From my 2007 collection Discovering Orson Welles and the Chicago Reader (October 29, 1993). -– J.R.

I’m one of the people who receives an acknowledgment in the final credits of It’s All True: Based on an Unfinished Film by Orson Welles, but in fact I regret the contribution I made to this film. During a phone conversation with Bill Krohn, one of the writers, directors, and producers, Bill told me that one of the French producers, Jean-Luc Ormières, was looking desperately for a composer for the documentary who wouldn’t charge too much money. I suggested Jorge Arriagada — the Chilean film composer who at that point had written the scores for something like a couple of dozen films by Râúl Ruiz, a filmmaker I greatly admire as well as a friend — and Arriagada wound up getting hired for the job. I recall having heard that Arriagada mainly worked for Ruiz because he liked to do so rather than out of economic necessity, and this fact combined with Ruiz’s own Welles worship and Arriagada’s South American background made him seem ideal. Unfortunately, this conclusion was built on the common Anglo-American fallacy that Latin America is something like a single homogeneous culture — the same assumption, I presume, that years later would prompt Colin MacCabe, the producer at the British Film Institute of a series of national film histories on film or video assigned to various filmmakers, to assign the whole of Latin American cinema to one (admittedly very talented and knowledgeable) Brazilian director, Nelson Pereira dos Santos, yielding his 93-minute Cinema of Tears in 1995.

In this case, my assumption that Arriagada would have been well versed in samba and Brazilian pop music proved to be erroneous, and his score for It’s All True, whatever its own qualities, wound up having little to do with Welles’s original designs for the music. I’m fairly certain that if Dick Wilson — who’d been of inestimable help to me while I was editing This Is Orson Welles, all the way up to his tragic death in August 1991, while keeping his illness a secret from me — had still been alive, such an error would have been averted, because Dick was much more aware of and familiar with the specific music that Welles had in mind.

For much more material about It’s All True and Bill’s own work on it, see chapter 19. I should add that far and away the most valuable scholarly resource on It’s All True remains Catherine L. Benamou’s brilliant and definitive book on the subject, adapted from her dissertation, which I’ve read in manuscript and which will be published eventually by University of California Press, once Catherine allows this to happen. (The many delays and deferments, alas, have already been comparable in some ways to the releases of some of Welles’s unfinished films.) Meanwhile, Catherine has recently brokered the acquisition of two invaluable sets of papers by the University of Michigan, where she teaches — those of Welles that were in the possession of Oja Kodar, and those of Richard Wilson, Welles’s assistant and associate during much of the 30s and all of the 40s. (She has aptly named both collections “Everybody’s Orson Welles.”)

IT’S ALL TRUE: BASED ON AN UNFINISHED FILM BY ORSON WELLES

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Richard Wilson, Myron Meisel, and Bill Krohn

Narrated by Miguel Ferrer.

Too much effort and real love went into the entire project for it to fail and come to nothing in the end. I have a degree of faith in it that amounts to fanaticism, and you can believe that if It’s All True goes down into limbo I’ll go with it. — Orson Welles, writing to a Brazilian friend in the 40s

As perverse as it sounds, the work of art that It’s All True: Based on an Unfinished Film by Orson Welles most calls to mind — my mind, anyway — is Vladimir Nabokov’s 1962 novel Pale Fire. Discounting its tricky foreword and index, this literary tour de force consists of a 27-page, 999-line poem by the fictional dead poet John Shade, followed by 160 pages of annotation by the probably insane and certainly unreliable Charles Kinbote. By contrast, It’s All True consists of about half an hour of entertaining, accurate, and altogether sane commentary on Orson Welles’s ill-fated, three-part feature of that title, followed by an hour-long edited version of the silent rushes of one of the episodes, “Four Men on a Raft,” originally planned as the feature’s centerpiece. (Edited by Ed Marx, who used a few rough outlines by Welles as his main guide, this episode has been furnished with discreet sound effects and music by Jorge Arriagada, Raul Ruiz’s principal composer. The most significant part that’s missing — and I wish the documentary prologue had pointed this out — is the narration Welles planned to use but never wrote or recorded.)

One can easily tick off major differences between Pale Fire and It’s All True. What then are the similarities? An interdependence of text and commentary that keeps one’s mind restlessly scampering between the two, unable to find satisfaction or closure in either. The uncertainty and indeterminacy of the longer section of each work (Pale Fire‘s commentary, It’s All True‘s “text”), in contrast to the pithy clarity of the shorter section. The presentation of two complementary and stylistically divergent forays into the same genre (fiction in Pale Fire, documentary in It’s All True) that together say and mean more than either could alone, despite the fact that the synthesis is riddled with gaps and raises innumerable questions. Finally, an excruciating rift between what is present and what is absent — between the knowable and the unattainable, the graspable and the unimaginable.

In short, It’s All True generally does such a good job with what it has, journalistically speaking, that it winds up breaking your heart. It doesn’t offer up a “new” or “restored” Orson Welles film, because there never was a film. It doesn’t even offer an ersatz Welles film cobbled together out of Welles footage, like the distressing version of Don Quixote recently released in Spain. But what it does provide is indispensable: a cogent account of what happened with the project and enough of the original footage to allow one to speculate at some length about what might have been.

The film should leave you feeling vaguely unsatisfied; anything else would have been a lie. And if it presents a quandary, it’s neither the first nor the last one posed by Welles’s unruly career — a career that constantly brings up the question of what a work or an oeuvre actually is.

***

Among the many film projects Welles had in development just after the release of Citizen Kane, in May 1941, were one about Landru, a 20th-century French Bluebeard (a project written for and eventually purchased by Charlie Chaplin, who converted it into Monsieur Verdoux); a life of Jesus set in America at the turn of the century, conceived as “a kind of primitive western”; a political thriller centered around a fascistic news commentator; adaptations of The Magnificent Ambersons and Journey Into Fear; and an omnibus feature called It’s All True, consisting of four true stories — a history of American jazz, a story by John Fante about his Italian parents meeting in San Francisco, and two stories by documentary filmmaker Robert Flaherty, one about a Mexican boy’s friendship with a bull (“My Friend Bonito”), the other about a boat captain. An anthology format had served Welles well on radio, and he launched a new weekly show around the same principle in the fall; by then, three of his film projects were in production, with Welles serving as writer-director-producer on Ambersons, producer and actor on Journey, and producer on It’s All True. In September Norman Foster began directing “Bonito” in Mexico under Welles’s supervision, and the following month Welles began shooting Ambersons. In December, two weeks after Pearl Harbor, he received a telegram from the coordinator of the federal Inter-American Affairs office asking him to undertake a goodwill mission to Brazil and make a noncommercial film there without salary to promote “hemisphere solidarity,” with RKO studios footing the bill but the government guaranteeing up to $300,000 against potential financial losses. Nelson Rockefeller, a major RKO stockholder, and President Roosevelt, a personal friend of Welles, both urged him to accept; Rockefeller was adamant that Welles arrive in February, in time to shoot the annual Rio carnival.

Welles finally agreed, on condition that he be allowed to finish cutting Ambersons in Rio with his editor, Robert Wise. In early January he recalled Foster from Mexico to begin directing Journey Into Fear, intending to complete “Bonito” himself on his way back from Brazil and incorporate it into a revamped, South American It’s All True. Speeding up both Ambersons and Journey in order to make his deadline, he finished his production work and suspended his radio show by February 1, flew to a briefing with government officials in Washington the next day, and proceeded directly to Miami for a three-day marathon editing of Ambersons with Wise. Then he flew to Rio, where he and his crew immediately began shooting the carnival, in Technicolor and black and white.

Over the next month Welles began to sketch two Brazilian stories to go with “Bonito”: an account of the samba at the carnival, to replace his history of American jazz, and a reenactment of an epic 1,650-mile raft journey taken the previous fall by four impoverished jangadeiros (fishermen) from Fortaleza to Rio to speak to President Vargas about their economic exploitation by the owners of their fishing rafts, who collected half of their weekly catch. Welles’s celebration of impoverished blacks in both these stories, quite compatible with the emphasis of “Bonito,” raised the hackles of Brazilian government officials and RKO studio executives alike, and some U.S. government officials expressed their displeasure as well. The four jangadeiros may have become national heroes, but their activist leader, Jacare, was considered a communist; the film hardly promised to correspond to the touristic propaganda about Brazil the local dictatorship wanted. When Welles took his Technicolor cameras into the favelas (shantytowns) to trace the origins of samba, he and his crew were ejected from at least one of them at Vargas’s behest. Meanwhile, Welles was commissioning an extraordinary array of research into Brazilian life and culture by a large team of Brazilian (not Hollywood) writers, producing a weighty file of ambitious essays that still exists.

These radical aspects of the project, elided or minimized in most previous North American accounts of It’s All True — or else distorted by racist innuendo, such as reading Welles’s friendship and collaboration with blacks as simply “partying” or slumming–have never been forgotten in Brazil. Grande Othelo, the star of “The Story of Samba,” whom we also see and hear 50 years later in the documentary, compared Welles to Martin Luther King when he spoke at a Welles conference held at New York University in 1988. And the very fact that such a conference was held became front-page news in a Sao Paulo newspaper.

Things began to go badly for Welles. Not honoring its promise to send an Ambersons rough cut with Wise to Rio, RKO decided to preview the film. A week after the second preview, Jacare drowned in an accident while he and the other three jangadeiros were preparing to restage their triumphant arrival in Rio for the film.

Then things got even worse. Rockefeller left the RKO board of directors, and shortly after studio president George Schaefer — the man who’d first lured Welles to Hollywood, had remained his strongest ally, and had even come up with the title for Citizen Kane — was forced to resign. More than 45 minutes were hacked out of Ambersons by Wise and others, in part to soften some of its harshness, and some scenes were reshot or added. Then Welles’s staff was summarily evicted from the RKO lot, and It’s All True was halted in mid-production.

Before returning to the States, Welles was permitted to shoot, from mid-June to mid-July, a revised “Four Men on a Raft,” without sound and in black and white, on a minimal budget and with a skeletal crew, in Fortaleza, Recife, and Salvador. But when he returned to the U.S., no one would go anywhere near the project.

It would hardly be an exaggeration to say that Welles’s career never fully recovered from RKO’s mutilation and dumping of Ambersons and Journey, its abrupt scuttling of a third picture, and its well-mounted campaign depicting Welles as irresponsible and out of control — a clear attempt to justify its actions. (The following year RKO’s stationery bore the pointed slogan “Showmanship instead of genius.”) Almost three years passed before Welles could direct another picture, and the image of him proffered by RKO has become so well entrenched over the past half century that it’s still repeated in some quarters like a comforting mantra. Critic and biographer Charles Higham devoted two full books, published in 1970 and 1985, to propounding it, and Robert L. Carringer’s The Magnificent Ambersons: A Reconstruction, published this year, argues that nothing could have made Ambersons an artistic success because of Welles’s Oedipal hang-ups and his irrational denials stemming from them. (Speaking of irrational denials, over the course of 307 pages Carringer fails to mention It’s All True once, even in a footnote, and seems to regard the entire Brazilian episode as extraneous to what happened to Ambersons.)

Considering the sacred value we accord the bottom line, we shouldn’t be surprised that some academics (like Carringer) defend RKO’s business sense in eviscerating Ambersons and Journey, though both movies lost piles of money anyway. After all, it was the principle of the thing — the pride and honor of the studio system itself — that was at stake.

This isn’t to argue that Welles had any business sense or even much common sense when it came to ingratiating himself with that system. Three months before the release of Citizen Kane he published an article attacking the functions of most producers, agents, and studio heads, and the implied threat to the system represented by his original Hollywood contract, which granted him almost unlimited control of his pictures, clearly made many in the film industry livid. While he inspired passionate loyalty from most of his staff, one suspects that his business associates, starting with John Houseman, regarded him somewhat more ambivalently. (When he was off in Brazil his business manager was Jack Moss. According to writer-director Cy Endfield — who was working for Moss at the time, and whom I interviewed earlier this year — many of the frantic long cables Welles sent Moss about the reediting of Ambersons went straight into the wastebasket unread.) If Welles’s troubling career carries any lesson, it’s that the same delirious risk taking that led to such unmitigated disasters paid off spectacularly in other situations, including Kane.

The dogged efforts of academics to assign a neat, linear progression to Welles’s oeuvre are frequently misguided, being generally based on what was released rather than what was filmed. When one reads that The Immortal Story (1968) is his first color film, the dazzling, extensive Technicolor footage he shot in Brazil 26 years earlier, some of which we see in It’s All True, is overlooked. Other “experts” acknowledge the Brazilian color footage but assume all of it was devoted to the carnival — a myth that has clung to Welles scholarship so tenaciously that some reviewers of the new documentary have been expressing doubts that the other Technicolor footage briefly visible in It’s All True is Welles’s. (A subtle bias about arty black and white being the only proper medium for showing poverty — a bias reflected in most documentaries and neorealist features of the 40s — may be behind this uncertainty.)

Similarly, many critics — myself included — have cited Othello as Welles’s first independent feature. It probably is; but it might be argued that It’s All True, which started out seven years earlier as a Hollywood feature with full studio resources, wound up independent, at least when Welles was shooting most of “Four Men on a Raft,” and certainly when he was trying to keep the project alive afterward. (In truth, it’s a bit of both; the documentary shows us the Hollywood-ish trickery involved in shooting the men on the boat, but also reveals how crude and improvised such “special effects” had to be.)

***

With the possible exception of Erich von Stroheim, no Hollywood figure better illustrates the incompatibility of art and commerce than Welles. It’s an incompatibility that can easily be overlooked or rationalized if one’s looking at the careers of certain giants during the heyday of the studios — figures such as John Ford, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, and Ernst Lubitsch — but is much harder to ignore today, when the conditions that allowed such careers to flourish no longer exist. (People who cite Citizen Kane as a counterexample tend to minimize the fact that on first release it played only at independent theaters and lost money. It was never previewed and came very close to being destroyed: Louis B. Mayer and other studio executives offered to reimburse RKO for the total cost of the picture if it would burn the negative. If RKO president George Schaefer hadn’t defied the Hollywood community by rejecting the offer, we wouldn’t have the film today.)

Most moviegoers and reviewers would still prefer to ignore this incompatibility because the business couldn’t be run as smoothly if they didn’t, and one of the most popular rationalizations for ignoring the incompatibility of the two is “retrievability.” According to this myth, it doesn’t really matter how many movies are mutilated by producers or distributors, because they can always be “restored” later, on laserdisc or otherwise. But it’s absurd to apply such a myth to Welles. We can’t “restore” Ambersons, because all the cut footage was destroyed by the new RKO management in late 1942, and we can’t “restore” It’s All True because it was never allowed to exist. That’s why the documentary It’s All True needs its awkward subtitle, Based on an Unfinished Film by Orson Welles; without it, the film sounds like a resurrection.

All we now have of the original film are some of the raw materials — those that weren’t dumped into the Pacific Ocean when the space at the studio storage facilities was needed. Not only is most of the carnival footage missing, but also all of the editing Welles did in subsequent years done whenever he was attempting to persuade a studio to resuscitate the project in some form. (At one point he even purchased the footage himself, but was unable to keep up the storage payments.) It’s worth adding that most of the “Bonito” footage appears to have survived as well — though we see only one sequence of it in It’s All True, a lovely depiction of the blessing of young animals in a village church — and all this undeveloped footage will turn to dust if funds for its preservation aren’t made available.

In keeping with Welles’s chameleonlike propensity to change some aspects of his style in every film project, It’s All True is atypical. The pagan Catholicism we glimpse in all three projected episodes can be read in light of Peter Bogdanovich’s recent revelation in This Is Orson Welles that Welles was raised a Catholic — which perhaps also adds a spin to the influence of John Ford’s style on this picture. It’s hard to find other overt examples of Catholicism in Welles’s work. However, the spare expressionist graveyard here is echoed in the Celtic crosses of his Macbeth; some of the heroic, low-angle diagonals look forward to Othello (which used the same gifted cameraman, George Fanto); and the sculpted, spacious sky vistas and cloud formations anticipate those in Don Quixote, which was also improvised and shot silent. (The last two traits suggest the visual styles of Eisenstein and Dovzhenko respectively, but they’re also evident in a good many 30s documentaries.)

The profusion of close-ups here, I should note, is at odds with the mise en scene of both Kane and Ambersons — movies that resort to close-ups rarely, and then only at climactic junctures. Those films, of course, employed professional actors, and Welles liked to joke that he used close-ups only when the actors weren’t good enough; even so, I think Ed Marx’s editing favors them too much, leading to an overall dulling effect. “Four Men on a Raft” also lingers over beautiful images in a way that authentic Welles movies, which are too restlessly busy with their narrative and expository agendas, never do. (To my mind, Marx’s editing most nearly approximates Welles’s during the blessing of the animals in “Bonito.”) Nevertheless, having watched about seven hours of the “Four Men on a Raft” rushes on video a few years ago — much of it devoted to repeated takes of the same shots — I don’t think it can be said that Marx hasn’t respected the material in his editing choices. For the most part, he’s simply allowed it to breathe and exist, and by doing so offers us more of the Welles scrapbook to pore over.

***

The new documentary begins with Welles semihumorously describing a voodoo curse placed on the original It’s All True when RKO closed down the production. (The clip comes from Orson Welles’ Sketch Book, an enjoyable weekly TV show Welles did for the BBC in the spring of 1955 that’s never been broadcast here.) The curse might appear to have lasted well into the early 1990s if one counts the protracted efforts of the late Richard Wilson — Welles’s dedicated key assistant on It’s All True, who worked on most of his stage productions, radio shows, and Hollywood pictures before becoming a filmmaker in his own right — to get this documentary about It’s All True made.

After making a 22-minute trailer in 1986 in an attempt to raise money, Wilson spent the last five years of his life struggling to get this story told on the screen. A rare scholar among filmmakers, Wilson was so scrupulously devoted to accuracy in Wellesian matters that only a few months before he died from cancer, when he was keeping his fatal illness secret from everyone but close friends and family, he spent a good six or seven hours on the phone with me making meticulous corrections and additions to a long account of Welles’s career I was compiling, undoubtedly aware that he would probably never live to see it in print.

Back in 1985 Wilson was joined on the It’s All True project by critic Bill Krohn, the Los Angeles correspondent of Cahiers du Cinema, and two years later by Myron Meisel, a former film critic for the Los Angeles Reader and Chicago Reader. The following year they were joined by the invaluable Catherine Benamou, a Latin American and Caribbean specialist who’s done exhaustive field research with the original participants in It’s All True in Brazil and Mexico (and is preparing a dissertation on the subject) and even speaks the local jangadeiros dialect. Only after Wilson’s death in 1991 did the project finally acquire the funds, from France, needed to complete it.

I doubt that this documentary deliberately set out to be a modernist text. Its mission was to tell the truth — a task that isn’t always as easy as it first might appear — and in the process of honoring this mission became something more complex than a simple news report. (The only textual lapse I’m aware of is a simple gaffe in the opening narration — setting the New York premiere of Citizen Kane in Hollywood.) However keenly we may feel the absence of Welles’s voice narrating and explaining “Four Men on a Raft,” we see this silent footage after half an hour of Welles talking about the film’s subject on all sorts of occasions over many decades: on radio shows of the 40s, TV shows of the 50s and afterward, and even in private, taped conversations with Peter Bogdanovich. In addition, Miguel Ferrer’s narration alerts us to the central facts we need to know about the narrative of “Four Men on a Raft” before we get to it. The subtle effect of this detailed dossier combined with Welles’s voice is to assist us in constructing our own imaginary Welles film out of the key materials available — making this film, like all of Welles’s work, interactive moviegoing.

If Welles had completed It’s All True in 1942 it would have offered both a radical contrast to Ambersons — a look at the poorest segment of society after a sustained look at the wealthiest — and a certain continuity, insofar as Welles’s familiar radio voice would have served as the viewer’s intimate tour guide in both. Because the two Brazilian episodes were essentially shot without scripts, they offer early glimpses of the impromptu shooting methods that characterize many of Welles’s late film essays, such as F for Fake and Filming Othello. They also hark back to a much more dated view of documentary associated with early Robert Flaherty pictures such as Moana, as well as F.W. Murnau’s expressionist South Sea tragedy Tabu, which Flaherty worked on as a writer — a romantic and pre-Marxist view of noble folk (if not noble savages) living in harmony with nature, with no obvious ties to the industrialized society observing and recording them. (You’d never guess from this picture that Fortaleza was and is a bustling resort city.)

The Flaherty mode of restaging real events and inventing others is fully embraced by Welles; one key strain in the narrative — the romance, wedding, and subsequent drowning of a young fisherman in Fortaleza — is purely fictional, though this drowning alludes to the real drowning of Jacare. This approach to actuality is worlds away from the synthesis of archival material, recent interviews, and factual commentary provided by Wilson, Krohn, and Meisel in the preceding half hour, even though it consciously strives to honor and do justice to the same people, and this implicit contrast between articulations of “what’s all true” in 1942 and 1993 is one of the movie’s most valuable history lessons. Equally striking is the sense of separation between what Welles wanted the film to do and how it registers today: the 1942 feature was designed to end euphorically with Technicolor carnival footage recounting the story of samba after the fishermen arrive in Rio, but because of our knowledge of all that happened (or didn’t happen), portions of that euphoric footage at the end of It’s All True can’t provide the same lift.

Much as one can regard the original It’s All True as an independent venture and a studio project, the extensive collaboration of Brazilians on the film makes it qualify to some degree as part of the history of Brazilian cinema. From this standpoint, the academic critic Robert Stam has argued plausibly that Welles managed to anticipate some of the themes, methods, and “social audaciousness” of Cinema Novo (the Brazilian new wave) in the 60s and afterward.

Indeed, one of the most moving aspects of the film is the evidence of how deeply Brazilian participants in the 1942 film and their relatives today revere Welles for the story he was trying to tell about them. “This film is the only inheritance the four fishermen left us,” the grandson of one of the jangadeiros says today, just before “Four Men on a Raft” begins — heart-stopping testimony to a loving trust that has endured for 50 years. It’s no wonder Welles felt inclined to idealize and exalt these people — people who, as the film makes clear, are exploited as badly today as they were then, but who are still uncynical enough to believe that a truthful documentary about their situation might improve their lot.

“Cheap labor,” a skeptical friend of mine scoffed while watching some of the extras in rushes of “Four Men on a Raft” a few years ago. The condescension he found in this footage points to the irreparable damage popular-front attitudes have suffered in our culture since the 30s, when Welles was cutting his teeth on agitprop like Marc Blitzstein’s dated socialist opera The Cradle Will Rock. Yet the faith shown in It’s All True by the Brazilians leads me to question my friend’s cynicism: if we can see “beyond” popular-front optimism today, what is it that’s so much more precious to us? The style of the 40s footage may be dated as hell, but in feeling it corresponds pretty closely to what the jangadeiros are still saying to us — and if it’s the 40s style that keeps us from hearing them, so much the worse for us. This movie, at least, has kept the faith.

December 5, 2020 postscript:

Dear Jonathan (if I may),

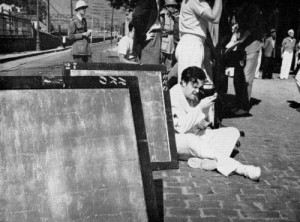

Reading again your wonderful review of the Wilson-Meisel-Krohn It’s All True: Based on an Unfinished Film by Orson Welles, I was struck by the penultimate still, which appears to be from the ‘Four Men on a Raft’ section of Welles’s film (link from your website here). It’s an astonishing composition, and I simply had to find a copy of the photograph for myself! In the process, I discovered that it’s not a still of the film at all, but a shot taken by the photographer Doug Menuez around 2011 (the album is available on his website here). The confusion spreads far and wide, as IMDB and many mainstream and specialist publications have listed or used that shot in connection to the film, and this isn’t hard to explain: its fit with the photographic aesthetic of that section of Welles’s film is absolutely uncanny.

With best wishes,

Emmanuel.

Emmanuel Voyiakis