From Film Comment (May-June 1973). — J.R.

LES IDOLES, Marc’O’s film version of his theater piece, originally opened in Paris in May, 1968, when many of its spectators were out in the street and presumably had other things to think about. It was released again early this year; but after a nominal run in one of several new mini-cinemas that have springing up lately all over the Left Bank, it seemed to vanish into oblivion a second time, only to re-emerge in a neighborhood house in early February, where it is currently playing. Talent does usually seem to find a way to reassert itself. Marc’O’s sarcastic parody about the making and merchandising of pop has nothing particularly profound or original to “say” about its subject, but it happens to have three of the liveliest performances in the modern French cinema.

Bulle Ogier, Jean-Pierre Kalfon, and Pierre Clementi, as the three pop stars, dive into their parts with such enthusiasm and expertise that the screen comes alive with their electric energies, and one can only speculate on how much more spectacular they must have been on the stage. (Despite some clever attempts at adaptation, LES IDOLES stubbornly remains another variant of filmed theater — a good thing to have, under the circumstances, but like Shirley Clarke’s ingenious recording of THE CONNECTION, it cannot really offer an equivalent to the excitements of a live performance.) A theoretical problem about parodying French rock is the fact that, at least to American ears, most of it tends to sound like parody anyway; but Ogier, Kalfon, Clementi overcome this obstacle with dazzling variations on the very notion of Star Presence. Clementi’s Mick Jagger imitations are somewhat less inspired, but are still marvelous fun to watch; Ogier intermittently captures and squeezes the soul of yê-yê until it squeaks; and in one virtuoso comic number, apparently Lewis-inspired, Kalfron beats his own master by leagues in evocations of sheer hysteria. And as extra added attraction, Bernadette Lafont makes an engaging guest appearance a singing nun at a pop wedding.

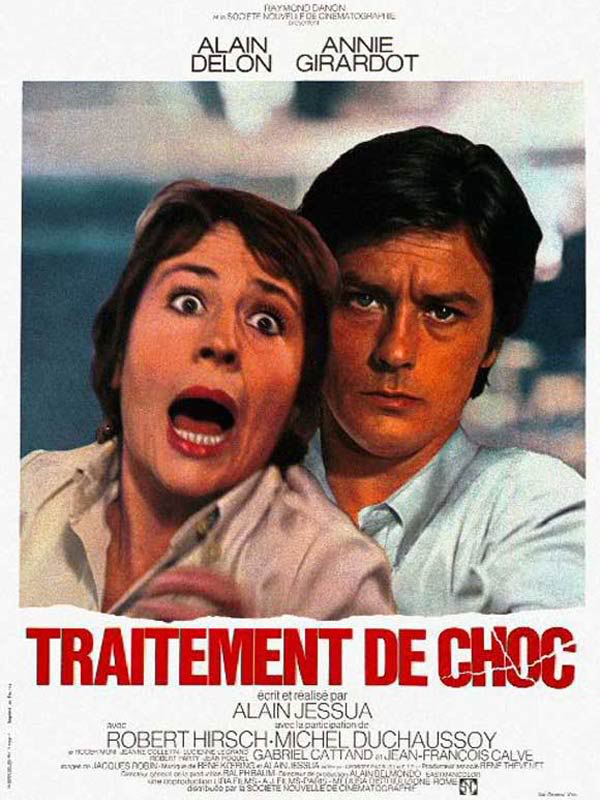

TRAITEMENT DE CHOC. Alain Jessua’s feature, starring Annie Girardot and Delon, is a somewhat sympathetic but — after LA VIE A L’ENVERS (LIFE UPSIDE DOWN) and JEU DE MASSACRE (THE KILLING GAME) — a considerable disappointment. Six years have elapsed since Jessua shot his second film (which is probably his best), and according to recent interviews, at least four of these years were spent in America, where Jessua tried in vain to get several film projects off the ground, notably a science-fiction script called “The Blue Planet” and a political film called “The White Panthers.” Although it is useless to speculate on whether any particular aspects of the older projects found their way into TRAITEMENT DE CHOC, the new film does attempt to cross-breed a science-fiction horror plot with a political allegory, and the virulence of the central premise does suggest that Jessua has more than a few fish to fry.

Annie Girardot arrives at the super-luxurious Institut de Thalassothérapie on the picturesque Belle-Ile-en-Mer. The sanitarium, presided over by Doctor Delon, resembles a ritzy resort, and offers experimental treatments designed to relieve depression and bring back the patients’ youth. As she starts undergoing the treatments, and acquaints herself with the other rich clients, Delon, and a few of the Portuguese immigrants who are working on the premises at menial jobs, she begins to notice strange things going on around her, etc., etc., until a Grand Guignol denouement reveals that the Portuguese workers are being drugged and disemboweled, in order to provide her and the other privileged clients with fresh cells — at which point she stabs Delon to death in his nether regions with a syringe. I’d feel a little less guilty about unveiling this “surprise ending” if Jessua himself hadn’t given the game away with such ostentatious, camera-nudging hints in the first reel; and although his horrific climax does manage to provide a few jolts — à Ia Franju, but without the poetry — the effect is marred by the use of an unconvincing dummy of a Portuguese cadaver that is too silly even to qualify as a Roger Corman reject, and winds up provoking at least as many giggles as shivers.

Jessua’s allegorical message, and his more specific assaults against many of the assumptions of modern medicine, are strong and persuasive, at least in theory, but they tend to be worked out pretty laboriously on the screen. The additional problems of locating a potentially radical statement within a patently commercial framework become insuperable, and too many banalities and frivolities — none of them objectionable in themselves — keep getting in the way: a bossa nova score that is intended to relate to the Portuguese characters, brief glimpses of Delon and Girardot in frontal nudity . . . just the sort of thing to keep the paying customers happy — and TRAITEMENT DE CHOC is currently pulling in more customers than any other first-run film in Paris — but they compromise the blunt edges of the critique, and all but reduce Jessua to a superior version of Dr. Delon, who also has ideals and seeks to please his clients.

Each of Jessua’s three features deals with some form of mental aberration that is treated rather abstractly. If the social aberrations that are covertly dealt with in TRAITEMENT DE CHOC had been handled less abstractly, the protest might have registered a lot more meaningfully. As it is, the Portuguese workers seem to wind up being servants and victims of the plot, as well as of the hospital — faceless devices in the service of both mechanisms, which the presence of the phoney-looking dummy only helps to spell out.

According to standard marketing procedures, a film is “new” in relation to when it is released, not when it is made. Sometimes this can work in a filmmaker’s favor: Tati’s PLAYTIME, still unreleased in the states, is newer than TRAFIC, and I’m told that several people who saw it at the last San Francisco Film Festival assumed it had been made afterwards, not four years before. The fact that LA NUIT DU CARREFOUR, a thriller shot by Jean Renoir forty-one years ago, has not yet been released in the U.S., thus entitles me to announce it as a new Renoir film. But even without this rather tenuous argument, it is probably the newest French film I’ve seen since PLAYTIME or L’AMOUR FOU — that is, the most alive to the future possibilities of cinema. I don’t even think it would be exceptionally perverse to call it, after LA RÈGLE DU JEU, the most exciting film in the entire Renoir canon. Yet apart from fairly regular screenings at the Cinémathèque, I don’t know of anywhere else in the world where it’s possible to see it.

This early sound adaptation of a Georges Simenon mystery (entitled Maigret at the Crossroads in English translation) might well qualify as the blackest film noir in the French cinema: black in its creepy nocturnal moods; black in its characters, which include as many poetic oddball types as one could find in THE OLD DARK HOUSE; and black in its extremely confusing, quasi-paranoid plot, with the sort of missing explanations of who killed whom and why that characterize THE BIG SLEEP (although Simenon’s novel, unlike Chandler’s, clears up most of the confusion). But perhaps what is most remarkable about the film is its unprecedented use of direct sound.

The soundtrack and its articulations are crucial to the narrative from the very beginning. During the credits, a musical theme that subsequently figures directly in the plot — a gramophone record played by the leading female character (Winna Winfried) — alternates with the abrupt, brutal noises (and accompanying images) of a car motor, a sautering iron, and shots from a pistol: a précis of key sounds in the film. But in order to understand the function of sound in the story proper, it is necessary to consider the visual style it plays against: an elliptically cut give-and-take between dark exteriors and smokily lit interiors that keeps most of the characters, settings, and plot in a mysterious moral and spatial limbo. In such an impenetrable atmosphere, even Inspector Maigret (Pierre Renoir) fumbles in his search to solve a pair of murders. But if the lighting and cutting are respectively expressionist and metaphysical in effect and implication, the direct sound is neo-realist and concrete, constantly locating and leading us into specifics of locale and plot that the visual style usually obscures.

Most of the action centers around a truck stop, garage, and neighboring houses. Early in the film, when Maigret and an assistant stand conversing on a street, the increasing volume of a car that approaches from off-screen sets up a contrapuntal tension worthy of Hitchcock (the car nearly runs them down) and establishes a strong sense of spatial depth beyond the frame that transforms the nature of what we see. (For an interesting consideration of sound used in an antithetical way, to dislocate the spectator in relation to the image, cf. Phyllis Goldfarb’s analysis of TOUCH OF EVIL in “Orson Welles’s Use of Sound,” Take One, Vol. 3. No. 6.) Elsewhere, repeated sounds of water dripping from a faucet, accented by brief cutaways to the source, play against the rhythms of a police interrogation, as do shots of newspaper headlines from various editions about the murder in question, which we see and hear being swept away by water into a gutter; heavy rain persists throughout much of the action around the truck stop, and the sounds of pans catching leaks add an unnerving obbligato to several other scenes. The grating noise of a mechanic sharpening a tool interferes — deliberately, as we later discover — with a phone call Maigret tries to make in the garage, and additional aural colorations are provided by the strange foreigh accents of Georges Koudria and Winna Winfried.

I don’t mean to suggest that all my enthusiasm for LA NUIT DU CARREFOUR is based on strictly formal elements. Winna Winfried’s vamp performance happens to be one of the sexiest things I know of in the French cinema, and I would gladly choose its eroticism over that of every film cited in FILM COMMENT’S recent “Cinema Sex” issue — although, admittedly, pornography often has a lot more to do with science (instruction) than art (eroticism). And there’s a car chase through winding streets at night-shot from the front of the car in pursuit, in virtually a single take — that is one of the purest and loveliest kinetic pleasures that Renoir has ever given us. Come to think of it, that’s pretty sexy too.