These program notes for a John Cassavetes retrospective in July 1980 were commissioned by the Museum of Modern Art’s Film Department, which as I recall edited them fairly substantially. (My subsequent “review” of the retrospective for The Soho News, “The Tyranny of Sensitivity,” is already available on this site.) I no longer have the unedited version, but I’ve tweaked this version in a few spots for style as well as factual accuracy without altering any of its opinions, some of which I might no longer share. -– J.R.

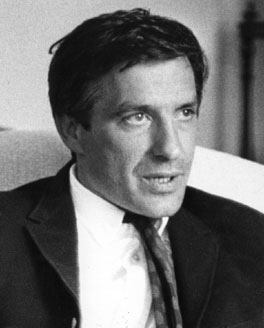

JOHN CASSAVETES, FILMMAKER AND ACTOR

June 20–July 11, 1980

“I Can’t Give You Anything But Love,” the cornball anthem that sounds so memorably through the final moments of Cassavetes’ THE KILLING OF A CHINESE BOOKIE, might be a fair enough theme song for what his contribution to movies is all about: a radical commitment to people that goes beyond mere thought.

His attitude is one that often has been difficult to grasp, for in over three decades as director, writer, and actor, he has seldom encouraged, or even allowed, a detached appraisal. For someone like me, who grew up watching his performances in films and live TV dramas in the fifties before experiencing the raw shock and revelation of SHAD0WS in 1961, a disinterested account of what that shock meant is perhaps impossible. In addition, recent second looks at SHADOWS and TOO LATE BLUES have pointed up for me just how easy it was to be confused about the nature and value of the director’s achievement. Today it remains difficult to come to terms with his work. 0n one level, it probably is no exaggeration to say that most of his films trace a range between the incandescent and the unbearable, in more ways than one.

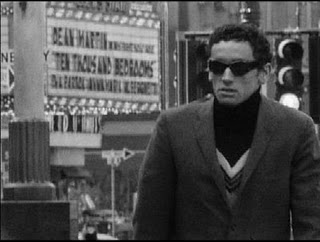

In 1961, SHADOWS was a populist miracle. A 16mm film costing only 940,000 (furnished largely by mailed-in donations after Jean Shepherd made an appeal on his late-night radio show), and originally improvised by members of Cassavetes’ acting class (including Hugh Hurd, Lelia Goldoni, Ben Carruthers, Anthony Ray, and Rupert Crosse) without a script, it inevitably — and somewhat misleadingly — became associated in the public mind with early New Wave films that were roughly contemporaneous with it, like BREATHLESS and THE 400 BLOWS.

Perhaps the aspect of that association which seems most relevant today is the exhilarating freedom of low-budget location shooting. (As a portrait of midtown Manhattan in the late, beat fifties – from Port Authority Bus Terminal to Central Park, with many stopovers en route — SHAD0WS remains an indelible and evocative record, just as BREATHLESS gives us glimpses of a now-vanished Paris from the same period.) What could not have been apparent at the time is how fully SHAD0WS, for all its supposedly improvised aspects, introduces Cassavetes as an auteur, setting down themes, attitudes, and structures that recur throughout his work. Consider such details as the macho horsing around and the intercut mating rituals depicted in the opening sequence, the rabid anti-intellectualism of the “literary party” (which looked, alas, as unconvincing in 1961 as it does today, even as satire), and the post-coital depression of the heroine Lelia, and it will not be hard to find counterparts in later Cassavetes films.

It wasn’t until 1968, with FACES, that Cassavetes made a commercial breakthrough as a director — long after his unhappy experiences as a contract director for Paramount (T00 LATE BLUES) and Stanley Kramer (A CHILD IS WAITING) in the early sixties. One of the pleasures of this retrospective is the opportunity to reassess such neglected, flawed, yet awesome early works as his two jazz-related films, SHADOWS and TOO LATE BLUES. Think of the radically different show-biz managers depicted in these movies, Rupert Crosse in SHADOWS and Everett Chambers in TOO LATE BLUES — extraordinary creations, as richly imagined, as complexly felt and realized, as any characterizations that I know of in American films: magic conceptions and performances that continue to astonish not only for what they reveal, but also for what they indirectly indicate that other films deny and ignore. If, in TOO LATE BLUES, Chambers’ character has to get to us through some unfortunate dialogue and plot construction –- not an isolated problem in Cassavetes, work — this makes it no less visibly triumphant in its lasting impact.

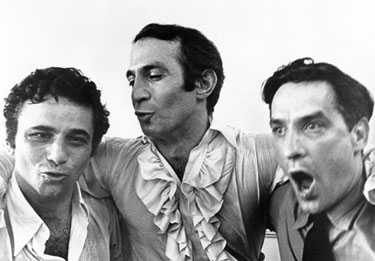

An intuitive director even more perhaps than Howard Hawks or Robert Altman, Cassavetes scores most often in precisely those areas where more “thoughtful” directors with stronger overall conceptions (or preconceptions) flounder. FACES remains a fascinating and powerful depiction of middle-class sexual discontent and embarrassment as long as it allows its talented actors — Gena Rowlands, John Marley, Lynn Carlin, Seymour Cassel — to make legitimate self-discoveries within that framework. When it tries to conceptualize its own achievement (as in the awkward prologue), or exploit its discoveries by using them to sell a thesis (as in the compulsive use of convulsive laughter), it characteristically operates more like a bludgeon. This last tendency achieves its least attractive effects in the self-indulgent misogynist antics of the male trio (Peter Falk, Ben Gazzara, and Cassavetes himself) in HUSBANDS, a literal and figurative spinoff of some of the more questionable aspects of FACES.

Cassavetes’ most memorable performances as an actor tend to be in uncharismatic and/or villainous parts (as in THE DIRTY D0ZEN, ROSEMARY’S BABY, THE FURY, or Elaine May’s brilliantly scripted MIKEY AND NICKY — a corrosive, neglected work not in this program). Paradoxically, uncharismatic villains are pointedly absent from the films he has directed and written. (Figures of ridicule, such as the “intellectual ” David in SHADOWS or some of the hapless females in HUSBANDS, are mainly stooges, not villains.)

After another attempt to adapt his loose methods with actors to a more commercial, mainstream context, in the pleasant if relatively minor MINNIE AND MOSKOWITZ (1971) featuring his wife Gena Rowlands and his longtime friend and associate Seymour Cassel, Cassavetes returned to a more exploratory mode in the powerful and disturbing A WOMAN UNDER THE INFLUENCE, starring Rowlands and Falk. Perhaps no other major Cassavetes movie exposes so clearly the strengths and the problems of his methods. The danger is that of presenting an audience with a tabula rasa on which one is virtually invited to find one’s own biases and preconceptions confirmed. Hence the unpersuasive feminist readings that have been given to this film, along with equally unconvincing responses that take a reverse tack — both positions reflecting nothing more than a spectator’s personal identification with one character or another, or one character versus another. It’s a response that Cassavetes’ approach — like that of Elia Kazan and other Method-influenced directors — explicitly encourages, and it can easily provoke, on the part of the spectator, a form of self-flattery that passes itself off as understanding.

After the considerable commercial success of A WOMAN UNDER THE INFLUENCE, Cassavetes’ next film, THE KILLING 0F A CHINESE BOOKIE, died almost instantaneously at the box office. It was subsequently re-edited by the director, in a shorter version that will be shown in this retrospective. Having seen only this second version (which was shown at the 1976 London Film Festival), I can’t compare it with its predecessor, but can nevertheless recommend it as one of the most touching and memorable films in the Cassavetes canon (and one to which Peter Bogdanovich’s SAINT JACK, featuring a similar central performance by Ben Gazzara, apparently owes more than a little).

OPENING NIGHT, the most recent of Cassavetes’ completed features, has already opened in Los Angeles and London; its failure so far to get a New York release seems due, at least in part, to the relatively narrow range of local critical tastes that makes this city the provincial “last stop” for a good many offbeat pictures. A movie that in some respects demands as much indulgence as does its leading character Myrtle Gordon (Gena Rowlands), it also delivers the kind of ferocious, sweaty energy that we get from the other Cassavetes-Rowlands collaborations – with memorable contributions by Gazzara, Cassavetes, Joan Blondell, Paul Stewart, and Zohra Lampert, making it a good deal more than a star vehicle. Just as THE KILLING OF A CHINESE BOOKIE begins as a thriller only to co1lapse (or expand) into yet version of Cassavetes’ Chekhovian humanism, OPENING NIGHT broaches the sort of self-conscious material about theatrical representation to be found in, say, Pirandello or Rivette, only to transform its modernist potentialities into the same kind of pure behaviorism towards which Cassavetes’ other movies gravitate. (And unlike the poetic fantasy introduced by, say, Fellini to help describe a midlife crisis, Cassavetes’ literal fleshing-out of Myrtle’s fantasy projections tends to be direct and prosaic. As unwieldy as ever, Cassavetes’ structures continue to give us moments – actors’ moments — that no other director can approximate. As critic Tom Milne pointed out with reference to OPENING NIGHT, this makes a Cassavetes movie virtually impossible to synopsize -– often a promising sign –- “since its dense emotional texture is woven out of a network of hints and allusions that fall apart as soon as they are pinned down in words.”

— JONATHAN ROSENBAUM