs occasional nudity as lyrically as the singing, dancing, and nature; within its own idioms it swings as well as wails. Set near the end of the 19th century, when a group of peasants have demanded basic rights from a landowner and soldiers arrive on horseback, it’s composed of less than 30 shots, each one an intricate choreography of panning camera, landscape, and clustered bodies. Jancso’s awesome fusion of form with content and politics with poetry equals the exciting innovations of the French New Wave in the 60s and early 70s. The music, ranging from revolutionary folk songs to {Charlie Is My Darlin’,} will keep playing in your head for days, and the colors are ravishing. The picture won Jancso a best director prize at Cannes, and it may well be the greatest Hungarian film of the 60s and 70s, summing up an entire strain in his work that lamentably has been forgotten here. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 1, 1998). — J.R.

The words “communist musical” may call to mind tractors and factories — both of which are certainly in evidence here — but this fascinating and enjoyable 1996 documentary by Romanian-born filmmaker Dana Ranga and American-born independent Andrew Horn presents the singular genre as a conflict between capitalist glitz and socialist poetry, revealing both the Marxists’ tragicomic attempts to beat the West at its own game and the homegrown folksiness of their efforts. Reportedly only 40-odd musical features were produced in the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Poland, and Romania prior to the collapse of communism, and roughly half of them are excerpted here. Ranga and Horn interview writers, directors, stars, and ordinary viewers of communist musicals, as well as one prestigious film historian (Maya Turorskaya, best known here for her book on Andrei Tarkovsky). The selection of clips isn’t everything it might have been — I regret the absence of any examples by Alexander Medvedkin, some of which are glimpsed in Chris Marker’s The Last Bolshevik, and eastern European critics have cited other omissions. But Ranga and Horn’s insights into communist film production and their story of how the communist musical triumphed or withered in its various settings offer plenty of food for thought. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 1, 1998). — J.R.

A middle-aged man who’s contemplating suicide drives around the hilly, dusty outskirts of Tehran trying to find someone who will bury him if he succeeds and retrieve him if he fails. This minimalist yet powerful and life-enhancing 1997 feature by Abbas Kiarostami (Where Is the Friend’s House?, Life and Nothing More, Through the Olive Trees) never explains why the man wants to end his life, yet every moment in his daylong odyssey carries a great deal of poignancy and philosophical weight. Kiarostami, one of the great filmmakers of our time, is a master at filming landscapes and constructing parablelike narratives whose missing pieces solicit the viewer’s active imagination. Taste of Cherry actually says a great deal about what it was like to be alive in the 1990s, and despite its somber theme, this masterpiece has a startling epilogue that radiates with wonder and euphoria. In Farsi with subtitles. 99 min. (JR)

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 25, 1998). — J.R.\

This unusually charming and touching Ismail Merchant-James Ivory film feels closer to memoir than fiction; it’s drawn from an autobiographical novel by Kaylie Jones (daughter of novelist James Jones), but Ivory, working with his usual screenwriting collaborator, Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, reportedly fleshed out the story with some of his own experiences. In “Billy,” the first of the film’s three sections, an expatriate novelist in Paris (Kris Kristofferson) and his wife (Barbara Hershey) adopt a six-year-old French boy who’s initially resented by the couple’s natural daughter. “Francis,” set a few years later, recounts the daughter’s friendship with an eccentric American schoolmate (Anthony Roth Costanzo), and Jane Birkin has a field day as his doting single mother. Yet these last two characters, as well as the family’s maid (Dominique Blanc) and her boyfriend (Isaac de Bankole), disappear in “Daddy,” which follows the family’s return to the States once the siblings are teenagers and the father’s health is deteriorating. The three parts add up to a rather lumpy narrative, and the characters are perceived through a kind of affectionate recollection that tends to idealize them, but they’re so beautifully realized that they linger like cherished friends. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 5, 1999). — J.R.

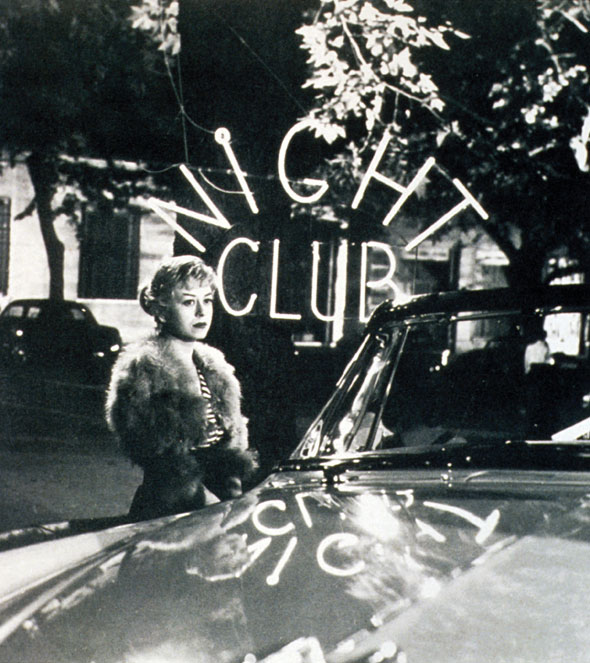

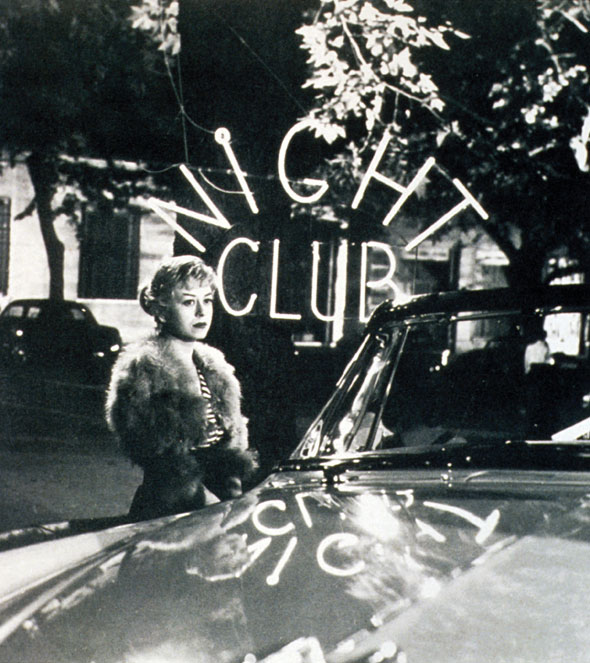

Raul Ruiz’s first mainstream release, which is getting its Chicago premiere at an art house rather than a multiplex, may not be one of his best — given his hundred or so shorts and features, there’s a lot of competition, and this is one of the rare Ruiz movies scripted by someone else. But it certainly provides some provocative and enjoyable jolts. Anne Parillaud plays a professional assassin in Seattle who dreams she’s a vulnerable newlywed honeymooning in the Caribbean and recovering from a rape; she also plays a vulnerable bride who dreams she’s an assassin. William Baldwin plays the significant other of both women, bearing the same name, and the contrapuntal play between Parillaud the victimizer and Parillaud the victim is pushed to dizzying extremes. Beautifully shot by Robby Muller, with periodic allusions in the score (by Ruiz regular Jorge Arriagada) to Bernard Herrmann’s work for Hitchcock, this head-scratching thriller should keep you entertained throughout, at least if you’re feeling adventurous. Ruiz didn’t even have final cut, but he clearly enjoyed himself making this film. Duane Poole wrote the distinctly Ruizian script, featuring twists at every turn, and the costars include Graham Greene and Bulle Ogier. Read more