Written in 2007 for Criterion, as the commentary for a DVD extra. — J.R.

“As a critic, I already thought of myself as a filmmaker” Godard said in 1962. “Today I still consider myself a critic, and in a sense, I’m even more of one than before. Instead of criticism, I make a film, but that includes a critical dimension. I consider myself an essayist, producing essays in the form of novels or novels in the form of essays: only instead of writing, I film them.”

Three years before he said this, Godard made the first shot in his first feature, appearing just before the title, the explicit declaration of a film critic: “This film is dedicated to Monogram Pictures.”

Why Monogram? Godard never reviewed anything from that studio, which lasted from 1931 to 1953 and mainly produced cheap westerns and series like the Bowery Boys. But shooting on the fly and without sync sound, he wanted to express an alliance to an aesthetic related to impoverished budgets. So this wasn’t any sort of fan’s homage, as it would have been if it had come from one of the American movie brats; it was a critical statement of aims and boundaries.

The sort of American models Godard had in mind weren’t as modest as Monogram’s, but they resembled B films: Richard Quine’s Pushover (with Kim Novak in her first starring role, playing a femme fatale who turns the hero into a pushover) and Otto Preminger’s Where the Sidewalk Ends. Interestingly enough, both of these, unlike Breathless, are about police detectives who become corrupted. We also hear a bit of the soundtrack of Preminger’s Whirlpool when Jean Seberg enters a movie theater (and of course Preminger’s Bonjour Tristesse was the inspiration for Patricia). We get one poster of Humphrey Bogart, and two lines in the dialogue can be related to Dashiell Hammett: “I always fall for the wrong dames” (The Maltese Falcon, the movie) and a crack about wearing silk and tweeds together (The Glass Key, the novel).

The last, of course, is a literary quote, and the most important aspect of Godard’s film culture is how closely it’s tied to ideas about literature, philosophy, music, and painting. Here the references to art and literature (such as Picasso and Faulkner) are mainly tied to Patricia and the film references are mainly tied to Michel; but both characters seem equally connected to existential philosophy. When Patricia says that it’s never dark enough when she shuts her eyes, this lusting after the void is both metaphysical and a line of dialogue remembered or misremembered from Ingmar Bergman’s Sommarlak, which Godard had already cited in a review of Douglas Sirk’s A Time to Live and A Time to Die.

We could also argue that the jump cuts in Breathless are existential in their implications (helping to account for Jean-Paul Sartre’s praise of the film), at least if we agree with critic Andrew Sarris that they function the same way as Josef von Sternberg’s slow lap dissolves — by indicating “the meaninglessness of the time intervals between moral decisions.” Following the philosophy of “anything goes,” rather like Michel himself, Godard employs jump cuts with seeming arbitrariness, as a way of remaking the cinema he loves, just as he employs archaic iris shots from the silent era.

His most explicit borrowing from another film, already celebrated in one of his reviews, comes from Samuel Fuller’s Forty Guns. In this 1957 Western, after a gunsmith played by Eve Brent starts flirting with Gene Barry while adjusting a made-to-order rifle for him, he playfully points the rifle at her and we see her framed through the gun’s barrel in a kind of impromptu iris shot. This image goes out of focus, and we cut to a medium shot of the two of them kissing. He says, “I never kissed a gunsmith before,” and she asks, “Any recoil?”

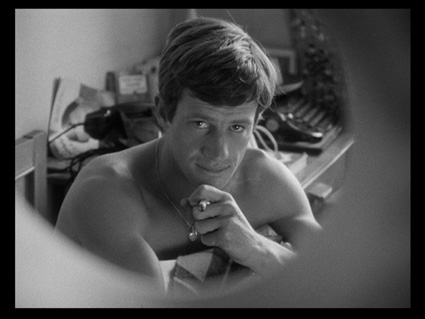

In Godard’s version — occurring about a third of the way through the film’s longest sequence, a 23-minute account of Patricia and Michel’s fluctuating relationshipin her hotel room — the sexes are reversed, and the woman is no longer the aggressor. Patricia rolls up a poster and gazes through it at Michel, who stares back in a self-conscious pose. Cut to a slow reverse zoom away from their kiss in closeup. Meanwhile the film’s score has shifted from Patricia’s lush romantic theme to Michel’s dry jazz piano theme. So the crucial moment of Patricia’s capitulation — not a moral decision, a romantic one —- has been elided. Godard, who’s been charting Michel’s attempted seduction of her for quite some time, leaps ahead to his victory.

Michel wins the battle, but not the war. Godard’s own macho position echoes his hero’s: women are betrayers, men pushovers. If Godard’s indebted to anyone in mapping out this masochism, this might be Jean-Pierre Melville, his major predecessor in crossbreeding the American-style thriller with the European art movie. Melville was also fascinated with America, accounting for his adopted last name, and also something of a dandy and autodidact, as can be seen when he turns up playing the novelist Parvulesco. There’s even an explicit reference to his first noir, the 1955 Bob le Flambeur — when Michel suggests that Bob Montagné could perhaps cash his check for him, only to be told, “He’s in the cooler, the idiot!”

The difference between fan and critic isn’t just a matter of aim but a question of temperament. Dizzy Gillespie attributed part of his trumpet style to his failure to imitate Roy Eldridge, and Faulkner similarly cited his failure to write romantic poetry as the basis for his prose style. As T.S. Eliot once wrote, “Between the emotion / And the response / Falls the shadow.” And it’s in the shadow between model and imitation that Godard’s criticism should be located. Three years after making his first feature, he said, ”Although I felt ashamed of it at one time, I do like Breathless, but now I can see where it belongs —- along with Alice in Wonderland. I thought it was Scarface.”