Chen Kaige clearly intended this Chinese fantasy-action spectacle to top Zhang Yimou’s Hero, and I must admit that I prefer it to the earlier movie: the digital effects are sometimes excessive, yet Chen’s story of a loyal slave, his master, and a wealthy, seemingly doomed princess is more affecting, especially in the closing stretch. Chen’s original U.S. distributor, the Weinstein Company, ordered him to shorten the movie from its original running time of 128 minutes and then dropped it. (It’s worth recalling that his 1996 feature Temptress Moon was severely damaged by Miramax’s recutting.) Now Warner Independent Features is releasing the abbreviated, 102-minute version, and it’s well worth checking out. PG-13. Century 12 and CineArts 6, Esquire, Landmark’s Century Centre.

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (November 25, 1994). — J.R.

* MARY SHELLEY’S FRANKENSTEIN

(Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Kenneth Branagh

Written by Steph Lady and Frank Darabont

With Kenneth Branagh, Robert De Niro, Helena Bonham Carter, Tom Hulce, Aidan Quinn, Ian Holm, Richard Briers, and John Cleese.

* JUNIOR

(Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Ivan Reitman

Written by Kevin Wade and Chris Conrad

With Arnold Schwarzenegger, Danny DeVito, Emma Thompson, Frank Langella, Pamela Reed, and Judy Collins.

Through a perverse coincidence, Kenneth Branagh and his wife, Emma Thompson worked simultaneously, on separate continents, on two lousy features about men usurping the reproductive roles of women. In many respects, these movies are radically different: Branagh’s pre-Thanksgiving turkey, misleadingly titled Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, is the umpteenth screen adaptation of what is arguably one of the greatest feminist novels and perhaps the first serious example of science fiction. Thompson’s movie, a Thanksgiving release, is a Ivan Rietman “family-values” fantasy-comedy about Arnold Schwarzenegger becoming pregnant — a high-concept obscenity that seems inspired by the combined successes of Twins (which also starred Schwarzenegger and Danny DeVito) and Tootsie (which also contrived to show how men make better women than women, a project also taken up by The Crying Game). Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 10, 1989). — J.R.

TAP

** (Worth seeing)

Directed and written by Nick Castle Jr.

With Gregory Hines, Suzzanne Douglas, Savion Glover, Joe Morton, Dick Anthony Williams, “Sandman” Sims, Bunny Briggs, and Sammy Davis Jr.

One of the more poignant effects of contemporary Hollywood has been the virtual extinction of at least two of the major genres that served as industry staples during the 30s, 40s, and 50s: the western and the musical. When attempts are made to resurrect these old standbys, a certain self-consciousness often makes itself felt. Such “last westerns” as Once Upon a Time in the West and McCabe and Mrs. Miller, and such “last musicals” as All That Jazz and Pennies From Heaven tend to wear their obsolescence on their sleeves, representing themselves as last-ditch attempts to revivify forms that are no longer part of the present tense, but only nostalgic emblems of an earlier era.

Other recent approaches, however, have avoided such self-consciousness, and behaved as if the genres in question never really left us. Young Guns was a fairly forgettable attempt to bring back the western that populated a conventional example of the genre with several youthful male stars. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 7, 1989). — J.R.

GREAT BALLS OF FIRE

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Jim McBride

Written by Jack Baran and McBride

With Dennis Quaid, Winona Ryder, Alec Baldwin, John Doe, Lisa Blount, Stephen Tobolowsky, and Trey Wilson.

Given that Jim McBride’s film debut was a pseudodocumentary designed to look real (David Holzman’s Diary, 1968), and was followed by an actual diary film that was made to seem fictional (My Girlfriend’s Wedding, 1969), it should be no surprise that Great Balls of Fire, which purports to be a biopic of rock-and-roller Jerry Lee Lewis, is actually a musical-comedy fantasy about virtually imaginary characters.

For those who accept the a priori assumption that most movies are simply dreams and lies, this is only business as usual; in fact, in playing fast and loose with the facts McBride and his longtime collaborator Jack Baran are working in a grand tradition peopled by the makers of most other simpleminded Hollywood biopics. The difference here is that the falsity of their concoction is made nakedly apparent: at least two-thirds of the picture resembles a feature-length music video, patterned in some ways after the rock musicals of 30 years ago. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 2, 1993). For all my enthusiasm back then, I can’t remember any of this film now. This is one of the unfortunate side-effects of regular reviewing, which nearly always involves a certain amount of hype (in convincing both readers and one’s self that this week’s offerings are important and notable) and a certain amount of forgetting (that you both went through the same song and dance a week ago). — J.R.

HOUSE OF CARDS

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Michael Lessac

With Kathleen Turner, Tommy Lee Jones, Asha Menina, Shiloh Strong, Esther Rolle, and Park Overall.

If one of the surest signs of story-telling talent is the capacity to put across an outlandish plot, the first feature of writer-director Michael Lessac is impressive — riveting, exciting, and oddly believable on its own provocative terms throughout. On the page, however, it may sound contrived and pretentious, bordering on some new-age brand of science fiction. So if you want a story that unfolds with all the dramatic force and internal logic needed to compel suspension of disbelief, go see House of Cards before you hear very much more about it, including what I have to say below. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 1, 1993). — J.R.

The second feature in Sergei Eisenstein’s controversial, unfinished trilogy, also known as The Boyar’s Plot, with a Prokofiev score and a histrionic, campy (albeit compositionally very controlled) performance in the title role by Nikolai Cherkassov (1946). The ceremonial high style of the proceedings has been interpreted by critics as everything from the ultimate denial of a cinema based on montage (under Stalinist pressure) to one of the most courageous acts of defiance in film history (Joan Neuberger and Yuri Tsivian) to the greatest Flash Gordon serial ever made (my own estimation). The second part climaxes in a dazzling, drunken dance sequence that features Eisenstein’s only foray into color. Thematically fascinating both as submerged autobiography and as a daring portrait of Stalin’s paranoia, quite apart from its interest as the historical pageant it professes to be, this is one of the most distinctive great films in the history of cinema — freakishly mannerist, yet so vivid in its obsessions and expressionist angularity that it virtually invents its own genre. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From Film Comment (November-December 2010). — J.R.

Another Fine Mess: A History of American Film Comedy

By Saul Austerlitz Chicago Review Press, $24.95

As an audacious and ambitious canonizing gesture, this highly readable critical volume comes closer to Sarris’s The American Cinema than it does to Thomson’s Biographical Dictionary of Film, if only because the author can always be counted on to have seen the work he writes about. Omissions are of course inevitable, and even though I don’t know Austerlitz’s age, I suspect that most of the lacunae I notice in the creative figures he selects for his 30 chapters and 105 shorter entries — such as Fred Allen, Danny Kaye, Martha Raye, and Red Skelton — are generationally determined for both of us; older and younger readers will come up with other missing names. But the amount that he actually covers is impressive.

Sometimes the organizational strategies get weird: the chapter on Dustin Hoffman, delving perceptively into the Jewish aspects of his persona, also manages to be a chapter about Warren Beatty. Some of the research is sloppy: Orson Welles couldn’t have “credited” The Power and the Glory as an “inspiration” if he maintained that he’d never seen it. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 1, 1988). The stills are copyrighted by the Estate of Andrew Noren. — J.R.

Andrew Noren’s first film since Charmed Particles offers 59 minutes of ecstatic delight in relation to the everyday: it’s all black and white and silent, and mainly nonnarrative, but so sensually rich and rhythmically alive that watching it is an almost constant pleasure. Noren calls himself a light thief and shadow bandit, and this pulsing compendium of home-movie moments is charged with musical energy. It differs from Charmed Particles, the previous episode in his The Adventures of the Exquisite Corpse, mainly in seeming to have more thematic ambitions and in verging somewhat closer to narrative — none of which is allowed to detract much from the overall beauty and intensity of the filmmaking. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From Cineaste, Vol. XXXI, No. 4, September 2006. — J.R.

Spoilers ahead: The title heroine (Silvia Pinal) of

Luis Buñuel’s masterpiece, a Spanish novice

about to take her final vows, is ordered by her

mother superior to visit her rich uncle (Fernando

Rey), Don Jaime, who’s been supporting her over

the years but whom she barely knows. A

necrophiliac foot fetishist, he’s preoccupied with

how closely his beautiful niece resembles his

late wife, who died tragically on their wedding night,

and somehow manages to persuade Viridiana

to put on her wedding dress, which he’s

faithfully preserved. With the help of his servant

Ramona (Margarita Lozano), he then drugs her with the

intention of raping her, but deeply mortified by

his behavior, ultimately holds back and hangs

himself instead, using the skipping-rope he

previously gave to Ramona’s little girl.

If this opening strongly evokes the horror of a

Gothic novel — a form of literature Luis

From the Chicago Reader (February 27, 1998). — J.R.

The Gingerbread Man

Rating * Has redeeming facet

Directed by Robert Altman

Written by John Grisham and Al Hayes

With Kenneth Branagh, Embeth Davidtz, Robert Downey Jr., Daryl Hannah, Tom Berenger, and Robert Duvall.

Some people are going to go to The Gingerbread Man looking for a John Grisham movie, and some are going to go looking for a Robert Altman film. Both are likely to be disappointed.

The alliance may have been a shotgun marriage presided over by desperate commerce, though the movie’s press book works overtime trying to put a positive spin on it: “Both Altman and Grisham champion the causes of Everyman underdogs who are fighting the system. Indeed, in their own different ways, these two artists are mavericks, outsiders-by-choice who examine a system and an orderly regimen that they have long ago abandoned. John Grisham left a successful legal practice for an even more lucrative literary career based in large part on his ability to accurately depict the shortcomings of our legal system and the behind-the-scenes machinations that are a routine part of that profession. And against considerable odds, Robert Altman has bucked the Hollywood establishment for 30 years, continuing to make distinctly personal movies exactly the way he wants to make them, ignoring the marketing driven, lowest-common-denominator sensibilities that seem to determine which studio films actually get made.” Read more

From The Financial Times (Friday, July 2, 1976). This was the second and last time that I took over Nigel Andrews’ weekly film column while he away. — J.R.

Bambi (U)

Odeon, St. Martin’s Lane

Lifeguard (AA)

Ritz

When the Leaves Fall

National Film Theatre

Thirty-four years have passed since Walt Disney’s Bambi first hit the screen. Yet barring only its quaintly dated musical score – six unremarkable tunes by Frank Churchill and Edward Plumb that are well below the usual Disney standard – an unsuspecting child who can’t read Roman numerals might assume that it was made yesterday. It is no small irony that a movie only slightly more than half as old, Silk Stockings (1957), gets treated like a museum piece worthy of nostalgia in the recent That’s Entertainment Part II, while this animated feature gets born afresh for each new generation – not so much like a phoenix rising out of its ashes as like a display of calendar art circulated periodically, with only the dates changing. Read more

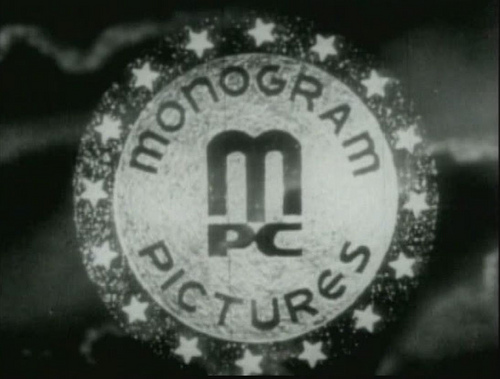

Written in 2007 for Criterion, as the commentary for a DVD extra. — J.R.

“As a critic, I already thought of myself as a filmmaker” Godard said in 1962. “Today I still consider myself a critic, and in a sense, I’m even more of one than before. Instead of criticism, I make a film, but that includes a critical dimension. I consider myself an essayist, producing essays in the form of novels or novels in the form of essays: only instead of writing, I film them.”

Three years before he said this, Godard made the first shot in his first feature, appearing just before the title, the explicit declaration of a film critic: “This film is dedicated to Monogram Pictures.”

Why Monogram? Godard never reviewed anything from that studio, which lasted from 1931 to 1953 and mainly produced cheap westerns and series like the Bowery Boys. But shooting on the fly and without sync sound, he wanted to express an alliance to an aesthetic related to impoverished budgets. So this wasn’t any sort of fan’s homage, as it would have been if it had come from one of the American movie brats; it was a critical statement of aims and boundaries. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 19, 1991). — J.R.

JU DOU

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Zhang Yimou, in collaboration with Yang Fengliang

Written by Liu Heng

With Gong Li, Li Baotian, Li Wei, Zhang Yi, and Zheng Jian.

Like most people reading this, I know next to nothing about the history of China, which is thousands of years older than the U.S. and has a population over four times as large. In high school I was required to take courses in Alabama and American history; world history was an elective, but if that course had anything to do with China, I no longer recall any details. I also managed to get through seven years of college and graduate school without further edification on the subject.

I suspect that most people in China are comparably uninformed about the U.S. When my youngest brother was in Kenya in the late 60s, he spent time conversing with some Red Guard members who were stationed there, and used to have friendly arguments with them about where Coca-Cola, which they liked, came from; they were convinced it was a product of Kenya. It was difficult for them to accept that anything they liked came from the U.S., Read more

Many of Steven Soderbergh’s better films seem to exist in the shadow of their predecessors. For all its freshness, Sex, Lies, and Videotape, his first feature, was a replay of many self-referential movies about movies dating from the 60s and 70s. The Underneath was a more direct remake, of the 40s noir Criss Cross, and it was an interesting variation rather than any sort of improvement. Yet part of what’s so good about The Limey (1999, 91 min.), a contemporary thriller starring Terence Stamp as an ex-con avenging the death of his daughter, is the way it evokes Point Blank, which is still John Boorman’s best movie. The complex play with time, the metaphysical ambiguity, the stylish wit and violence, and the cool sense of LA architecture all evoke that singular Lee Marvin vehicle. For that matter, a lot of flashback material about the hero as a young man comes straight out of Ken Loach’s Poor Cow (1967). But with or without a sense of where it all comes from, this is a highly enjoyable and offbeat thriller — better to my taste than Soderbergh’s Out of Sight, though similarly quirky in how it sets about telling a story. Read more

From Nashville Scene (cover story), March 10, 2011. This essay was commissioned by the late Jim Ridley, whose unexpected death was a grievous loss.

I’m sorry that I forgot to mention The Young One, surely one of the most neglected and overlooked of all great Southern films, explored in detail elsewhere on this site. — J.R.

In certain respects, the “Visions of the South” series of Southern

movies being launched in Nashville this week at The Belcourt deserves

to be applauded for its omissions as well as its inclusions. The most

conspicuous of these omissions is probably Robert Altman’s Nashville

(1975), which Brenda Lee once aptly described as “a dialectic collage of

unreality.” (Altman, at least, proved better at handling Mississippi —

in Thieves Like Us the year before Nashville, and in Cookie’s

Fortune a quarter of a century later.)

We all know, of course, that Hollywood and even some of its maverick

celebrities have been guilty of fostering and/or perpetuating false images

of the South from the very beginning. A few other prominent and

dubious examples might include Jean Renoir’s The Southerner

(1945), Martin Ritt’s The Sound and the Fury (1959), Richard

Brooks’ Sweet Bird of Youth (1962), Otto Preminger’s Hurry

Sundown (1967), John Frankenheimer’s I Walk the Line

(1970), and, surely the most bogus of all, Alan Parker’s

Mississippi Burning (1989), with its outlandish errors

involving both Jim Crow and the FBI, just to get started. Read more